A rebetiko sensation with a laika heart

Book chronicles the life and career of singer Apostolos Nikolaidis, who left Greece to make it big in the US and Canada

Apostolos Nikolaidis started working in construction at the age of 13, singing as he climbed the scaffolding. “Give us another song,” the other workmen would shout when he stopped. As a teenager in Thessaloniki, he sang along to the bouzouki played by other boys in the neighborhood, before sneaking off to Athens with dreams of becoming a professional singer. He got his first gig at a bouzouki joint in 1959 and an audition for Columbia Records three years later, where he performed in front of his icon, Stelios Kazantzidis. He made an immediate impression, but when he mentioned that he hailed from Pontus, too, Kazantizidis invited him to perform at the venue he was playing that summer in the southern Athens suburb of Moschato. The place filled up with fans waiting to hear Kazantzidis; soon they were also coming for Nikolaidis.

He worked with many of the Greek greats in the years that followed but was disappointed by the record companies and eventually left for Montreal in 1968. The plan to try his luck abroad for three months turned into 25 years, his daughter, Maria Nikolaidis tells Kathimerini during one of her recent trips to Greece, speaking with great love for her father, who died in 1999 at the age of 61.

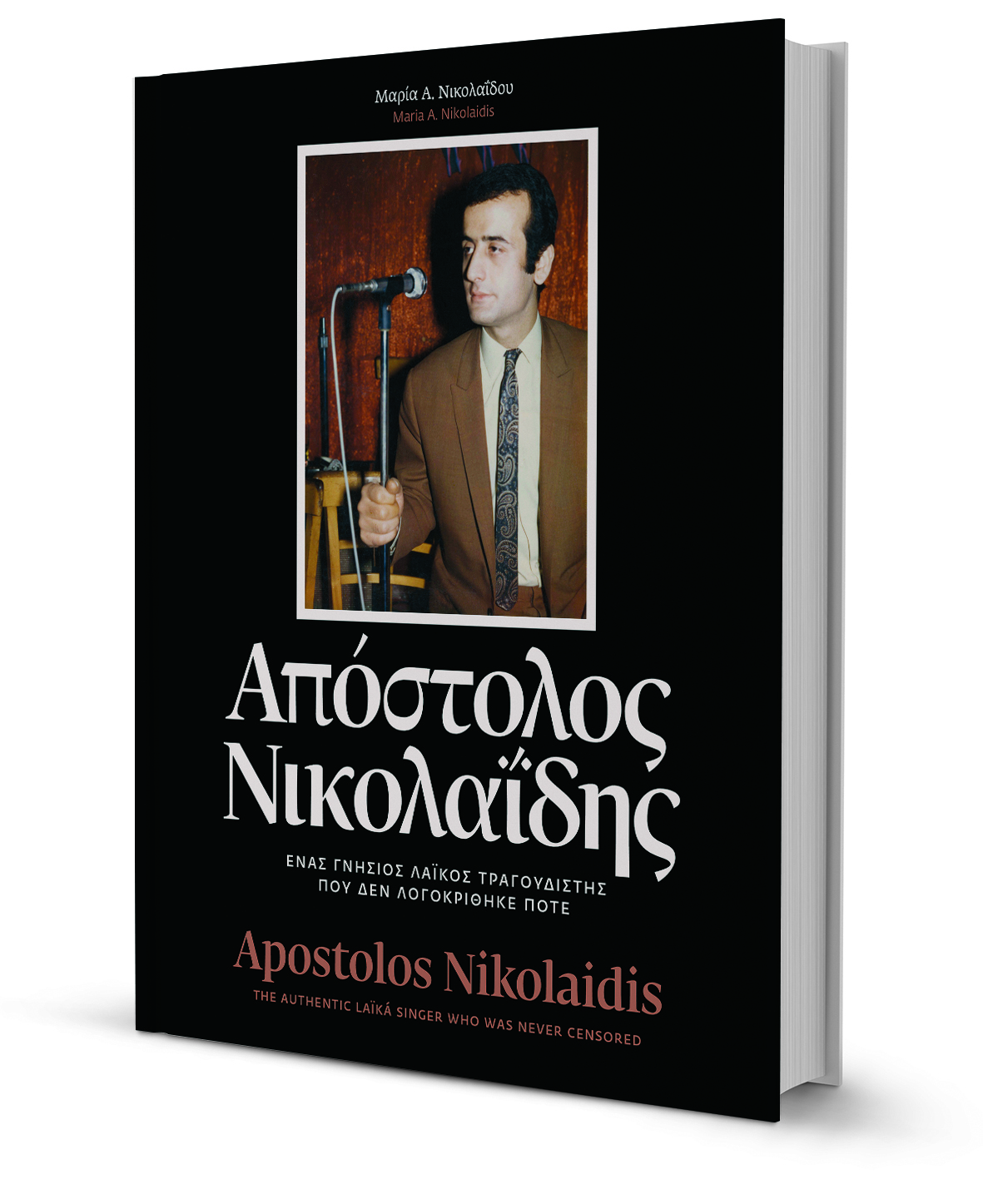

That love is more than apparent in her book, in English and Greek, “Apostolos Nikolaidis: The Authentic Laika Singer Who Was Never Censored,” a rewarding biography with a wealth of testimonies, documentation, photographs and research on his life and a career crowned by incredible recognition in the United States after he recorded the “forbidden” rebetika. “I wanted it to be a grand production, something readers could enjoy and also get all sorts of information from,” says Maria Nikolaidis.

