Returning to crisis-wracked Greece

On a Sunday morning while most of the city is still fast asleep, Manos Kapetanakis sets off in his 12-year-old Ford Fiesta to his job as a thoracic surgeon at the Attikon Hospital in Haidari, western Athens. If, when he was first starting out in his career, someone had told him that after years of studying and working abroad, this is where he’d be, he would have laughed in their face.

“It was strange coming back home in 2011, during a period of deep crisis,” says Kapetanakis. “My mother would tell me on the phone: ‘What are you going to do here in Greece, son? Everything is gone here, destroyed.’”

Unlike the majority of other doctors who graduated in Greece in his field, opted for a career abroad and never returned, he decided to come back. “I came at a difficult time. Flight is the prevalent trend,” he says.

More than 130,000 Greek university graduates have left the country in the last five years, according to a study, “Emigration from Greece during the crisis,” funded by the London School of Economics. The same data also show that 40 percent of Greek emigres after 2010 have either master’s degrees or doctorates, or are medical or engineering graduates.

“Many of those who leave are basically chased out of the country because it’s very difficult to find work here,” says Lois Labrianidis, a professor of economic geography at the University of Macedonia and scientific supervisor of the study.

However, going against the so-called brain drain trend, some highly skilled graduates choose to return.

“The gains are without doubt twofold. They come back having lived and worked in a different environment that has helped them mature,” says Labrianidis, who as general secretary of strategic and private investment at the Greek Ministry of Finance for the past few months has been seeking ways to attract educated and skilled Greeks from abroad.

Lois Labrianidis is the general secretary of strategic and private investment at the Greek Ministry of Finance.

He says that the government is examining new development legislation to implement a scheme through which employers taking on specialized professionals can be granted privileges and to enhance the creation of research centers. Meanwhile, it is also exploring ways to utilize those who opt to remain abroad by facilitating partnerships in Greece.

Three young degree-holders who returned to Greece from the UK and US explain to Kathimerini why, despite the uncertainty, sluggish professional mobility and low wages compared to their jobs abroad, they decided to make the trip home.

Manos Kapetanakis spent more than two decades abroad. At the age of 14 his family left Hania on Crete for the US. He studied marine biology and then pursued medicine at the George Washington University. After a brief hiatus to complete his military service in Greece, during which he worked at the Onassis Cardiac Surgery Center, he did a postgraduate degree in surgery at Imperial College in London. He remained in London for his specialization and then decided to return to Greece in 2011, when an opening in his field opened up in Athens. Until then, there were no opportunities, he says.

“I had been considering making the transition later, around the age of 50, when I would have more experience. But nostalgia was eating away at me. I had a big house and a good salary, but I would leave in the mornings under an overcast sky and cold drizzle that seeped into my bones, and return in the dark of night to an empty home.”

Day-to-day life in Greece has proved a challenge. He was hired as a specialist at the Attikon and helped assistant professor of medicine Periklis Tomos set up the hospital’s thoracic surgery clinic from scratch. The clinic needed four residents to function properly for quite some time and Kapetanakis had to fill in because of staff shortages. In under nine months, he and Tomos have conducted over 90 surgeries and demand just keeps growing.

However, according to the 39-year-old, the experience he is gaining working beside the clinic chief – whom he calls his teacher – is amply rewarding. “The knowledge I’m receiving is similar to that I would get abroad but I have gained so much in training,” Kapetanakis says.

His decision to return to Greece also took a toll on his earnings. In London he was earning 4,500 to 5,000 euros a month while now his salary for 70-hour weeks and seven emergency shifts a month comes to 1,600 euros. He has received several tempting job offers from the UK, but after discussing them with his wife decided to turn them down.

“A large percentage of doctors leave as a matter of survival. I don’t blame them. I might have done the same if I were at a different clinic,” he says. “I felt that I had to give the new clinic a chance. It is worth staying in Greece to build something new, something different, to put up a fight.”

