Stumbling across Kastoria’s history

Story of Filippos Kosmas and the Eliyahus a reminder of the near-annihilation of the town’s Jews

I visited my dear uncle Filippos Kosmas’ farm on the outskirts of Kastoria in Western Macedonia recently. I had good reason for doing so. My family and I have been trustees of his real estate holdings in the town since he passed away in 1996 and there was a person interested in the estate, which consists of a farm and a 60-square meter house used mainly for storage.

As a result of break-ins and time, the house was so littered with ashes, cotton stuffing from dilapidated cushions, rocks and dirt, I could hardly see the floor. Making my way back outside, I stepped on a piece of flat metal, making a loud noise that startled the birds nesting in the fireplace. After all, there were no doors and windows to speak of. After walking a few meters toward the main gate, I suddenly decided to go back, drawn to that piece of metal: Perhaps it was an old sign from my uncle’s fur shop, I thought.

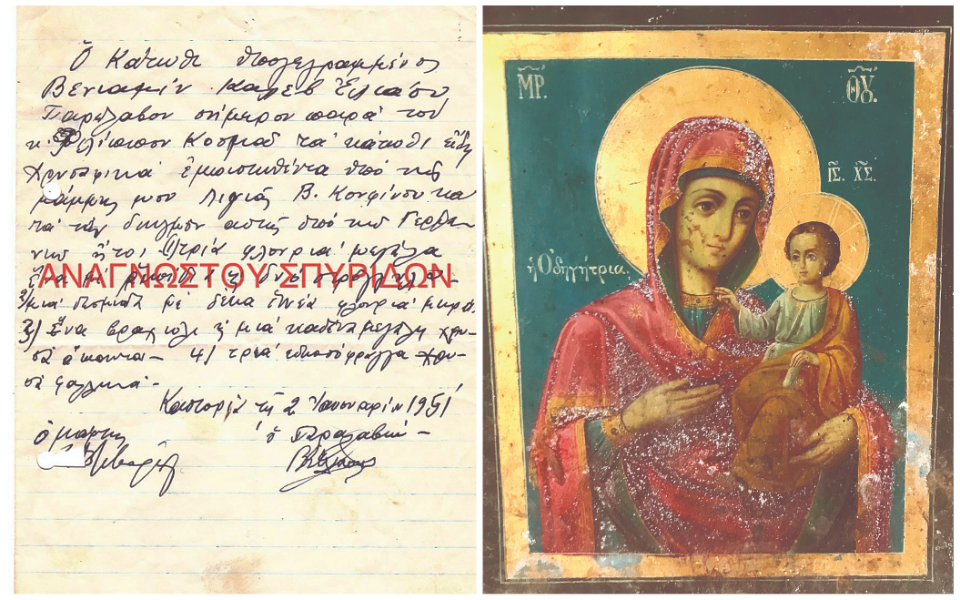

I carefully took hold of one corner and lifted it up, to see a likeness of the Virgin Mary on the other side of the metal sheet. It was a pretty and well-executed painting, but that’s not all. Hiding beneath the metal was a bunch of papers: bills, old invoices and a document written by hand. I grabbed it all up and took it away, so I could examine my finds at my own leisure back home.

That handwritten document turned out to be something of a treasure, a confirmation of Uncle Filippos’ moral virtue, but also his kind nature. “Barbatsoulis,” as he was nicknamed, was born in Kastoria in 1909, the son of Ioannis Kosmas and Maria Bouziota. He attended high school locally and left for France after graduating, becoming involved in the fur trade and eventually going on to become a successful and respected international merchant.

Also a philanthropist and benefactor, he bequeathed much of his fortune to the town of Kastoria. He was the founder and president of the local sailing club and headed the municipal council for several years.

To me, however, he was just Uncle Filippos, but he was also the person who encouraged me to continue his collection of old objects, giving me a lot of family heirlooms. Even when my parents became frustrated by my growing collection, he found a way to give me more. He always found a way, even if it was on the sly.

