Light shed on Greece and Poland’s entwined past

Polish journalist Dionisios Sturis wondered recently what it was that attracted him to cover the journey that refugees from Syria made through Greece. He concluded that it was the “refugee gene,” as he calls it, that he carries.

Sturis’s family fought with or supported the Communist Party-founded Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) in the 1946-49 Greek Civil War. They joined the thousands of Greeks who fled the country after the communists were defeated in 1949, mostly remaining in exile until socialist PASOK came to power in 1981 and allowed them to return to their homeland.

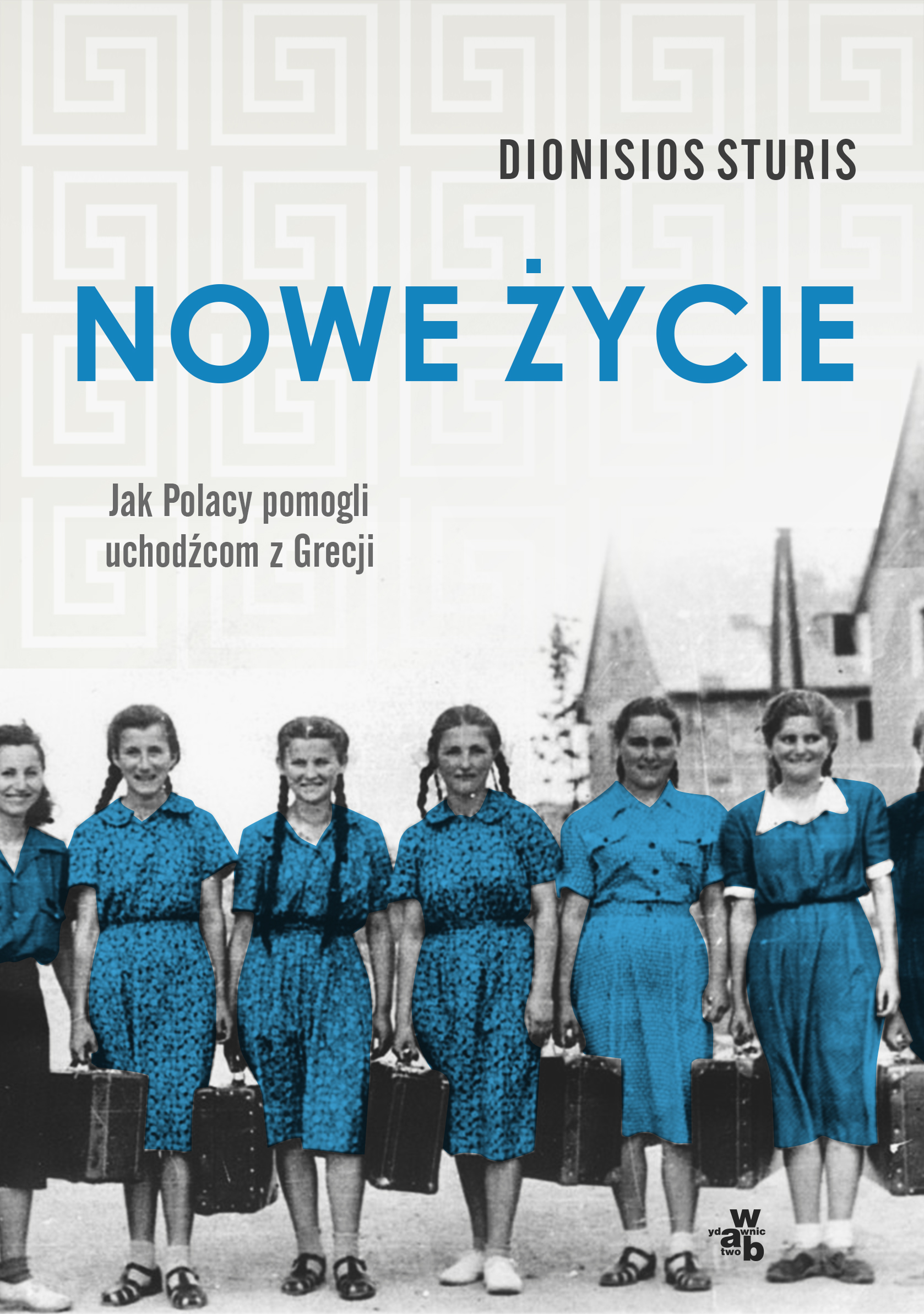

In the meantime, though, many of the exiles forged new lives abroad. Sturis’s relatives settled in Poland, along with some 14,000 others from Greece. He examines their stories in the book “Nowe Zycie” (New Life), which has recently been published in Poland.

