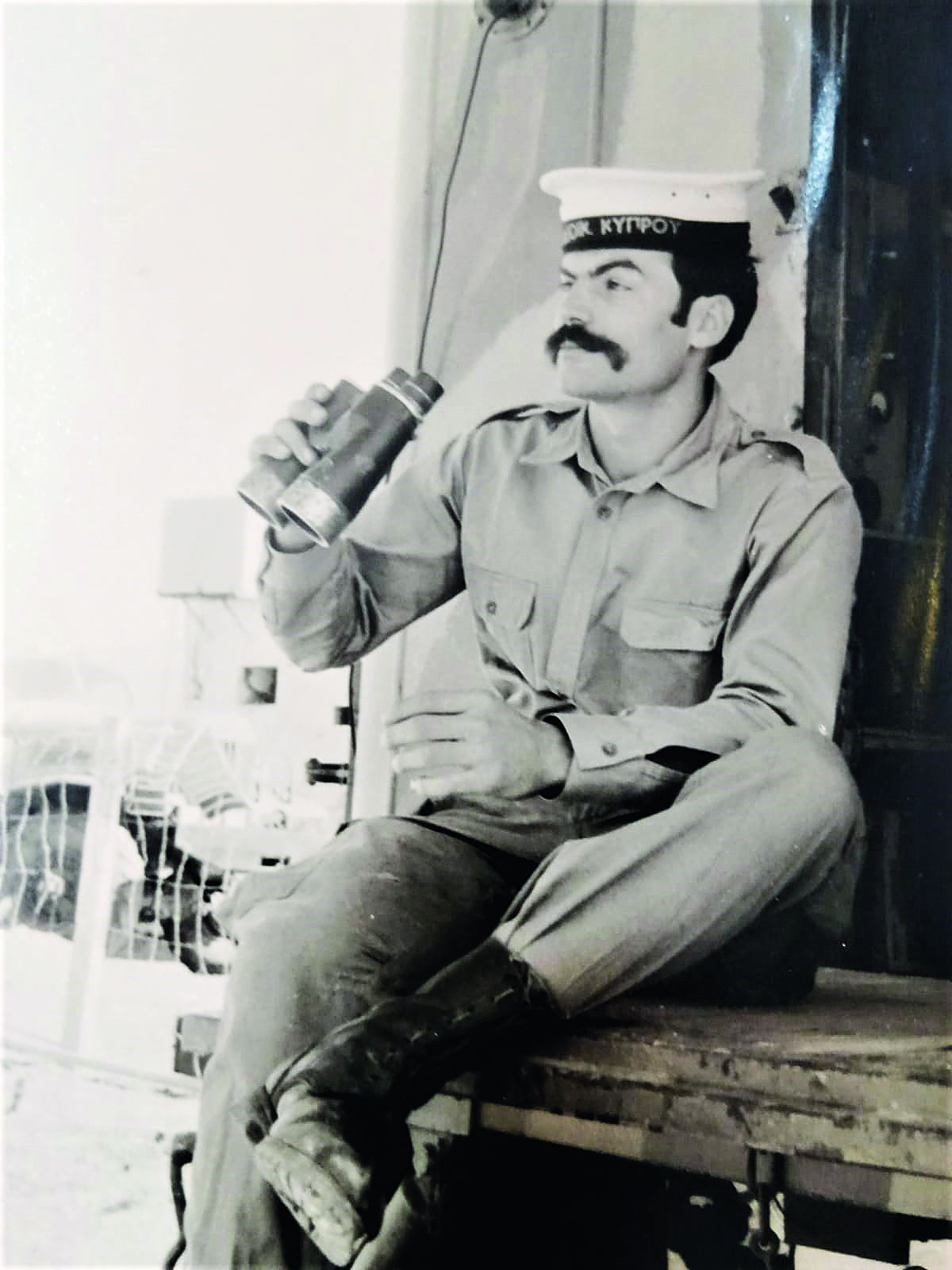

I spotted the Turkish forces closing in on Cyprus on the radar

Ωeteran sailor of the Hellenic Navy speaks of the hours leading up to the occupation in 1974

Forty-nine years after the tragic invasion of Cyprus, Kathimerini tracked down Giorgos Kremastoulis, a veteran sailor of the Hellenic Navy now residing in San Luis Potosi, Mexico. On July 19, 1974, at 8.30 p.m., one day before the invasion, Kremastoulis, working as a radar operator, detected the movements of the Turkish amphibious forces.

