Building defenses for cyberwarfare

The head of Microsoft talks to Kathimerini about how the company thwarts such attacks against Ukraine and its investment plans in Greece

For Brad Smith, president and vice chair of Microsoft, the war in Ukraine is like the Spanish Civil War. It was then that aircraft were used for the first time in conjunction with the army and tanks to create a new technological approach to warfare. Now, in Ukraine, the combination of conventional and electronic warfare is being tested. The head of Microsoft explains in detail the tech giant’s role in the digital battles taking place as part of the war, on the side of Ukraine.

But he also talks about the company’s investment, cultural and educational plans in Greece, and explains his optimism about the country’s growth prospects. He makes no secret of his concern about the way social networking platforms are still operating. When he is asked about the consequences that Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter will have on the platform, he answers cryptically, “I didn’t get a vote.”

I remember, when we last met two years ago, you were very worried about the state of democracy and its future. Are you more worried now or are you less concerned?

I think in some ways there’s more cause for worry today. We continue to see these political cycles in many countries around the world that are characterized by more and more polarization and I think that’s a challenge. If there’s one thing that we, at Microsoft, have focused more in doing, it’s understanding how nation-state cybersecurity attacks have been now really coupled with the use of technology to exploit the spread of propaganda. The person who got me very focused on this coincidence – and perhaps ironically – was President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. And this was before the war. I was talking to him about what he was seeing the Russians do in Ukraine with respect to vaccine disinformation campaigns. And so we’ve really increased our capability, we’ve done an acquisition, we now have data. You can see a little bit of this in the report we published about defending Ukraine on June 22 of this year. But what we’re seeing is that it’s not just domestic polarization. It is deliberate nation-state efforts by countries like Russia or Iran to try to sow this discord and dissent, and lack of trust. That’s a pretty toxic and even potentially dangerous recipe. Ultimately, I believe we’ll manage through this, but we won’t really know until we get to the middle of this decade whether we’re succeeding in a way that should give us long-term confidence.

But again, do you think the answer to this is more regulation on social media? Is this going to self-regulate?

Since I was here last year, regulators have been moving towards more energetic regulation, and social media has definitely been one of the big factors leading that to happen. We’re seeing that in the Digital Services Act here in the European Union. I think we’ll see more of things like that. It won’t be confined to social media, but that will be a part of it. I would just say, more generally, I think that the 2020s are going to be a decade of technology regulation, that die has been cast and there’s clearly more coming. I hope that tech companies will step forward and continue voluntarily in many instances to take on more responsibility. I think that’s a part of it. But one of the things we have done is develop what we see as the strategy needed to combat this kind of nation-state influence operations through the internet. And it does require more threat intelligence, the ability to detect these propaganda campaigns over the internet when they’re launched. It does require stronger defense, including just media literacy for people. It requires that we identify ways to disrupt these campaigns in part by just letting people know what we’re seeing. And it may call for some deterrent capability by governments to respond when foreign nations quite deliberately are trying to interfere with their own democracies. So I think we’re going to need a broader strategy that is going to call on governments and the tech sector and civil society to collaborate.

One of the problems that we see is that traditional media, especially local media, are kind of fading out. Is there any way you can help them in their struggle?

I think that that is a key part of it. If you look at our strategy when we published it, we’ve called for the revitalization of local journalism. I think it’s a good time to talk about and explore alternative models for supporting local journalism. What we really have seen is that profits previously going to advertising in journalism itself, like newspapers, moved to digital platforms. The question is, should some of that move back? There have been laws in some countries debated, some countries have adopted them like Australia, and we’ve been supportive of that. We recognize that we’re one of the companies that would end up bearing some of the costs for that. We think it should be done in part with an eye on whether the platforms themselves are profitable. But I do think that we need responsible, healthy, local journalism. I don’t see how we solve all of this unless there’s more local journalism.

How do you feel about Elon Musk taking over Twitter?