The book was a personal journey for Sturis but also an attempt to shed light on an aspect of Greek and Polish history that has, in his view, been overlooked. He spoke to Kathimerini English Edition about the stories of those involved and why their experience is still relevant in Poland today.

Is your book an attempt to tell the story of the Greeks who fled to Poland as a whole or are you trying to highlight individual experiences and what they tell us about this period of history in the two countries?

The fascinating story of refugees from Greece in Poland is almost entirely forgotten. It was never properly told. Even people who used to have Greek or Macedonian [Editor’s note: The author is referring to people from Greece whom officials termed “locals” (ntopioi). Greece does not recognize a distinct “Macedonian,” ethnic identity.] neighbors, colleagues, friends or lovers know very little of them and of the reasons behind their arrival in Poland. With my book, I try to fill that void. I present individual stories of people I interviewed both in Poland and in Greece and what comes out of it is a sort of a group portrait. But it is also a report on true and beautiful solidarity toward people in need as it was shown by the Polish communist state and by the Polish people. A solidarity that is nowadays lacking.

What were the circumstances in which the Greeks arrived in Poland and how were they treated by those who received them?

Poland was a destroyed, traumatized and very poor country. People were still healing their war wounds. Hundreds of thousands were being sent to a territory in the west, which before 1939 belonged to Germany. It was now called “Reclaimed Land,” a part of Poland that needed new residents. They were people from the other end of the country, it was the Jews who survived the Holocaust and from 1948 onward it was refugees from Greece. At first it was almost 4,000 children of the “paidososimo” (the removal of children from Communist-supporting families to countries considered safer), and among them many orphans. They arrived either by train or by ship – hungry, ill, petrified. They were put into health resorts where wealthy Germans used to come for treatment. They were cured of all the diseases, fed, clothed and taken care of in an extraordinary way – with love and compassion. Many of them, like my aunt Kiriaki, are now in their 80s and they still remember the very first day on Polish soil – how they hid bread, apples and candies, out of fear there wouldn’t be anymore. Hearing a plane, they would crawl under their beds to seek shelter, shout and cry.

Then there were the wounded members of the DSE (Democratic Army of Greece). There was a secret hospital organized especially for them in a small town of Dziwnow by the Baltic Sea. They suffered from all kinds of diseases and were physically exhausted, with bullets still in their heads or limbs. Many who arrived without legs or arms needed an instant reamputation. Almost 2,000 people got comprehensive treatment there, which included surgeries, physiotherapy, dentures and glass eyes. I know of people who still use the wooden prostheses they were given almost 70 years ago.

The last group were defeated “andartes” (rebels) and their families. Altogether it was almost 14,000 people.

At first, they were all transferred to Zgorzelec, a town by the German border. It soon became known as “Little Athens” or “Little Greece” as the refugees were a majority. They seemed exotic to their neighbors – they looked a bit different, spoke a different language, cooked different food, yet they encountered openness. People weren’t scared of them. They were curious and ready to help. That’s how friendships first emerged and the first Polish-Greek marriages. After a year the refugees spread all over Poland, to dozens of cities and towns. One of them was Chojnow – my hometown. They even made it to the other side of the country and settled in a few small villages by the Ukrainian border, such as Kroscienko. It became a Greek village. The newcomers opened a cooperative called Nea Zoi which was highly successful and employed close to 1,000 people. It operates to this day. I went there and spoke to the few remaining Greeks – the village head is a lady called Danusia, whose father was a refugee from Greece. There is a Greek cemetery there and a monument to Nikos Beloyannis. Greek or Macedonian names don’t surprise anyone in Kroscienko.

What kind of involvement did Poland have in Greece’s civil war?

This is another forgotten story, and one that Poles have no idea about. But I also think that the Greeks do not know much about the extent of assistance that was granted to the DSE by Poland and other countries of our region. Until recently even historians had limited access to that knowledge. The support for Greek andartes was huge but still far smaller than the help given to the other side by the Americans. It started in 1947. Nikos Zachariadis, head of the KKE (Communist Party), asked Stalin for support, not knowing he had had a secret deal with Winston Churchill from 1944 and therefore could not get fully involved. But he could delegate that duty to leaders in countries under Soviet influence. One of them was Polish President Boleslaw Bierut. He could have refused, given Poland’s dire situation, but he chose not to. He believed in the idea of proletarian internationalism. So, in the early autumn of 1947 a huge shipment was sent to Greece that included among other things 10,000 pairs of shoes, 10,000 shirts, 4 million bullets, over 5,000 rifles and guns, 2,500 land mines and 25 tons of medical supplies.

For the next two years Poland coordinated the whole operation. Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania would send over their share, we would add ours and off went the ships to the Albanian port of Durres, carrying tens of thousands of tons of food (including flour, chocolate, sugar, coffee, pasta, tinned meat) and massive weaponry loads, some of which had previously been confiscated from the Germans at the end of World War II. The same ships on their journeys back would bring over the paidososimo children and the wounded fighters headed for the secret hospital.