In a moving testimony, he shares his firsthand experiences and recounts events from the front line. He vividly describes the emotional moments he shared with his comrades and expresses regret that despite providing timely information about the Turkish movements, the Navy leadership remained inactive. In his poignant account, Kremastoulis describes the betrayal he experienced, both from the Greek forces who failed to arrive on time and from a person he believed to be a fellow soldier but who turned out to be a Turkish collaborator.

“In 1974, after completing basic training in the Navy, I was assigned to the destroyer Ierax. There were 160 of us, sleeping in close proximity. I remember that every month, the destroyer would make a stop at an island in the Aegean Sea as part of our defensive duties. On the ship, I served as a radar operator (surface surveillance radar) and the captain’s secretary. One day, we received a letter stating that they were seeking radar operators to go to Norfolk and bring in new ships. Two days later, another notice came seeking volunteers for surface surveillance radar duty in Cyprus. Eager to leave the ship, I signed up. The following day, I received a message from the [Ministry of National Defense in Athens] to report to headquarters, and the captain said to me: ‘Hey, my boy, what have you done? Do you know where you’re going?’ I replied, ‘Of course I do; it’s Cyprus!’ I departed and headed to Cyprus.

“In Cyprus, there were four early warning stations: A, Bravo, G, which stands for Gali, and D, which stands for Doxa. I was stationed at Doxa. We were located in the northern part of Cyprus. In our unit, there were 12 individuals: one master chief petty officer, one ensign named Manolis, and the rest of us. The radar equipment was mobile, like a truck, a Canadian model from 1943, with a 25-centimeter screen inside. The radar’s function was to emit electromagnetic waves that would hit the target, bounce back, and display as blips on the screen. My role was to receive the signals and transmit the coordinates of the ships via radio. These coordinates were received by the Naval Headquarters of Cyprus, where Rear Admiral Georgios Papagiannis served as the commander. This process was carried out on a daily basis.

“On July 15, we learned about the coup on the radio. We assumed a passive position. The village below us was filled with supporters of [President] Makarios and nationalists. Our radar was positioned on the mountain, and we had placed anti-aircraft guns at the four corners. Consequently, we barricaded ourselves inside, refraining from venturing out even for water, while the villagers refrained from approaching due to fear of our anti-aircraft guns.”

The coup at the Presidential Palace and Archbishop Makarios’ escape set off a chain of events that ultimately led to the Turkish invasion and the division of Cyprus. Kremastoulis recalls that when Makarios left, he had a suspicion that the Turks might invade. “It was on my mind, but no one said it. Everyone was saying not to take action because it was NATO exercises and not to strike unless we were struck. Those words made me feel betrayed. They were spoken both before and during the invasion.

‘Everyone was saying not to take action because it was NATO exercises and not to strike unless we were struck’

“When the Turkish ships departed from Mersin towards Cyprus, I immediately spotted the amphibious vessels and began reporting it, but they kept telling me: ‘It’s nothing. It’s NATO exercises.’ I saw the ships at 8.30 p.m. on July 19. I observed the targets on the radar, which were stuck within Turkish territory, and after half an hour, I noticed those blips moving and descending. That’s when I realized something was happening, and I started providing reports every half an hour.

“After nine hours, at 5 a.m. on July 20, the amphibious vessels arrived. The Turkish ships were in a U-shaped formation, about 5 miles off the coast of Cyprus, and that’s where I saw our commander, Papagiannis, who was the first to realize the mistake, sending the torpedo boats from Kyrenia to face the convoy. However, those were torpedo boats from 1942, Russian ones [a T-1 and a T-3), and they lacked spare parts. One of them [the T-3] approached near the U-formation and disappeared. Later, I learned that the anti-aircraft system on the boat malfunctioned, and [enemy] planes sank [the ship]. As for the second vessel [the T-1], when they attacked it, it was still close to the shore, so they managed to turn around and reach land.

