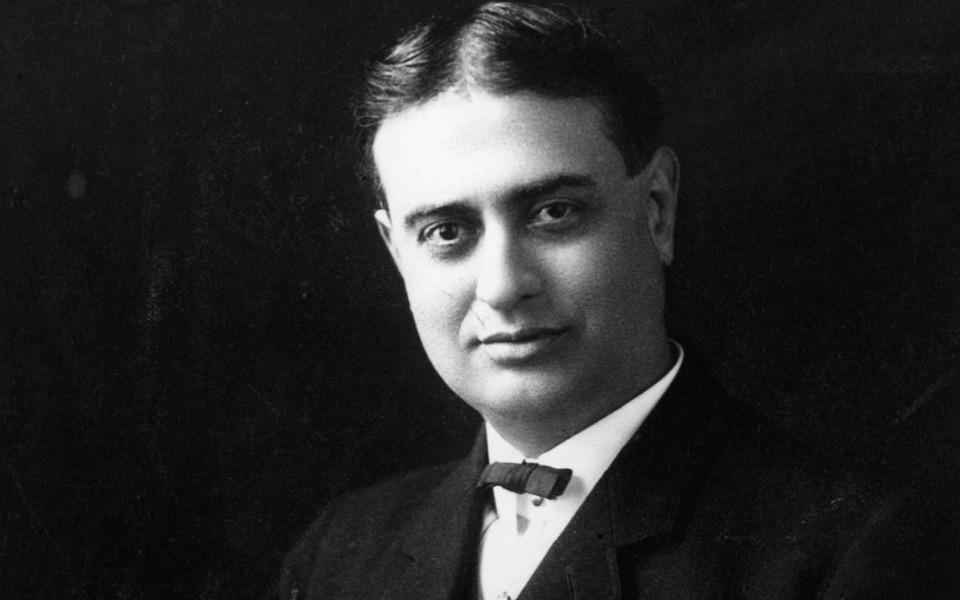

The resourceful Alexandros Pantazis

He emigrated to America at the age of 13. He worked on the Panama Canal and traveled all the way up to Alaska, where he intended to prospect for gold but fell in love instead. He never learned how to write or read English, yet he ran 72 theaters across America armed with nothing but his sharp mind and a small notebook. He was publicly lambasted and his reputation took a beating.

Alexandros Pantazis, aka Alexander Pantages, is one of those larger-than-life personalities of the Greek diaspora that history so often overlooks.

“Within a decade he built a show business empire, with movie theaters that were among the most advanced of that time – some have survived to this day – and assets that would be worth around half a billion dollars today. He was stubborn, hardworking and ruthless; at the same time, he had incredible business acumen and intuition. He was greater than most of his contemporaries in the business yet historians have passed him by,” says Taso Lagos, a professor at the University of Washington who has spent 12 years studying Pantazis for a biography that is expected to be published by McFarland.

Pantazis was born on the Aegean island of Andros around 1867 and sailed off to Cairo with his father when he was around 9 or 10 years old, getting a job at a cafe. America beckoned, however, and a couple of years later he found himself in Panama with a pickax in hand taking part in one of the world’s biggest technical accomplishments. He then moved on to San Francisco, where he worked as a dishwasher, waiter and other odd jobs, including a spell as a boxer.

He set off to the Klondike in 1897 to tap the gold rush and then went to Dawson, also in Canada. Discovering that prospecting was not the job for him, Pantazis took a job at a bar, where he got his first lessons in the world of show business. He went on to set up his own place, headlining vaudeville star Kathleen Rockwell, or Klondike Kate. She soon became his mistress.

Pantazis returned to the US four years later, moving to Seattle, were he decided to get into the movie business. “At the time, cinema was regarded as third-rate entertainment,” says Lagos. “It emerged from the vaudeville scene, which was considered borderline pornographic, and at first only employed immigrants – Greeks, Italian, Bulgarians, Poles and Jews started the cinema and made it one of the most popular forms of art in the country. Pantazis was acquainted with vaudeville from Dawson and was determined to open his own space as soon as he arrived in Seattle.”