Once the Greeks had settled in Poland, what became of them? Where did they live and what did they do?

At first, they were being told to be ready for another fight, to sleep with “opla para poda” (arms at the ready), because apparently the war would break out again soon and they would have to go back to Greece. When that turned out to be fantasy, the refugees started to settle in. They began a new life in a country they previously had no idea about. It was not easy but I heard many stories of those early years when the Poles proved to be welcoming and helpful. They made the whole situation easier for their new Greek and Macedonian neighbors, even if it was just little things like shopping, visits to a doctor, writing a letter, childminding, or finding a proper coat for hard Polish winters.

All the refugees got jobs – mainly in factories or in agriculture. The invalids worked in special cooperatives. They were given opportunities to enroll in a language course or get additional vocational training.

It wasn’t long before they made friends with their Polish neighbors and colleagues from work. But at the same time, they cared very much about their “Greekness.” In every town and city where there were Greeks, there were “Greek clubs.” The refugees gathered there every evening to play “tavli” (backgammon), to talk politics, to gossip, to teach their children Greek and practice Greek dances. They partied together (often with their invited Polish friends) and whenever there was a celebration they repeated the same toast: “Kai tou xronou stin Ellada” (And next year in Greece). Vodka was a popular substitute for ouzo, pickled herrings replaced olives.

Pictures from those parties were often printed in a refugee newspaper called “Dimokratis” – now available in the Polish National Library. At first it was a daily paper, later a weekly magazine, then a monthly bulletin. Written both in Greek and Macedonian, it brought important news from Greece and the world, but most importantly it chronicled the life of refugees in Poland – who married who, who died, who’d had a child, who’d moved to Kroscienko, where the Greek mandolin band was going to be in concert next, which Greek students won medals in school sport competitions, and where one could get real feta cheese.

What was the fate of the orphans who arrived from Greece?

Not all of them were orphans. Many had parents or at least one of them, so they waited for them to come to Poland to be reunited. But that took years, and before it was possible the children were placed in special care centers and were looked after by Polish, Greek and Macedonian carers. These children are now in their 70s and 80s and they all remember those times as the best in their lives. They were never hungry, they were healthy, full of energy, they joined the Polish scouting movement, they excelled in sports and art – especially in music, as there were many dance and singing groups. At first, they attended schools in the centers, but after a few years they were put in Polish schools, where they were welcomed. I read stories of young Greek students who’d win speech contests, reciting Polish poetry, or who became national champions in athletics. They were treated the same way as the Polish children, they had truly equal opportunities. Many of those children entered universities later in life and became doctors, engineers, artists or musicians.

From the people you have spoken to, do you get a sense that the Greeks who went to Poland saw themselves as having an opportunity to start a new life after traumatic events in Greece or were they always burdened by a sense of loss?

There is no good answer to that question. These people knew very well what sort of life they would have, had they stayed in Greece. They followed the disgraceful Beloyannis trial (he also spent some time in Poland after the war before returning to Athens), they knew of the persecutions of the communists and the left in general. They had to live knowing that because of their past in the DSE their innocent fathers and uncles were given sentences of 10 to 20 years in prison or on Makronisos [an island off the coast of Attica hosting a prison for exiles]. So, there was grief and anger. But there was a longing too. Greece was their country, their homeland, they shed blood for it. They shouldn’t be here, in a faraway country. But on the other hand, that country saved them. It cured their wounds, it sheltered their children, it gave them opportunities they would never have in Greece. Ninety-five percent of the refugees in Poland could barely read, never visited a cinema or theater, never traveled. Yet in a village of Kroscienko they had their own cinema (organized in an old church), they had kindergartens and schools, their children graduated from universities. It was a huge difference. And that is why many people I interviewed emphasize how grateful they are – both toward the Polish state and the Polish people. They talk of kindness, friendship, understanding and compassion.

On a personal level, did the Greeks find a way to get on with the Poles? What kind of things brought them together?

It happened naturally. The Poles remembered too well what war was and in the refugees, they saw victims of yet another war who needed support. So they were open toward them. There were lone quarrels and fights or bullying but on a level not worth mentioning. The Greeks were seen as very hardworking, honest and clever. After they learned to speak Polish and laid their roots, they stopped being exotic, stopped being “the other.” Especially the second generation – people born in Poland. Kids at school would give them Polish names and treat them like everybody else.

The dream of return

You say that the toast at family gatherings and celebrations was always the same: “And next year in Greece.” When this moment arrived and the Greeks could return from Poland, what was the experience like for them?

