Santorini’s underwater Kolumbo volcano under observation

“If Kolumbo lights up, we’re done for, child,” distinguished marine geologist Evi Nomikou remembers her grandfather – a farmer from Vothonas – warning, speaking of the danger lurking in the underwater volcano cluster off the coast of Santorini, even back when she was in elementary school in the 1980s.

“To this day, some people continue to confuse it with the Nea Kameni volcano in the caldera, which is terrestrial. The last time Kolumbo erupted – at least in a way that was visible to the naked eye – was in 1650, spewing toxic gases that killed dozens of residents and hundreds of animals, and causing a tsunami. It was an incident that became deeply ingrained in local memory and was passed down from generation to generation, until it reached my grandfather and then me,” she tells Kathimerini.

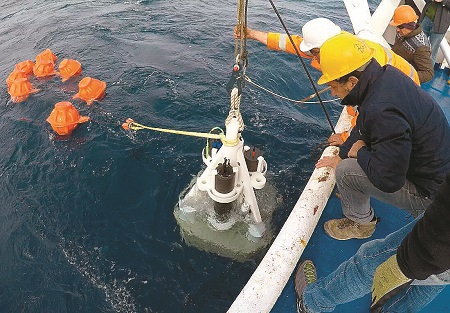

Nomikou, an assistant professor at the University of Athens’ Department of Geology and Geoenvironment, is the driving force behind a number of scientific projects related to volcanic activity on and around her native Santorini. The most recent of these is called Santory (Santorini’s Seafloor Volcanic Observatory) and aims, for the first time, to put the Kolumbo volcano under close and regular scientific observation. It utilizes special underwater machines and cameras to collect data at a depth of 500 meters on hydrothermal fluids and volcanic gases, as well as changes in the seabed and temperature fluctuations. These all provide an indication of impending volcanic activity, known as “precursor phenomena” by the experts.

Nomikou, an assistant professor at the University of Athens’ Department of Geology and Geoenvironment, is the driving force behind a number of scientific projects related to volcanic activity on and around her native Santorini. The most recent of these is called Santory (Santorini’s Seafloor Volcanic Observatory) and aims, for the first time, to put the Kolumbo volcano under close and regular scientific observation. It utilizes special underwater machines and cameras to collect data at a depth of 500 meters on hydrothermal fluids and volcanic gases, as well as changes in the seabed and temperature fluctuations. These all provide an indication of impending volcanic activity, known as “precursor phenomena” by the experts.

“It is a critical endeavor in terms of civil protection for an island with so much tourism. The common practice, until now, was to only monitor terrestrial volcanoes like the one on Nea Kameni. Kolumbo was only monitored sporadically, never on a systematic basis,” says Nomikou.

Santory’s scientific partners in the project are Nomikou’s department at Athens University, the Hellenic Center for Marine Research (HCMR), the National Technical University of Athens’ School of Rural and Surveying Engineering and the University of West Attica’s Department of Surveying and Geoinformatics Engineering.

It is also getting know-how from Italy’s INGV Palermo, the Geosciences Department of the Ecole Nationale Superieure in France and Germany’s GEOMAR. The project’s 600,000 euros of funding comes from the Hellenic Foundation for Research & Innovation (ELIDEK).

“That money will allow us to buy but also build, in Greece, innovative marine technology machines for monitoring the volcano. These will be brought up from the sea every so often and then placed back in the crater,” says Nomikou.

“That money will allow us to buy but also build, in Greece, innovative marine technology machines for monitoring the volcano. These will be brought up from the sea every so often and then placed back in the crater,” says Nomikou.

“The Municipality of Thera is an important contributor to our scientific work and our future goal is for data to be transmitted in real time from the Kolumbo crater to a special, pioneering volcano observatory on Santorini,” she adds.