Jewish Salonika and the preservation of memory

Saadi Lévy Street; Modiano Market; Carasso Arcade; Saoul Arcade; Mizrahi Street; Villa Bianca; and Villa Allatini: these are just a few landmarks of the once vibrant Jewish Community of Thessaloniki… Should the task of safeguarding the memory of a decimated community fall primarily to its remaining members or to society as a whole? How many visible traces still attest to the culture of the Jews who inhabited Thessaloniki for centuries? Are these fragmentary snapshots enough? Can they recreate a unified image?

The struggle to do so is difficult largely because a distorted understanding of the truth resulted in people for decades interpreting the events that affected Thessaloniki during WWII according to their own political and national logic, making it impossible for them to grasp what had really happened. For years, memory was in danger of being erased in Thessaloniki.

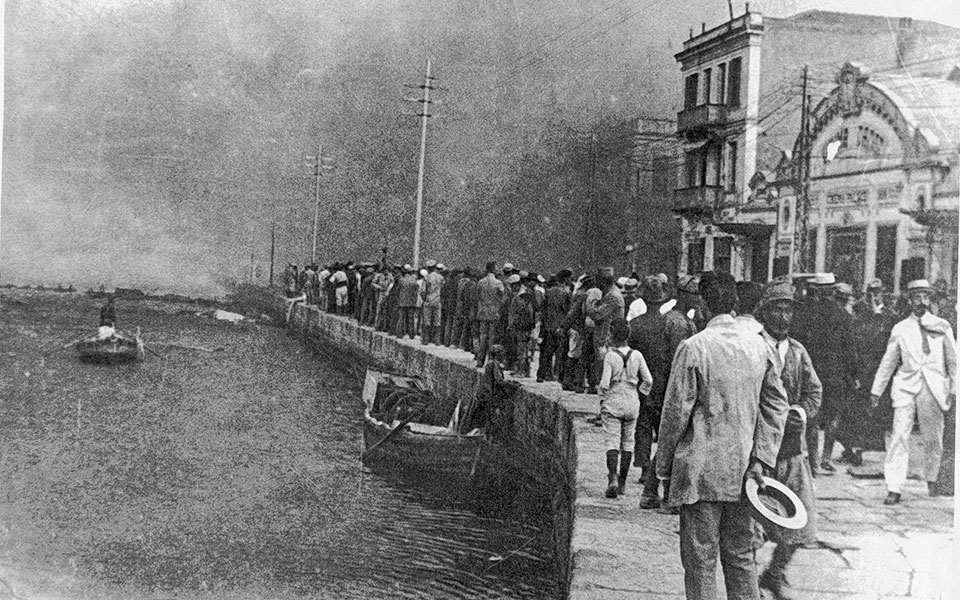

“The abundance of real suffering,” Adorno writes, “tolerates no forgetting.” Thessaloniki must remind those living in and visiting the city of the presence of hundreds of historic sites, monuments and remarkable figures connected with the glorious history of the Jewish community: the dozens of synagogues that were destroyed, the enormous Jewish cemetery (with over 300,000 graves), the old train station where the penultimate page in the drama of the community’s destruction was written, and the industries that changed the socioeconomic history of the city at the end of the 19th century (including the Olympus brewery owned by the Mizrahi and Fernandez-Diaz families, which later became the Fix factory). There were dozens of schools, cultural socities and philanthropic organizations, including the Joseph Isaac Nissim School and the Allatini Orphanage, and Ladino-language newspapers as well, and other many other enterprises testifying to the dynamic presence of Jews in the city.

The last witnesses

Nearly 80 years after the premeditated slaughter of most of the Jews of Thessaloniki, we are now witnessing the passing of that generation of men and women who weep, remembering the return of their few Jewish friends to the city, and the demise of those very few survivors who, scarred by their harrowing experiences, returned and tried to build a new life that still included their own customs and habits. Those very few, including my grandfather – who completed his military service in the Greek army at the end of the 1930s, fought on the Greek-Italian front alongside 11,000 other Jewish Greek comrades-in-arms, survived the Nazi death camps, and returned once more to Thessaloniki – often faced a climate of contempt, even from many institutional players in the city.

Many have wondered why those who returned to Thessaloniki never spoke of what they had experienced until decades later. They wanted to banish the image of death from their minds; they didn’t speak because their fortunes had been plundered; they didn’t speak because certain official entities allowed a synagogue to operate as a taverna for years; they didn’t speak because the community’s ancient cemetery had been entirely destroyed… Fortunately, many true fellow citizens supported them and softened the sting of this unfortunate reality.

