Untangling the tale of a Jewish WWII orphan in Thessaloniki

Just a few days before the mass deportations of Thessaloniki’s Jews to Nazi concentration camps began in the cold tail-end of winter 1943, many Jewish parents left their children in the care of the Aghios Stylianos Foundling Home for their protection. Unable to bear the separation, most took their children back; but some stayed. One of them was David Barzilay, born on March 4, 10 days before the first death camp train left the northern port city.

What happened to the baby that was declared by the foundling home as being “of unknown parentage” and survived the Holocaust? How many more Jewish families tried to save their children in this way and what kind of life did the youngsters go on to have afterward?

These and other such questions came to social anthropologist Aigli Brouskou’s mind as she studied the Aghios Stylianos archives for her book “Logo tis kriseos sas charizo to pedi mou” (Because of the Crisis I Give You My Child), published by the Scientific Society of Child and Adolescent Care. The answers came later with painstaking research at three official archives, while the evidence pertaining to one particular case turned out to be very revealing: It allowed a name to be erased from the long list of Thessaloniki’s Holocaust victims; shed light on fabricated records; allowed the survivor to rewrite his autobiography; and exposed the complex and often conflicting roles of those who saved lives during the Nazi occupation.

The tangled tale of a baby declared at birth as Dario Massarano, then christened Achilleas Mouratidis and then adopted as David Barzilay (his mother’s surname) was unraveled by three researchers. Brouskou (who did research at the Aghios Stylianos archives), Areti Makri (record manager at the General State Archives) and Aliki Arouh (archive director for the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki) traced his journey from Thessaloniki to his current home in Montreal.