Well, I didn’t get a vote. None of us did. I think it’s perhaps a little too early to know how that is going to fully evolve. First of all, I think it’s important to recognize Twitter has played a very important role in recent years in trying to act responsibly, collectively and collaboratively with others to address things like the need to protect children, opening up a data set so people can understand how algorithms can perhaps even inadvertently contribute to extremism online. I’m encouraged by the fact that the headcount reductions for content moderators was less severe for the company as a whole. Hopefully that’s a sign of what’s to come, because I think Twitter is an extraordinarily important global asset. I think Elon Musk is right to think of it as a town square that can play a very important role. You know, I think it’s right that we avoid censorship as the solution, but we do need responsible approaches. I’m hopeful and we’ll just have to see how it evolves.

Ukraine. Do you think this is the first truly digital or cyber war we’re watching?

I think it’s the first hybrid war at a substantial scale. We’ve seen hybrid attacks in other wars, but we’ve never seen anything like this. When I was speaking to the Trilateral Commission group here this morning, I said in some ways it’s analogous to the Spanish Civil War, and most people wouldn’t have a reason to remember what the analogy is. But it was during the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s that aircraft were really used together with ground troops and tanks to create a new technological approach to the conduct of military battles. And then, of course, we saw that it was used five years later when the Nazis invaded Poland. And what we’re seeing in Ukraine is this remarkably ferocious, if somewhat limited geographically, cyber and kinetic war that we do call a hybrid war. So, you see cyberattacks that are separate from kinetic attacks, but you also see them coordinated. We’ve even seen it again in recent weeks when the Russians went to take out energy infrastructure, they often couple it with a cyberattack on the same sites. We are seeing it, frankly, coupled with intensive Russian propaganda campaigns focused not only on Ukraine but on Western Europe and on the US. So, yes, this is a new kind of warfare. So far, the defenses have been holding, at least against what we would think of as more conventional cyberattacks – the efforts to plant malware and take out whole computer networks and the like. So from a strategic perspective, defenses have been stronger than offenses. But it’s early to draw any conclusions because none of us know how long this war will last.

‘I think [the war in Ukraine] is the first hybrid war at a substantial scale. We’ve seen hybrid attacks in other wars, but we’ve never seen anything like this’

What exactly are you doing to support Ukraine? You’ve been doing a lot.

We’ve been doing many different things, but I would put them in different categories. One, maybe the single most important thing from a broader strategic perspective, is actually working with the Ukrainian government and others in Ukraine to actively intercept cyberattacks. So we have our Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center. They identify attacks, and then we use a variety of tactics to thwart them and stop them. That has been quite successful. A second thing, one of the larger ones, has basically been to help the government and municipalities and critical infrastructure and businesses move to the cloud, so that if the computers are destroyed in a missile attack or – as was the case – the Ukrainian government’s data center is destroyed in a cruise missile attack, the data has been moved to the cloud. The Ukrainian government has really moved its digital infrastructure to the public cloud and to Microsoft’s data centers across Europe. And no one even knows which country or which data center a particular service is running in. So that has proven very effective. A third thing we’re really doing is aiding all the humanitarian groups. We’re providing technology aid to the relief organizations, to all of the nonprofits that are either providing assistance in Ukraine or to Ukrainian refugees in other countries. A fourth thing we’re doing is a lot of work to identify the commission of war crimes, including in real time, with satellite imagery that then goes to international organizations, so that when a water tower or a school or a hospital is destroyed, that is recorded, the evidence is maintained and it will be used by the UN International Criminal Court prosecutor or someone like Amal Clooney, who has a team of lawyers. Altogether, we’ve now committed $423 million of aid to Ukraine, a number that would have probably astounded me if you told me a year ago that we would commit that in a single year. But I just think the war necessitates it. We announced in Lisbon another $100 million that brought it over the $400 million mark, it takes our aid forward through 2023 for many parts of this. And in some ways, I think we should consider it not only defending Ukraine, but defending all of Europe and defending all of the democracies of the world, when you look at what’s happening and what’s at stake.

If you project what’s happening in Ukraine in the setting of US-Chinese rivalry or war even, how would the two countries fare in terms of cyber capabilities etc?