Moschopoleos Street

My uncle’s house was in Kastoria’s Omonia Square; a unique sample of eclecticism, with an oriel window looking out to the square and a big balcony over Moschopoleos Street on the other side. It shared a wall with the equally beautiful home (it’s still there today) of Benjamin Confino, whose daughter, Allegra, was married to Calev Eliyahu. My uncle’s home was, unfortunately, demolished sometime in the 1970s, though he rebuilt it.

Calev Eliyahu owned the city’s biggest mill, in the Bouzbounari area, and was also a very active president of the Jewish Community of Kastoria. The community numbered some 1,000 Jews at the time, quiet folk who lived with the Christians in harmony, mainly on Tsarsi (the chief commercial thoroughfare) and present-day Mitropoleos Street, in Toumba.

One cold March day, the Germans rounded them all up at the local school, until their final departure on March 24, 1944. Of them, just 35 survived. The rest would never see beautiful Kastoria again.

Shame and tears

The snow was black as it fell that morning. Allegra went onto the balcony of the house on Moschopoleos Street in fright and called out to Uncle Filippos, who was on the nearby balcony of his home. She held a small purse in her hand with a few gold coins and some items of jewelry. “Take them… They’re rounding us up to take us away. You can return them if we make it back; if not, keep them to remember us by,” she said.

After much pain, hardship and heartache, only two of the Eliyahu family of seven made it back. The two siblings were found after much turmoil thanks to the Red Cross and returned to Kastoria briefly in 1951. Beni and Lena were among the town’s 35 survivors. Their mother Allegra, their brother Mosiko, aged 8, and their younger sister Sheli, 6, were exterminated in the gas chambers soon after arriving at Auschwitz. Their father Calev was deemed “fit for work” when he arrived at the forced labor camp and was not taken to the gas chamber. He eventually died on one of the death marches, together with his son Vital.

The story of the two rescued siblings is beautifully told in the documentary “Trezoros: The Lost Jews of Kastoria,” by Lena’s son, director and producer Lawrence Russo, and Larry Confino. It has been shown in theaters all over the world, as well as on many television networks (www.trezoros.com).

When they got back to Kastoria, Beni and Lena went to visit Uncle Filippos, who told them the story of the family heirlooms he had kept safe for them. The return of the gold coins and jewelry was witnessed by Michel Mevorah, another of the 35 survivors, with his seal on a document certifying not just that the items were returned but also attesting to Filippos’ honesty.

This document was the “treasure” beneath the metal sheet. The icon of the Virgin Mary acted as a shield, protecting this valuable document all these years. And even though I do not believe in that sort of thing, I cannot help wonder about the series of coincidences that led to its discovery. It came as confirmation that I am on the right path. And that path, which I have been steadfastly committed to since I was a boy, is the preservation of historical memory. It’s as if once more, Uncle Filippos found a way to add to my collection.

Today there is little in Kastoria to remind us of the existence of that tortured community, save a street called Evraidos and a monument at the school where they were rounded up to be sent to the death camps. That and the stories told by the old-timers. This is one such story, told to me by my aunt Maria Douma, Filippos’ daughter, many years ago. Thankfully there were people to preserve these memories, people whose compassion went some way to counterbalance the shame of the actions of some of the other townfolk, who rushed to plunder the homes and fortunes of the Jews just hours after they were violently torn from their roots, actions somewhat offset by the tears shed by many Kastorians when they learned of their friends’ violent persecution.

The Jews of Kastoria who did return donated land and buildings to the town as it grew and developed at a rapid pace. More importantly, however, they passed on their love for their hometown and for its residents to their children and grandchildren.

In memoriam

I dedicate this piece to our lost Jewish brothers and sisters… to the memory of Lena Rousso, Beni Elias and my uncle Filippos Kosmas.

I would also like to thank Larry Rousso for allowing me to use these exceptionally rare family photographs and for the information.

Even though we met several years ago in Kastoria, little could we have imagined that we’d ever be connected in such a way. He remembers his mother speaking of the kind neighbors who salvaged the family heirlooms.

And to my aunt, Maria Douma, for her support in my quest to know more of the family and local history, and to researcher Babis Athanasiou, who helped me identify the owners of the Confinos house.

Spyridon Anagnostou is a researcher of Kastorian history.