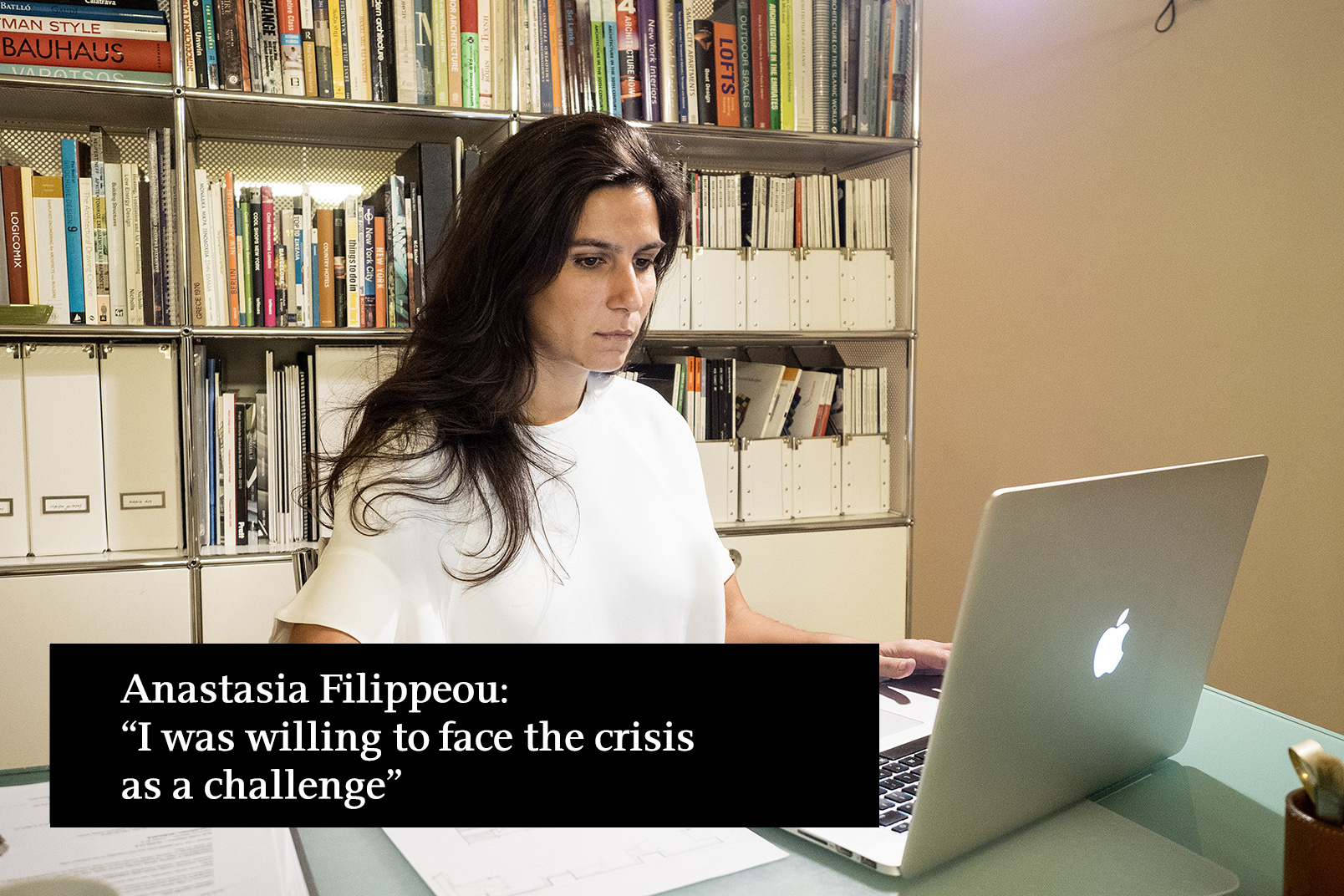

“In total, I have spent more years abroad than in Greece and I never took it for granted that I would return,” says 32-year-old architect Anastasia Filippeou.

She spent most of her childhood in Brussels, then went to the University of Bath in the UK and from there the Polytechnic University of Catalonia in Barcelona. She came back to Greece for a few years and worked at a construction company but then left again to do her second postgraduate degree at the Pratt Institute in New York.

“I imagined myself staying in the United States. I felt from my academic career that capable people get ahead on their own merit,” Filippeou says.

In 2013, however, she saw a window of opportunity opening up in Greece despite the crisis when she started receiving requests from Greeks living abroad who were interested in investing in real estate in Athens and the Greek islands.

“They wanted to take advantage of the sliding prices and wanted me to look into finding them properties and in some cases renovating them or in building new ones,” she says.

In the two years since then, she has renovated homes and shops, worked on studies for foreign projects and had a taste of the difficulties of working in Greece. In the summer, for example, the plug was pulled on one project because of the capital controls introduced by the leftist-led government that limited deposit withdrawals in order to stave off a total collapse of the banking system, and her clients became skittish because of developments.

Other investors from abroad who were weighing their options decided it was not a good time to become active in Greece.

“Returning certainly entails risk. The difficulty does not just lie in the uncertainty of being self-employed but also in the general instability, political and economic, that a young professional cannot predict,” says Filippeou. “But I was willing to face the crisis, not as bad luck but as a challenge, as an opportunity for our generation to do things better.”

Filippeou still maintains her foreign contacts and younger architects often ask her whether there’s a future in Greece for them. “I am bothered by the idea that good minds stay away and can only do well elsewhere,” she says. “Motives need to be given to people from all fields to return and bring back the knowledge they have gained.”

