Our stories and our records belong to us

One of thousands of adoptees taken away from Greece in the 1950s and 60s, stripped of their citizenship and identities, shares her story story

It was under a bright, warm sun in June last year when I arrived at the Patriotic Institution for Social Welfare and Awareness (PIKPA), a building which holds secrets and history and heartache in its very bones. Comfortably set on a hillside of Penteli outside of Athens, I was there to find out more about myself. This was the place I likely came after I left an orphanage on my way to adoption by a Greek-American couple, strangers to my tiny self. I had issues with my lungs, which I still have 67 years later, and this is the place where people came for further treatment, for rehabilitation, a place to heal and rest.

It was under a bright, warm sun in June last year when I arrived at the Patriotic Institution for Social Welfare and Awareness (PIKPA), a building which holds secrets and history and heartache in its very bones. Comfortably set on a hillside of Penteli outside of Athens, I was there to find out more about myself. This was the place I likely came after I left an orphanage on my way to adoption by a Greek-American couple, strangers to my tiny self. I had issues with my lungs, which I still have 67 years later, and this is the place where people came for further treatment, for rehabilitation, a place to heal and rest.

This visit to PIKPA Penteli was part of my long journey to secure the remainder of my adoption records in order to learn about who I am and from whom I come. I came with journalist and award-winning podcaster Katerina Bakogianni, who is producing a series, “Born Greek,” about the so-called lost children of Greece. She was there as a friend and interpreter.

My mother gave birth to me at the Athens Maternity Hospital, which has long since been torn down. We spent nine precious days together. Somewhere. She took me to the Athens Municipal Orphanage (Vrefokomeio) and I became baby number 44488. From there, I went to PIKPA Penteli before going to a final foster home and then to America and new parents.

I am one of approximately 4,000 children and babies who were part of an historic, systematic export of children offered up for adoption. We Greek children were a first wave of mass adoptions, which included many nefarious acts of commodifying children. It happened with us, with the Irish, the Koreans, the Chinese, the Romanians, the Spanish. It still happens in parts of the world, including the United States. But we were the first. The Greeks.

I was greeted by a rotund woman. I can’t remember her name and it doesn’t matter. She was polite, but perfunctory, as she led me to her office. We sat opposite each other, my file there on the desk, with her folded hands resting on top of it. She was guarding it as if I would somehow snatch it from under her and run into the hills with it. My records were in an old tattered envelope, discolored and sad. Had it been waiting for my arrival all these years?

“There is nothing in here of interest,” she said without emotion. “Respectfully,” I replied, “You cannot possibly judge what is important to me and what is not. Everything in that envelope is important to me at this point.”

“You cannot have access to it,” she told me. “We have to protect the data within.”

“But it is MY data,” I politely insisted. “You are keeping me from myself in that file.”

She opened it in front of me and casually leafed through the papers, as if she was going through a catalogue to buy clothing. “Really, nothing here,” she said, as I stretched my neck to see anything. Something. “We have to protect your mother and father,” she said. “Their data.”

“My mother is dead,” I said. My father? “Is his name in that file,” I asked. “Yes,” she replied. “His name is here throughout.”

This was big news to me. I had recently had a meeting at the office of the Athens Municipal Orphanage. The orphanage has shut down, but there is an office that administers the files, remnants of small, powerless lives that were forever changed. They called me in to give me something I had been waiting for all my life. They had a document with the name of my father, which does not appear on my birth certificate or in any other papers I have in my possession. Someone who had been nonexistent was revealed. But in the PIKPA file his name is everywhere, according to the social worker. What does that mean?

This meant that perhaps my mother was not raped, which certainly could have been the case as it was for many other birthmothers who relinquished their children. My mind raced. Perhaps she knew him. Maybe knew him well. Maybe they were in love, I thought, which made me somehow so happy thinking that my parents loved each other and produced another human being together, a piece of the two of them. Me.

“Are you a mother,” I asked the social worker. “No,” she said, as she pulled off her reading glasses to look up at me, as if to say, “What is your point?” I was trying to make a connection with her, to soften her up so that we could perhaps understand each other on another level. I pulled out my phone to show her a picture of my mother. It was given to me by her brother. Granted, it is not a great photo and was obviously taken for an official document, a license, an identification card, perhaps.

I turned the phone toward her so she could see it as she repositioned her reading glasses on her nose, head cocked up, eyes looking down through the glasses. “She is not very attractive, is she?” she said without one spot of emotion. I was stunned. Who would say such a thing? I was there with my heart in my hands. She was my mother. I said not a word and clicked the phone off, my hand shaking. I was embarrassed that I had revealed any vulnerability, now feeling more vulnerable than ever.

We Greek children were a first wave of mass adoptions, which included many nefarious acts of commodifying children

There is nothing more to say about this visit except that I left with nothing and there is an injustice in that. I deserve to know every single record that exists about the circumstances of my birth, my parents, my journey, my kin, my medical history. This is my right. To have my “data” returned.