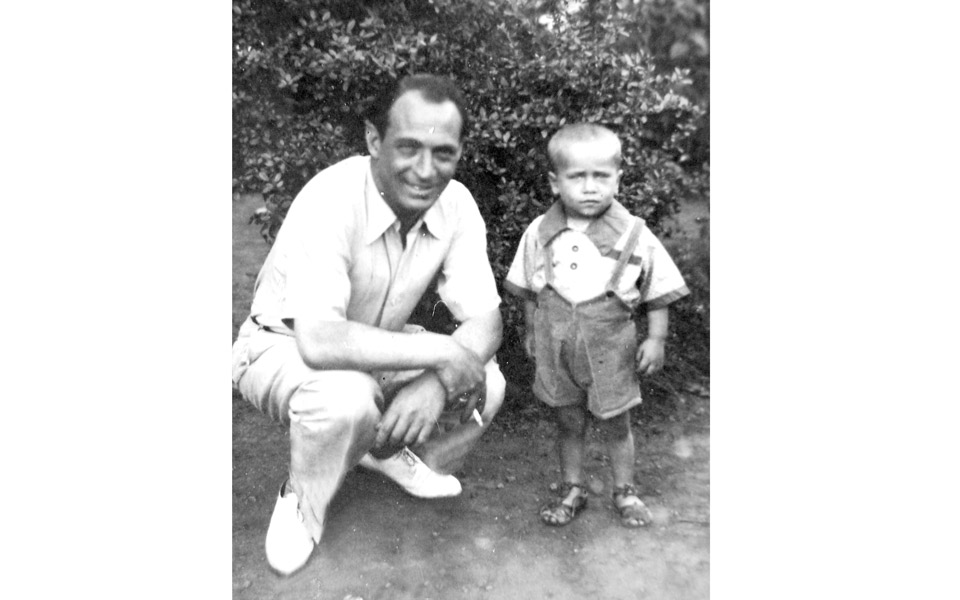

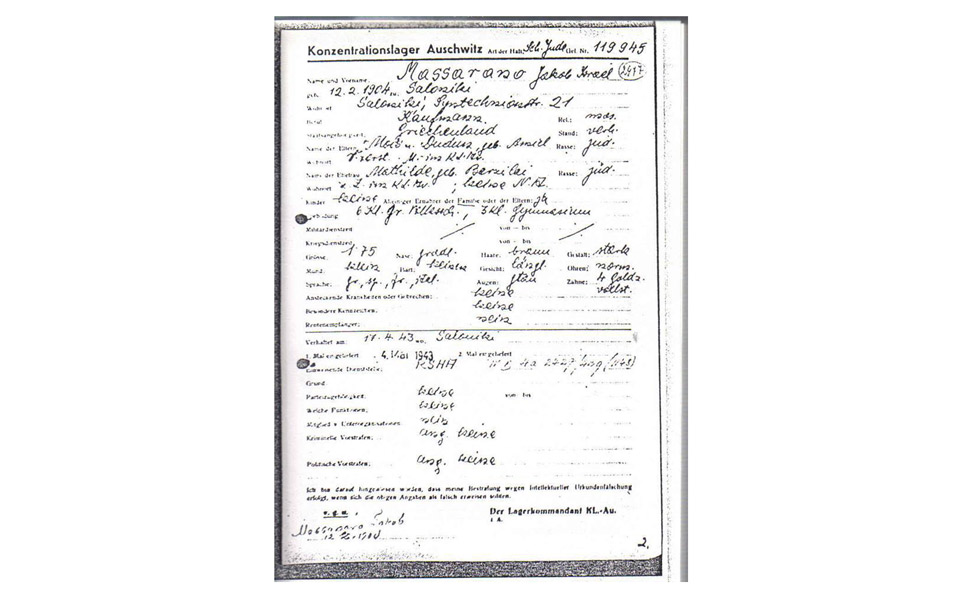

David Barzilay’s birth parents – Jacob, 31, and Mathilda, 20 – were married in Thessaloniki in 1941. In the compulsory registration of the German-occupied city’s Jews in 1943, Jacob Massarano declared a newborn boy, but Auschwitz inmate number 119945 was not accompanied by any child, suggesting the infant had remained in Thessaloniki.

Arouh unearthed a letter from Aghios Stylianos informing the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki that it had four circumcised babies in its care. Brouskou’s research showed that several children were taken into the foundling home in February and March 1943, though most stayed less than a day as their parents had a change of heart.

“We don’t know whether the girls survived. The four boys were all handed over to surviving relatives or sent by the Jewish orphanage in Athens to Palestine in 1946,” says Brouskou.