Well, the interesting thing about the Russians and the Chinese is that they both are what I would consider cyber superpowers, but in different ways. The Russians have a very well-established ability to penetrate networks, principally for espionage purposes, which they do on a global scale. They also have probably the world’s best capability for cyber influence or propaganda operations, combining conventional human techniques with the use of the internet. And it is worth knowing or noting that they really relied for their conventional cyberattacks on what we would consider to be conventional cyber-weapons and not the equivalent nuclear weapons. And by that I mean they launch malware, it’s designed to move around and across a network, but stay within that network. We would surmise they’re doing that to stay focused on attacks in Ukraine itself and not have it jump across all of Europe or around the world. But they are formidable. The Chinese have a capability that the Russians don’t have when it comes to artificial intelligence and machine learning. They’ve accumulated large data sets over the years through the theft of data that has been widely documented. So they could tailor and target something like an influence operation or even in some cases, cyberattacks with the use of that information. The Russians do not have that kind of AI capability. I think the Russians have a capability that is unsurpassed and you see it manifest itself in the influence operations. In my opinion, it is this combination of social science expertise with technology expertise that gives them this know-how in terms of really seeding and fomenting unrest and trying to put momentum behind it. And, one of the things happening in Ukraine in 2022 is what happened in Spain in the 1930s. Everybody’s studying it. So I think we have to assume that there will be lots of lessons learned and they will be learned by everybody, whether it’s a Western democracy or one of these countries that today is ranked as a cyber-threat or adversary.

Are there a lot of things happening in terms of cyber warfare in Europe that the public doesn’t find out about?

Well, the interesting thing is we as a company have been probably among the most transparent with the reports that we published. We just published another one yesterday with our annual defense report. The individual attacks are not visible because they fail. The difference between a cruise missile that’s shot down and a cyberattack that is intercepted is that the cruise missile is visible and the cyberattack is not. So the public only sees a cyberattack when it succeeds. And what it sees is the impact: We don’t have power or this company stopped operating. So there’s a lot on a day-to-day basis that is not visible. The other things that are not visible are the tactics, techniques and procedures that are being used both offensively and defensively. In the world of cyberattacks, people talk about that. The acronym is TTP: tactics, techniques and procedures. People who are engaged in offensive action have certain techniques, people in defensive action have other techniques. Nobody talks about either because your secrecy is part of what gives you an advantage. So only when a company like Microsoft or someone else comes forward and describes things does the public have an opportunity to catch up. The other thing that I think is sometimes relevant here is in the national security community, in most governments, including most NATO countries, information gets classified. So when a government classifies information, it basically means that the people who work for the government are not even legally permitted to describe what is happening. So in a way that I would not necessarily have predicted a year ago, when we publish a report like we did in June or like we did this week, it actually puts people in government in a better position to talk publicly because they just quote us. And so the opaque nature of cyberattacks, I do think, makes it harder for the public to be informed. That’s one of the reasons that we are striving to do more as a company, to be more transparent ourselves without disclosing the tactics, techniques and procedures that would undermine our own defensive capabilities.

If you take a look behind the scenes, are the people or the systems more important?

Well, at the end of the day, you can’t separate them. Because it’s the people who create the systems and it’s the systems who make the people more effective. It’s been interesting to see some of the uses of AI, including at Microsoft. I think in a sense, there was a milestone reached that we should probably regard as a historic milestone in the development of use of AI. That was Microsoft’s use of it in Ukraine this year. Everybody says: “Oh, a computer just beat somebody playing chess or the Chinese game Go. That’s a big milestone.” I think a more important milestone in the real world, perhaps, was the day when our AI protecting a Russian business in western Ukraine detected a Russian cyberattack and intercepted it and defeated it without any human intervention, before a human being even knew about it. We’re going to see over the next 12 to 24 months, a much broader array of important leaps forward in terms of AI capabilities in all sorts of respects. I always hasten to say we should never want, in my opinion, a day where AI starts a war or launches an attack without a human being in the loop and making the decision. But having AI defend against an attack, I think is something that was important and beneficial.

You’re a global company. Is the deglobalization process affecting you? Does it concern you?