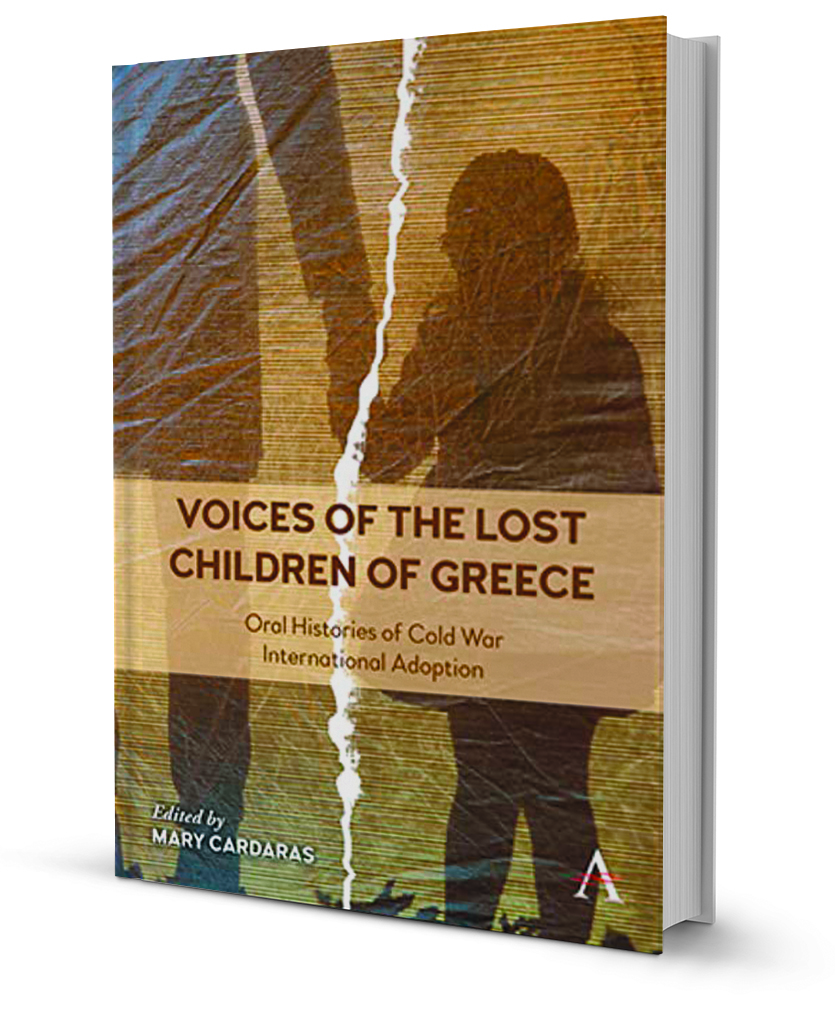

I write this as a book I proposed and edited has just been published. It is called “Voices of the Lost Children of Greece” (Anthem, 2023), a first-of-its-kind collection of essays from 14 Greek-born adoptees, mine included. It will be translated into Greek this year by Potamos Publishers in Athens. The essayists paint very intimate self-portraits, telling very difficult stories about their lives as adopted people. Robyn and Maria tell stories of repeated abuse. Robert tells about being ripped from a twin. Alexa has a memory at age 4 about trauma in the orphanage. David’s mother has waited all her life for his return. Sonia learns that her mother had a serious illness, which could have affected her as well. Ellen is born Greek, and adopted by Jews. She found a sibling only to lose her again.

The collection is both a plea and prayer from me to the Greek government and anyone in power, someone who will listen and can actually do something. We need someone to take us seriously, to understand why it is important to know what happened to us, to know the fractured details of our lives.

For the past four years I have spoken publicly, appeared in numerous articles, written articles myself, been interviewed on television, on radio and been a guest on an assorted number of webinars. I’ve spoken with ministers and lawyers and even a confidante of the prime minister himself. So has Professor Gonda Van Steen, with me, who wrote the seminal book “Adoption, Memory, and Cold War Greece: Kid Pro Quo?” (University of Michigan Press, 2019). That book started a very public adoptee movement for justice and brought Greeks more in touch with their history and even exposed this history to Greeks who knew little to nothing about it.

This is the age of transparency. This is the age of acknowledging historical injustices. It’s what makes us human. It’s what makes governments progressive and great. To say we are sorry for what happened. To say we are going to fix it. And as someone who was once very close to the prime minister said to me: “I get it. Nostos. Nostos for these people, these Greek-born adoptees. This is not complicated, Mary.” He was right. It’s not.

God knows, we have had numerous people who have said they will focus and champion this issue for Greek-born adoptees. Many we have not heard from again. Some have taken meetings and we’ve hashed and rehashed the issue only to be told, “We’ll research this, we’ll think about it and have more meetings about it,” with no meaningful movement. And others, only a few, have even been rather hostile and insensitive, turning a deaf ear. “Why must these people live in the past?” they ask. “These children’s lives were saved, they would have died otherwise,” they say. “Why can’t they just be happy with their lives now and forget it?” they declare. To those struggling to understand, I ask for them to please put yourselves in our shoes.