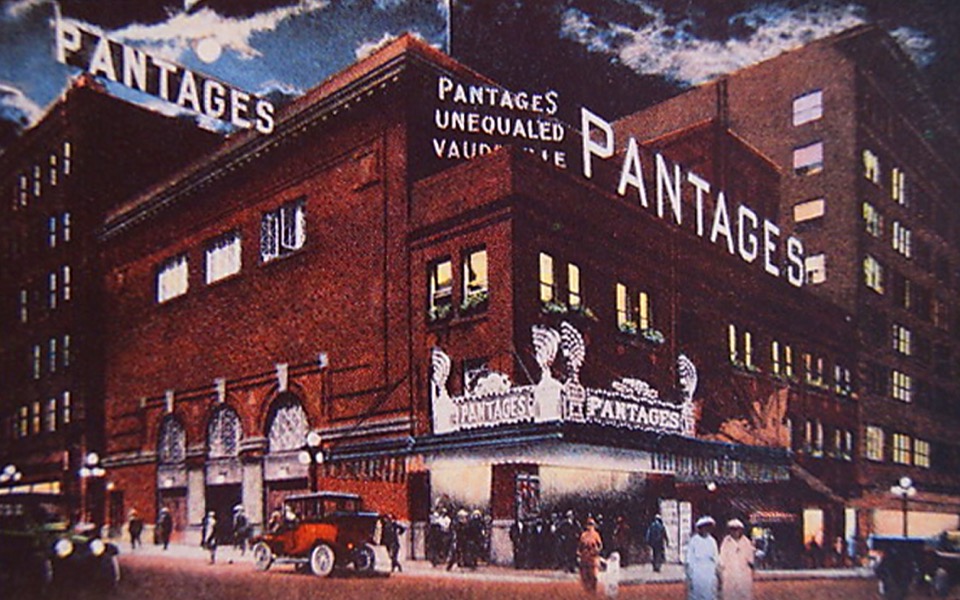

The Crystal was his first theater, to be followed in the next three years by many more in the US and Canada. The theater chain, which he named Pantages, put on vaudeville shows and also screened films, the latest trend in entertainment and one with growing popularity. New heroes such as Charlie Chaplin appeared on his screens, while the Greek businessman was among a handful who encouraged a young Walt Disney to do his thing.

The Pantages theaters were palatial affairs, designed by his friend the Scottish-Jewish architect B. Marcus Priteca to exude an air of luxury, though at an affordable price. He never booked an act or a film without first watching it along with a real audience to gauge its reaction. At the apogee of his career in 1926, Pantazis owned 30 theaters and managed another 42.

“He was a visionary decades before Jeff Bezos and Steve Jobs, showing a true commitment to his customer. That’s why he survived in such a competitive environment. On the other hand, he was a ruthless employer. He’d sign a contract, then cut the artists’ fee by 25 percent and then tell them they could stay or go. Several took him to court,” says Lagos.

But even the mighty can fall – and usually with a louder bump. In 1929, Joseph Kennedy, a businessman, investor, politician and the father of JFK, was in negotiations with Pantazis for the purchase of some his theaters and studios. It appears, however, that the American did not play it straight with the Greek and, according to urban legend, he paid 17-year-old dancer Eunice Pringle $10,000 to accuse Pantazis of rape. The Greek businessman stood trial and was initially found guilty, spending seven months in prison.

Pantazis appealed his sentence and was acquitted in the second trail after his lawyers exposed the holes in the young woman’s story, but the damage was already done. Whether Kennedy was involved or not, what came with the first trial was a deluge of negative publicity, spearheaded by the Los Angeles Examiner, then owned by the king of yellow press, William Randolph Hearst, who later inspired “Citizen Kane.”

“No one can know what happened with any certainty. Personally, the evidence tells me that the rape charge was trumped up. They probably did have relations, but that does not mean the girl did not consent. The problem was that Pantazis already had a reputation for ‘liking them young’ and this is what the press relied on,” says Lagos. “His reputation was destroyed… He was never rid of the rapist stigma even though he changed a lot after his ordeal and became much calmer and approachable.”

Most of Pantazis’s theaters were sold and a few were managed by his two sons. The ingenious Greek entrepreneur died in his sleep in 1936.

Writer and researcher Nikos Theodosiou, the nonprofit organization Mnimes (Memories) and writer Fondas Ladis are currently in the final stages of a book about Greek pioneers in the American film industry. There will of course be an entire chapter dedicated to Alexandros Pantazis.