Yes, and yes. First of all, it affects us. It affects everyone. For all practical purposes, we no longer operate in Russia. We had a subsidiary there when the year started that had more than 400 people, and now it has two: a lawyer and a finance person to just take care of the loose ends left. That does concern me because it was the right thing to do, and in many ways, it was the necessary thing to do, given the impact of sanctions, but, there are Russian schoolchildren and there are Russian patients in hospitals that rely on computers to learn or for medical care and the like. And when you start withdrawing technology, you impact humanitarian needs. That’s something that I think we need to keep in mind. We’re obviously seeing more of a decoupling between China and the United States and to some degree between China and Europe. And that’s driven by national security concerns. Yet when I’m on the way to something like COP 27, we’re not going to solve the world’s climate crisis if we don’t work together. So, yes, I think that what’s happening in the world is understandable, but it’s not 100% for the good of the planet either. So, yes, I think that what’s happening in the world is understandable, but it’s not 100% for the good of the planet either.

Let me move to the local stuff. Data centers are moving ahead.

They are moving ahead. A lot of work has been done. I would certainly both expect and hope that if we are sitting down 12 months from now, we could get in a car and drive out and see a large construction site. In fact, more than one. It’s taken a lot of work to figure out how to solve a lot of problems. Zoning laws around the world were not designed for data centers. They needed to be changed. Permitting processes are going forward here in Greece, and it’s very typical of other countries. People figure out how to permit for data centers. But we’re in what I hope are the final months of work to get the zoning permits ready for the final review. It’s an interesting and important process here in Greece in terms of the role that different parts of the government play. But they’re moving forward absolutely. And we’re not just committed, but I would say also excited. I think I’m more bullish on the role that data centers will play in Greece today than I was when I was here two years ago to announce them.

You also have a Skilling initiative. How’s that coming along?

I think it’s making good progress. We committed two years ago that we would skill 100,000 people over five years. Two years in, we’ve passed 35,000, and it’s accelerated in momentum. So I don’t worry about any risk of failing to meet that deadline. What’s really interesting about it is just the number of people we’re reaching. We should all be especially encouraged by the fact that there have been 3,000 people in the Greek government that have gone through our skilling efforts. It’s really interesting that both in the government itself and more broadly, roughly a third of the people that are going through the Skilling program are getting real certifications, and these are not easy to get. So it shows a real increase in the technical acumen and the technical capabilities that are being created across the country. You would be hard-pressed to find many places, many organizations in the world that have skilled more people than the Greek government on technology in the last year or two. That is good news for everybody who lives in Greece, because that technical acumen will then translate into better digital services for people who live here.