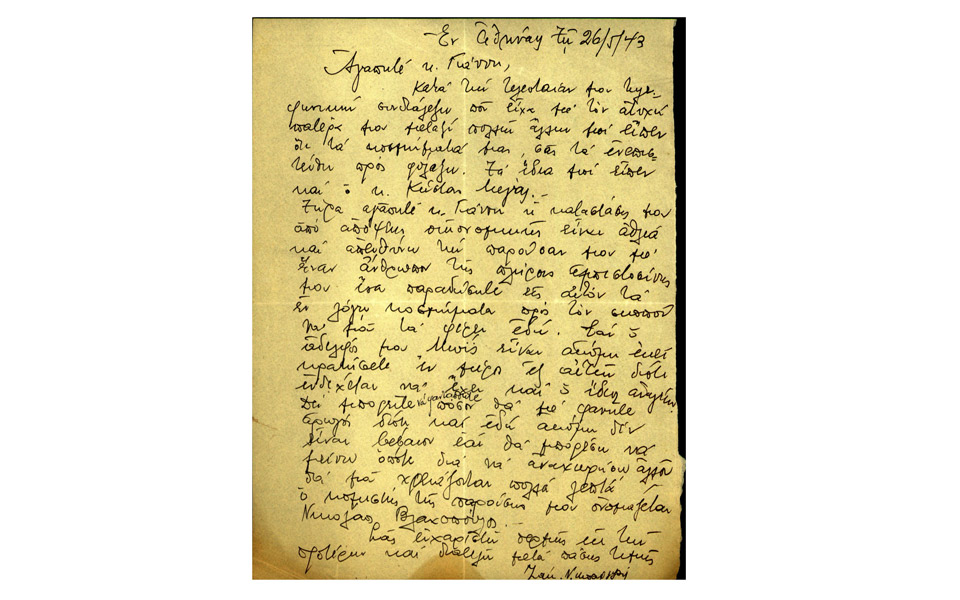

The second key piece of evidence, found by Makri, was a 1958 document in which maternal uncle Richard Barzilay, a resident of Caracas in Venezuela, asked notary Ioannis Papias for a sworn statement from Thessaloniki lawyer Ioannis Stathakis explaining what had happened to the Massarano baby. Stathakis declared that on March 16, 1943, a few days before being deported to Poland, the Massarano couple came to his home and asked that he become the baby’s guardian. The lawyer balked at the request and enlisted the help of a high-ranking police officer to have the child committed to the care of Aghios Stylianos. A fake birth certificate was issued, the child was baptized Achilleas and the public records officer assigned him the surname Mouratidis. Despite the 70 percent mortality rate at the time – due to epidemics, medicine shortages and starvation – the child survived the war. This may have been thanks to the intervention of the lawyer, who had an acquaintance working at the foundling home and asked her to pay special attention to the baby.

Another letter from Stathakis’s archive is also signed by a Barzilay and suggests that the lawyer had been given jewelry by the family for safekeeping.

“The letter was extremely important because it proves, on the one hand, the bond of trust between the Barzilay family and the lawyer and, on the other, the complex roles some people played during the occupation,” says Makri. Stathakis, she explains, was accused in 1945 of being a Nazi collaborator and was said to have invited the feared German officer Max Merten to his daughter’s wedding. Stathakis was later cleared but his son-in-law was convicted as a collaborator.

The evidence showed that the baby Dario or David Massarano had survived. “Until we started the coordinated research, Dario was another name on the long list of Holocaust victims. As the pieces came together, I was wildly delighted to scratch Dario’s name off it,” says Arouh.

Their efforts then turned to locating the survivor. A combination of lucky coincidence and solid leads helped them find his surname and they discovered from the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive – now available from the central library of Thessaloniki’s Aristotle University – that the child had been adopted and named David Barzilay.

“There we found the oral and written testimony of the man we were looking for, telling the part of his story that we knew nothing about until then,” says Makri. Social media then pointed them directly to the object of their quest and a series of conversations filled in the remaining blanks.

The researchers learned that after Thessaloniki was liberated in August 1945, his maternal uncle, Jacques Barzilay, came to Thessaloniki from Athens and claimed the child from Aghios Stylianos with the help of the lawyer Stathakis. The child was then sent from Athens to Tel Aviv. He was adopted by his other uncle, Richard Barzilay – and like thousands of other Greek Jews, spent some time in a British-run camp in Cyprus until he went to Israel, then spent a few years in a kibbutz and – following his uncles – went on to live in Venezuela, France, Canada and Manchester, England, where he graduated from university and did postgraduate studies in physics. At the age of 25, in 1968, he moved to Montreal. There, a family friend, a Jew from Thessaloniki, told him his own story.

“David belongs both to the first and second generations of survivors,” says Brouskou. “For years, the secret of his adoption kept him away from this knowledge. The truth brought him immense relief and gave his life meaning.”

“How did you feel when you found out the truth?” the researchers asked him. “Incredible relief,” he answered. “And how about in learning that your parents died at Auschwitz?” “Incredible relief,” he repeated.

The truth was liberating, because, until then, he had to grapple with sifting through silences, facts and lies to help him comprehend his history. The evidence from the archives allowed him to rewrite his autobiography.

“His narrative in turn showed how ‘official’ records are fabricated,” says Brouskou.

Arouh has been helping David Barzilay draw up his family tree over the past few years. He is also writing a family history, starting with the birth of his grandfather, Natan Barzilay, in Thessaloniki in 1879, up to his own marriage in Montreal in 1979 to Sandra Zelikovick, the daughter of Holocaust survivors.

He is to visit Thessaloniki on the weekend of September 17-18, where the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki will be holding a special event in his honor.