There were mixed feelings and emotions. Happiness and joy, reluctance and fears. Their dream was finally coming true, but after almost three decades in Poland was it still a dream? What happens next? Men would pack their bags and return immediately, women on the other hand hesitated. My aunt didn’t want to leave her home, her friends or take her kids from the local school. She felt as if she was abandoning the life she managed to build. But she didn’t have much choice. So, they rented a train carriage, packed everything they had and left. To begin yet another new life. People were anxious also because they did not know what they are going to see upon return. It would surely be a different place than what they remembered, a different country. Their Greece was long gone. What about their relatives, would they remember and welcome them? Would they give them their part of the inheritance, a piece of land their parents left to be shared among the siblings? Many took the risk. Their experiences varied. Some were welcomed with love, some with anger.

They also had to face another challenge – anti-communist propaganda. The Greeks imagined Poland of the late 70s as a wild country. My aunt was astonished when her new neighbors in Larissa asked her if it was true that Poles are so poor they eat with pigs.

There were cases of people not returning to Greece even when they could. How did they explain that decision to you?

The returns took years. Some people needed a whole decade to make that decision. Old people waited for the Polish and Greek governments to strike a deal on their pensions – that eventually happened in 1985. After that a few more families left Poland. Although some never did. For various reasons. Their wife or husband was Polish, their kids were more Polish than Greek. They had no one waiting for them in Greece. They couldn’t afford the journey. They loved Poland and couldn’t imagine living anywhere else. There is an old lady in Kroscienko who fought in the civil war. Her family never returned for these reasons. When we spoke, she added a few extra ones. Her late husband and many friends were buried in a small cemetery in Kroscienko – how could she leave their graves? One other thing – in a grocery shop in a nearby town she could finally buy “lokoumades” and olives. That’s all she needs. A separate group of people who chose not to go back were the Macedonians. They could apply for permission but they would have to first change their names to Greek. For many of them it was too high a price. They felt cheated and betrayed.

Refugee gene and obligation

Was the process of writing also a personal journey for you to find out more about what your family encountered?

Definitely. I finally understood what brought my family to Poland. It made me realize how tragically the wars affected their existence and mine. My uncles were members of the DSE, my grandmother secretly fed them at night. For that she was so severely beaten by the soldiers of the other side that she nearly miscarried when she was pregnant with my father. When he was little, the whole family escaped, hoping to save their lives. They found safety in Poland. And here we are, almost 70 years later. I am a Polish journalist often reporting on the refugee crisis with people fleeing Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan or Somalia. Until recently I didn’t realize why I choose to go to places like the Greek-Turkish border where in the past refugees would drown in the Evros River, or to Jordan or Kos or Lesvos; why I am so interested in their story, why their tragic situation bothers me so much. Working on that book made me understand it a bit more. In a sense, we share a common experience. I also have a refugee gene and therefore an obligation.

Did you get the answers you were looking for on the personal and journalistic levels?

The book is getting good reviews and I get feedback from many readers so it seems I probably managed one thing: to bring back the forgotten memory of the refugees from Greece. The void is no longer there, at least partially. I am also very happy I met all the people whose stories I put into my book – they are my people too. I am one of them.

Do you feel your book has a relevance beyond the small community of Greeks who lived in Poland?

I hope so as I believe it can be read from different perspectives. The Greeks will see it as a chronicle of their odyssey and as a tale of a split identity of every refugee: Who are we? Are we Greeks or are we “Polish Greeks”? Are we Greek enough?

The Polish readers, on the other hand, will perceive the story in the book as a proof of their humanity, kindness and hospitality, which are nowadays often replaced by xenophobia, racism and Islamophobia.

It can also be read as yet another story on wars and tragedies they result in. One of them being people having to flee their homes and countries. Centuries pass and that doesn’t change.

The migrant crisis

Poland has recently come in for some criticism about its approach to the refugee crisis, although other Eastern European and Balkan countries have followed a similar approach. Are there aspects of your book that can be useful for the current debate about refugees in Europe?

The Polish government is made up of populists and racists. They are cynically using the refugees as a political tool. They are trying to convince us that there is no difference between a refugee and a terrorist. They want us to be afraid of them because it is easier to run a frightened society. They can promise us that they will protect us from the Muslim rapists and murderers. It’s awful but it’s effective. Two years ago, more than half of the Poles were ready to welcome refugees in our country. Today, two-thirds are against it. Our politicians plan on building barracks for every refugee that crosses our border – barracks behind barbed wire. They are disgraceful. They won’t even accept unaccompanied minors and orphans who await mercy in camps in Greece and Italy.

Maybe if we remembered refugees from Greece we wouldn’t be fooled that easily? A refugee story can be a success story – if we are open and willing to help. If we could do it a few years after the war, when we were poor and no one expected it from us, why can’t we do it today – when we are wealthy and prosperous? Shame on us.