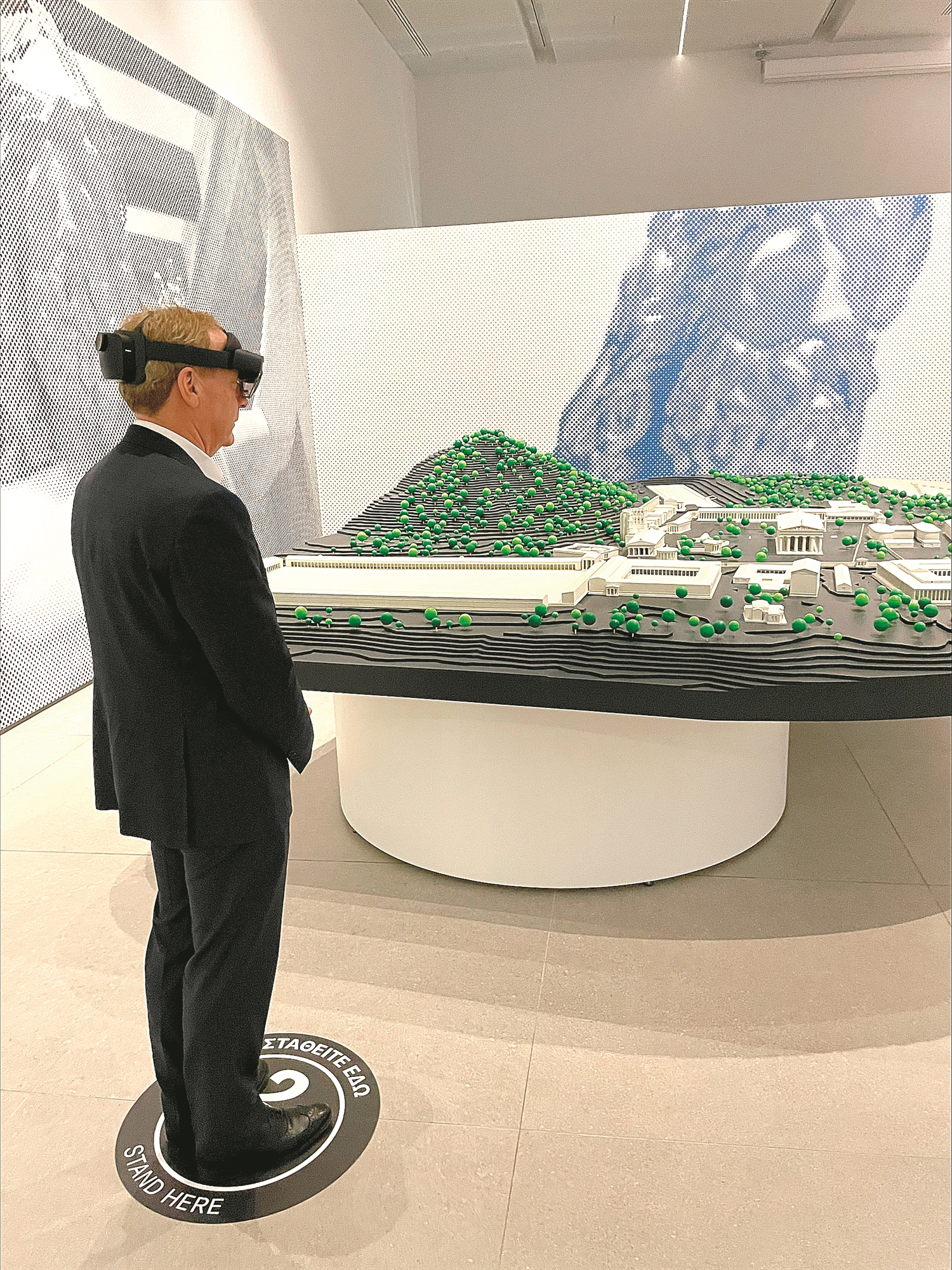

A lot of people are excited about what you’ve done in Olympia. Are you going to do the same in other places?

Well, we are. In fact, we’ll do it in other places in Greece. And I think we’re going to do it in other places in other countries. My next stop this afternoon is to go experience it myself, which will be our first opportunity here in person and in Greece to do it. I think it’s the future for great archaeological tourist sites and for great museums and for expanding access to cultural heritage online. So it clearly meets a need, and the technology will just continue to get better every year. There are many governments around the world that have taken notice of the Common Grounds project in Olympia and they’re interested in it. So our biggest challenge once we leave Greece is not to find things to do, it’s how to prioritize to do the things that will have the biggest impact.

So it will be Marathon or Salamis or…?

Well, I love Marathon myself.

I remember, that’s why I said it.

We’ll see.

How do you see Greece? Because you have been coming here.

We’re looking increasingly at the conclusion of the first quarter of the 21st century. That’s the year 2025. And then as you look to the second quarter of the 21st century, Greece has as much or more momentum than almost any country you see anywhere. If you look at the rate of economic growth and the strength of its foundation, I think you always have to look at both of those things together. You look at the structural changes that were made, the reforms that were instituted, the use of digital technology, the way Greece used technology to get through the pandemic, the lessons that were learned. I think you see something that’s quite remarkable here. And, you know, it’s easy for people to say, “Well you went down so much that, of course, you were bound to come back up.” And while there may be some truth to that, this goes far beyond that. And then add to that, democratic freedoms, creativity and political stability. It’s easy for people to look around the world in 2022 and say democracy is under threat and democracy is not as healthy as I think we should want it to be in much of the world. And yet, Russia started a war that it cannot win and does not appear ready to exit. Iran is inflamed in protests. China is still sitting in the middle of Covid. So in a way, this hasn’t been a great period of time for any political system or any part of the world. And when you travel as much as I do, frankly, what is the most remarkable thing about Greece when you come here is to see how well it’s doing compared to most of the world. Now, we’ll all have an election next year, and one should hope for, again, a stable political framework that moves forward. But I see all kinds of cause for optimism that that will be the case.