Today, the problem isn’t merely that we will soon no longer be able to learn firsthand about the past. It’s also that, at the same time, as the witnesses to the greatest crime ever committed are disappearing, the voices of others are growing louder, others who keep denying this history. They deny, in fact, a crime whose perpetrators have repeatedly admitted their guilt. They deny the numbers tattooed on the arms of our grandmothers, deny that our grandfathers lost their entire families in extermination camps, deny the deaths, deny the humiliation. Fortunately, there is opposition to all this: the records of the collective memory of Thessaloniki, Greeks and foreigners, who insist on taking care of “lost” places and rebuilding the past in this “city of ghosts.”

The picture had already started to change during the 1980s. The decade saw an explosion of publications – the testimonials of survivors. The extermination at the concentration camps had already been fully substantiated by written sources, but only these first-person testimonials could give a sense of the complexity of the traumatic experience. The role and the inherent dignity of firsthand testimony were re-established. Seeing today’s doubts and denials of the genocide of the Jews, I wonder if all the efforts of the 1980s and 1990s were so much wasted breath: so many books, so many conferences and so many films that reenacted the drama and broke box-office records. That was the peak of global interest, as if the societies of Europe were struggling to heal that open “civilizational wound.”

It’s not easy, of course, to trace the historical route of so many “missing.” The urban fabric in Thessaloniki has suffered so much destruction and deterioration that it is difficult to recreate historical memory and bring the past alive again. Today, however, we can discuss these issues openly, and I want to believe that the shadows of denial hanging over not just Thessaloniki but the entire country are weak and belong to a small minority.

And yet they frequently make their presence felt. A recent example is the vandalism of the monument of the old Jewish cemetery at Aristotle University. One might say that news of “another incident of vandalism of the monument” is somehow routine, but this was not. Sometimes a moment comes when the perpetrators go beyond simple desecration and vandalism and dare to dream of the complete obliteration of the particular monument and of others (evident from the extent of the destruction they caused). The perpetrators dream, it seems, of the disappearance of the Jewish presence from Thessaloniki, even if that presence is just in the form of a monument! Perhaps they dream of repeating the act of their ideological ancestors, the destruction of the Jewish cemetery, an outrage and a sacrilege that went unpunished. The news about vandalism of this sort certainly does not constitute something routine.

An ideal institution

On the other hand, it may seem that there is something routine in the way various actors in the city now routinely condemn that vandalism. As for those that may want to destroy the memory of the graves that confirm the continued existence of the Jewish community of Thessaloniki, memory will remind them that the dead are more powerful than they are; human society is stronger than their barbarity. And it’s also worth noting that as recently as a few years ago, we didn’t even have the universal condemnation of these acts.

Fortunately, the rich history of the Jews of the city didn’t end with the genocide, despite the irreparable harm that the community suffered. The explosion of new writings in recent years about the history and the genocide of Greek Jews may have created the impression that these issues have been adequately covered by academic research, but we have not yet thoroughly examined the difficulties, often insurmountable, that the very few survivors of the Nazi atrocities faced on their return. Only in the past few years has attention been paid to the obstacles in the reintegration of Thessalonian Jews and the more urgent problems they faced, including, for instance, the premeditated destruction of the enormous Jewish cemetery.

In the past few years, all these issues have come again to the fore, partly because of the planned construction of the Holocaust Museum of Greece in Thessaloniki. Most people agree that the museum will need to confront and assess every aspect of antisemitism and not confine itself to an appeal to the emotions or to the recollection of nostalgic moments. The city, and indeed the country as a whole, needs a center that will consider the role played by refugees in the city over time, examine the relationships between Jews and the other inhabitants of Thessaloniki and the Balkans, and look at the contributions of important figures who left their mark on daily life in the city. We need an institution that will invite visitors to examine historical evidence, study the history of the other Jewish communities, and reconsider the activities of institutions and other bodies, including the Federacion Socialista Laboradera (Socialist Workers’ Federation).

The museum must also serve as a research center, shedding light on the brilliant past of the Jews in Thessaloniki and making it possible for us to understand the void caused by their violent extermination. It must focus on the lives of ordinary people and reflect the idea that the Jews of Thessaloniki constantly feel different – at school, in the army and in their dealings with many public services. The city needs a space of memory that will promote identification, present empathy and heighten the sense of historical drama. After all, Thessaloniki is a city that has repeatedly had to come to terms with recounting the past. The prefix re- is often a topic of conversation in the city; there are discussions on reconstructing, rebuilding and so many “re-s”.

The city and the country need a museum that will address itself not just to Jewish visitors, a museum primarily for young visitors and not just for tourists, an innovative museum that won’t simply provide information but will instead reveal the rich history and cultural singularity of the Jewish community of the city. It would be fascinating, if possible, to measure the level of knowledge of visitors before coming to the museum and then gauge what they took away from it, looking at the individual experience, whether social, religious or other.

This article first appeared in Greece Is (www.greece-is.com), a Kathimerini publishing initiative.