An award-winning designer, creative director and educator with more than 25 years in the graphic design and visual communication business in New York, it took her a decade to write the book. The family archive was incredibly rich thanks to her mother, who kept every publication, but also her father, who added captions to all of his photographs. “The story jumped out from the family archive.”

What kind of man was Apostolos Nikolaidis? “He got the label of a tough-guy ‘rebeti’ who delivered the so-called ‘hasiklidika’ the proper way, and that bothered him, because he regarded himself as a laika singer,” says Maria Nikolaidis, distinguishing between two important genres of Greek music: rebetiko, an “underground” genre that was rife with references to drugs and a dissipated lifestyle, and the more popular laika. “He didn’t accept the label of rebeti. It had negative overtones for the old-timers, you know. A rebeti was a guy with no job, who spent his days hanging around kafeneios.”

Banned songs

‘He got the label of a tough-guy “rebeti” who delivered the so-called “hasiklidika” the proper way, and that bothered him’

Nevertheless, Apostolos Nikolaidis’ reputation took off when, in 1973, he recorded the album of rebetika songs that had been banned in Greece by the 1967-1974 military dictatorship, “Otan Kapnizei o Loulas” (When the Pipe is Smoking), with NINA records. The album also earned him recognition in his native Greece.

“We returned in 1981 so my sister Anastasia and I could go to school here and left again in 1988 to go to university in the US. The second time my dad came to Greece was in late 1994, but he was cheated and became disappointed. He was also disappointed because he recorded an album of love songs that he really believed in, ‘Den Chreiazonte Logia,’ and it didn’t do well. He didn’t want the label of a rebeti who sang hasiklidika to stick. But he had become a cult figure in Greece.”

The country had changed a lot by 1994; most of the old live music venues were gone as people preferred party bouzouki music and dancing on tables, though interest in Apostolos Nikolaidis was revived thanks to a TV series on Greek music by journalist Panos Geramanis.

His greatest fans, however, were the Greeks of the diaspora in the US, Canada and Australia. “Otan Kapnizei o Loulas” contained songs – as the title suggests, featuring drugs, and marijuana in particular – by Giorgos Mitsakis, Vassilis Tsitsanis, Markos Vamvakaris and other legends of the rebetiko genre. At a time when most singers were doing covers of light laika ballads from the 50s and 60s, he tapped into this experience with the legends earlier in his career. “He had learned how these pieces had to be performed.” His reputation soon traveled from America to Greece. “The songs were played on the Greek-American radio, while the album was smuggled into Greece as presents for friends and relatives by diaspora Greeks.”

Maria Nikolaidis’ book also offers insights into what the Greeks of the US and Canada did for entertainment, describing the clubs in Greektown in Chicago and on Manhattan’s Eighth Avenue. They were regarded as “Middle Eastern” nightclubs or cabarets and they started gaining popularity in the 1950s, she explains. “These clubs were a new type of musical and cultural phenomenon in the US, venues that offered constant entertainment with musicians and dancers of many different nationalities that took advantage of elements of orientalism – especially the imagery and symbols – in order to promote an alluring and exotic subculture,” says the writer.

The first of these “Middle Eastern” nightclubs was Zahra in Boston, which opened in 1952. A decade later, the huge success of the films “Never on Sunday” and “Zorba the Greek” had sparked global interest in Greek music, so most of these nightclubs in New York started adding Greek musicians and singers to their rosters.

‘Exotic’ Astoria

In 1977, The New York Times described the ‘Greek’ neighborhood of Astoria in New York as an “exotic city within a city,” “alive with Greek nightclubs, restaurants, tavernas, coffeehouses and exotic groceries.” Many clubs and music stores only featured Greek music and the singer was a favorite in the community. “He was ‘our Apostolis’ to the diaspora Greeks,” says Maria Nikolaidis. Indeed, there are anecdotes of Apostolos Nikolaidis getting showered with dollar bills, flowers and smashed plates. “We only heard about all this from our mother because we weren’t allowed to go to the clubs where our father sang. I also heard that the smashed plates would go all the way up to his knees.”

None of those New York clubs is around anymore, she adds. “The last to go was the Grecian Cave. The younger generation prefers concerts. The idea of sitting at a table to listen to live music is something that would appeal to their parents.”

What kind of music did Apostolos Nikolaidis listen to when he was relaxing? “Kazantzidis; he was a huge fan. He loved [Grigoris] Bithikotsis, [Panos] Gavalas and [Nikos] Gounaris. But he also listened to Elvis, Tina Turner, Tom Jones, Gipsy Kings and even Talking Heads. He may have been ‘tough,’ but he was open-minded,” says his daughter, laughing.