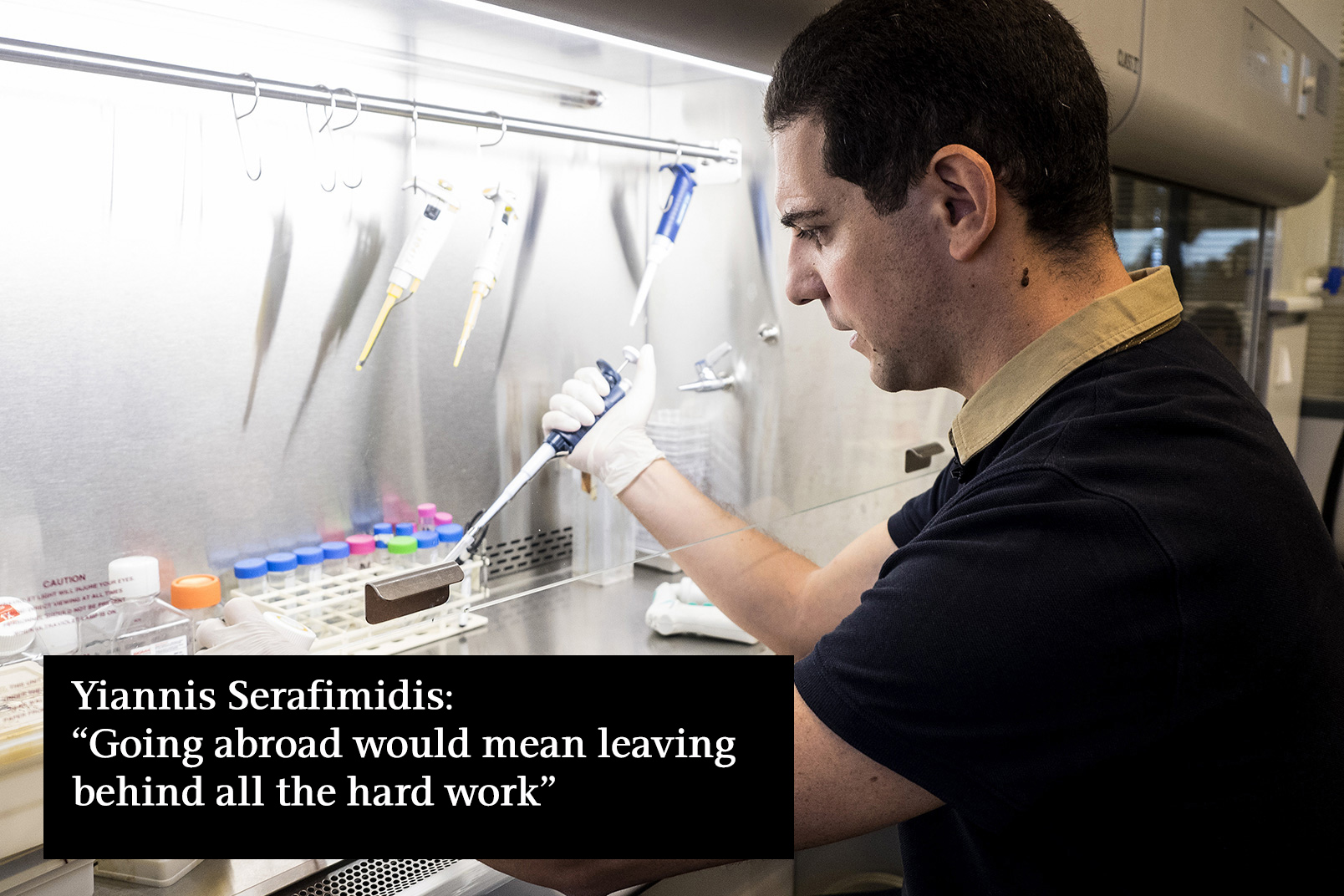

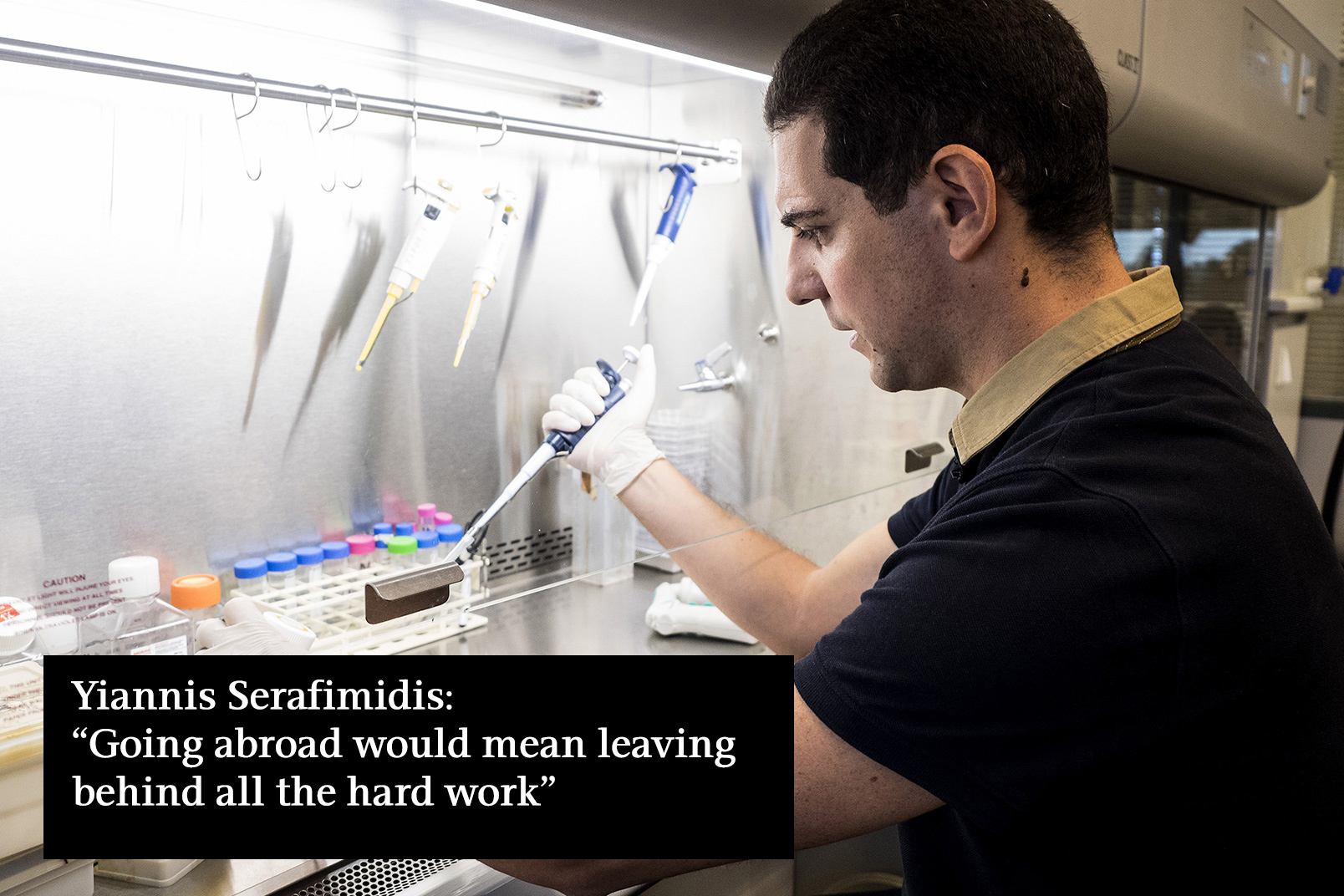

Behind the Sotiria Hospital in a wooden area in northern Athens are the premises of the Athens Academy’s Foundation of Medical and Biological Research. In one these labs, Yiannis Serafimidis spends his days bent over a microscope. He returned to Greece before the start of the crisis and stayed even though he had many opportunities to leave.

“The easiest thing would have been to stay abroad,” he says. “The different thing was returning.”

Serafimidis began his studies in biochemistry at King’s College London at a time when no such course was available in Greece. He earned his doctorate in developmental biology at the University of Cambridge and returned to Greece in 2005 to do his military service. A job opened up at the foundation straight after, and today he is involved in research concerning the pancreas. The aim of the study, which is funded from abroad, is to produce an inexhaustible source of B cells to cure diabetes.

“The reasons I stayed have nothing to do with Greece’s sun and sea, nor with the fact that I couldn’t live without my family and friends,” says Serafimidis. “The only criterion was a scientific environment in which I could conduct cutting-edge research, as I had become accustomed to abroad, on a project that would interest me and would provide me with opportunities.”

Had he continued his career abroad, it is likely that today he would have his own lab and research team like some of his peers from Cambridge. In Greece, career evolution in the arena of research is slow going. “I don’t regret it. I am satisfied with what I’m doing, even if training takes more time,” says the 37-year-old biologist.

Every so often, the expiration of European funding programs and the risk that research programs may be shut down makes young scientists more likely to seek jobs abroad. “How we will bring them back is a purely economic issue,” says Serafimidis. “It has to do with the state funds that are available for research.”

Two-and-a-half years ago he was presented with the opportunity to follow his research supervisor to Dresden, but he decided to stay in Athens and work with him from here. “Basically I have invested in this job. We have the reactors we need and set up the techniques we need. Going abroad would mean having to leave behind all the hard work that has been done so far.”