“On a neighboring mountain, there was an Air Force radar station. They lacked anti-aircraft guns, and through my binoculars I could see Turkish planes passing by and bombing them. The flames rose up to 100 meters. I immediately reported it to headquarters, stating, “Two Turkish planes are destroying the aviation radar in Kormakitis, and now they’re coming for us.’ The deputy commander told me: ‘Don’t strike them unless they strike you. Don’t attack unless you’re attacked. It’s NATO exercises.’ But by the time he finished speaking, the planes had drawn closer and attempted to strike us. Luckily, we had anti-aircraft guns, and the Turks didn’t approach immediately. They bombed us on July 21.

“We were the only Navy station where all the men survived. The other stations, A, Bravo and Gali, disappeared. The Turks took over Kyrenia, which served as the base for the torpedo boats, as well as Famagusta. Limassol had nothing, and they abandoned the radar in Ayia Napa and left. We were the only ones remaining on the Doxa radar. We were the final unit of the Navy.

“On July 21, we left our post when our anti-aircraft guns could no longer hold on. I had grown accustomed to the noises, but suddenly I heard every cannon stop firing. So I raised my head out of the radar cabin and realized that everything had come to a standstill, except for the southern anti-aircraft gun. I stepped out and entered the trench. The gunner continued firing with the Browning [machine gun], but even that eventually ceased. Then the planes arrived, dropped their bombs, and we embraced one another. We hunkered down, and all I could think about was my mother and the Panagia [Virgin Mary]. A bomb fell about 30 meters away; it was a napalm bomb, and the soil covered us while the flames from the napalm bomb rose above. The earth saved us.

“Afterwards, we left. There was a forest 500 meters away, and Manolis said to me, ‘Let’s all gather there.’ He handed me his pistol and said, ‘Go and burn all the documents.’ When I arrived, I took a canister, soaked the documents in gasoline, and set them on fire. Silence spread throughout the area. Then we got into the Land Rover and the ensign’s Mini Cooper and drove off to escape from the Turkish lines. We were in the last village in the north of Kormakitis, in Livera.

“We were a group of 12, but only 11 of us made it out. One person [Kremastoulis did not want their identity to be published] betrayed us. He knew more than the rest of us. One day before the invasion, when there were still no signs of Turkish movement, he took an AK-47 that we had at the station, got into a car, and shouted at us: ‘You fools! You stay back and die.’ Unfortunately, there was an Ephialtes among us.

“Then we arrived at the infantry camp, and the lieutenant colonel said to us: ‘How nice of you to come! We need reinforcements because we will attack Hill 503.’ However, we were Navy, not infantry. So the ensign stepped forward and said: ‘Very well, Colonel. We’ll come and give you an answer shortly.’ We left his office and had to go to Naval Headquarters. The locals told us, ‘We can get you away from the Turkish lines, but we mustn’t turn on the lights.’ So I sat on the car hood and signaled ‘left-right.’ The road was filled with bomb craters. We arrived outside Nicosia in a forest where there were tents, and that was Naval Headquarters.

“Afterwards, we stayed at headquarters for two or three days. A ceasefire was declared, and we returned to the radar to provide information. The Turkish forces had not yet reached our radar station. When the second wave of hostilities (Attila II) began, three Turkish destroyers approached us. Suddenly, they turned their cannons towards us and aimed at us. We started shaking with fear. However, after some time, they returned to their positions and departed for Paphos. It was during this time that the incident with the landing ship Lesvos unfolded. The Lesvos, after leaving ELDYK [the Hellenic Force in Cyprus], engaged the Turkish forces. The Turkish forces in Cyprus reported that the Greek fleet had arrived, but the Lesvos sailed towards Israel while the Turkish ships headed towards Paphos. Turkish planes, mistakenly believing it was the Greek fleet, bombed and sank their own ships.”

In November 1974, Kremastoulis was transferred out of Cyprus, but he continued to serve in the Navy for another year. At the end of our discussion, we asked him about how he feels 49 years after the tragedy. As he reflects, “Many words are unnecessary.” The experience of betrayal and disappointment compelled him to emigrate to Mexico, he says. Today, he voices hope that today’s leaders will not repeat the mistakes of their predecessors, leaving Cyprus unprotected.