Many of our lives were not happy. Some of us were abused emotionally and sexually. Some of us were stolen. Some of us know not a single biological relative. We all helped to make new families with strangers while our families of origin were destroyed in order to do it. Birthmothers were left scarred for life. With support, they could have raised their own children. Birthfathers were sadly rendered completely unimportant. Millions and millions of people around the world pay money to Ancestry and 23 and Me and other similar commercial DNA testing services to find out who they are, where they come from. Why? Because it matters. We need and want to know the same for us and we are so close to the sources of that information.

If only a champion in the government were specifically appointed by the prime minister to help us and to be held accountable for results so that this sad history could be put behind us. For good. Trust me, it would only enhance his chances to be re-elected prime minister. Can you imagine a grand, magnanimous gesture, orchestrated by the Mitsotakis administration itself, an event, a gala in which as many of us as possible return to Greece for a ceremony to restore our citizenship and be welcomed back home? At the very least it would be a public relations coup for Kyriakos Mitsotakis, but it would really be a symbol that the government understands the right thing to do at this moment in history.

Also, rest assured that we would be coming home sooner than the marbles, and of our own volition! Other governments are welcoming back their adopted children and taking responsibility for the long-lasting scars they helped to impose. Greece needs to join the community of nations in doing the same for its 4,000 adopted children. Further, how can it be that the government of Greece hands citizenship to people who have no organic connection to Greece, only that they wrote about it or studied it or invested money in the country? If those people, why not also us? We were born in the country and had Greek parents, but were stripped of our passports and our identities, without our consent. Wouldn’t it make sense to right that wrong?

We agree. There needs to be a systematic approach to a careful process, but in the end an adoptee, with the help of a representative from the government, academics and social workers, proves their identity. In turn, the adoptee is given full access to their adoption records and has the opportunity, if they wish, to have their Greek citizenship restored. Why? Because we are children of Greece and we love our country. And loving Greece means visiting it and bringing others, who will also fall in love with it. Also, there is a measure of respect that Greece will earn by looking this particular history in the eye and coming to terms with it in the open.

Last December I went with someone very dear to me to visit the grave of my birthmother. I met her young caretaker, who loved her like a mother. I went to her village, saw where she lived and loved a partner for many years. I met her friends. They told me about her and marveled at how much I looked like her, walked like her, the resonance of my deep, low voice, like hers. Her caretaker gave me my mother’s coat. My instinct was to bring the garment to my face. The coat still has the scent of my mother’s perfume on it.

During that visit, a friend of my mother, now in his 70s, broke down in tears. He said, “Mary, I feel like you were sent here from God.” When he was 10 his mother gave birth to a second child on May 10, 1958. It was a normal pregnancy. No complications. The birth was also normal at a regional hospital. The mother heard her baby let out a healthy, strong cry. Later, though, she was told her baby died. There was no death certificate. Her baby’s body was not brought to her at all. In their grief, they could do nothing. This tragic scene, sadly, was not uncommon during a very turbulent time in the country. It was played out in villages over and over again. Parents were told their children had died with nothing to prove it. What happened in many cases is that those children were stolen and given to other parents, sold by intermediaries, and were “adopted” under the table.

In this case, the mother told her son on her deathbed, “Promise me you will find your brother.” “He did not die,” she said, absolutely convinced of it. “He was taken from us and he is alive.” This man told me he felt enormous guilt that years had passed and he had not looked for his sibling, but meeting me was a sign that it was time. I recommended that he and sister provide DNA samples immediately. I told him there is a reasonable chance that his brother is looking for his family and has no records connecting him to anyone. He may have even registered his own DNA results, I said, and he might be waiting for them to appear.

There is hope. I know it because I have seen other adoptees find their birth families when there was only scant evidence, an absence of detail and where any hope at all seemed nowhere to be found.

This story is one of hundreds that still linger decades after the fact. It is time to help those who want reunification with kin. To help reunite aging adoptees with their adoption records. To bring the hundreds of stories of loss full circle so that there can finally be peace in knowing the truth and to bring closure, not only for the lost children of Greece and their birth families, but also for a government that needs to put this ugly, heart-wrenching remnant of its past in the rearview mirror, and for good.

Mary Cardaras, an adoptee activist, holds a PhD in public and international affairs from Northeastern University and a master of science degree in journalism from Northwestern University. She is associate professor and chair of political science at California State University, East Bay, where she teaches journalism and political communication. She has been a producer, journalist, and documentary filmmaker for over 40 years. Currently, she produces documentary shorts about the effects of the environment on public health. She is the director of The Demos Center, which focuses on the intersectionality of democracy, public policy, a free press, and rhetoric and leadership, based in Athens at The American College of Greece.