Equitable distribution of vaccine is key

The Columbia University professor says it’s going to be a couple of years before we possibly relax into old habits

Covid-19 mutations are a major concern to the scientific community, according to Jeffrey Shaman, professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University. In this interview with Kathimerini, Dr Shaman speaks of the urgent need to extend the vaccination programs not only in the US and Europe but also the developing world, because if such large shares of populations continue to remain unvaccinated, new virus mutations will make a return to normal even harder.

Dr Shaman, what’s your latest update on the Delta variant, and what is the biggest threat associated with its spread?

Well, the Delta variant appears to have two properties that make it problematic. The first is that it’s more transmissible: It’s more transmissible than the original emergent variant that came out back in probably late 2019 and it’s more transmissible than the Alpha variant, which was the UK variant that we heard about and were concerned about for a good time. But it also has properties that are like the South African and the Brazilian variants and it seems to be able to cause breakthrough infections and reinfection. So it has the property of what we would call “immune escape.” And that immune escape doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to cause severe illness, but it means that a lot more people are in play and are able to pick up the virus and pass it on to others who may have never been exposed to it or never been vaccinated. And it’s those individuals who are at risk of severe and critical illness.

Do you sense that Delta will be the dominant variant in the US and Europe soon?

I think so. It already is in the UK and in quite a number of parts of the world, and it seems to be growing exponentially in other environments, such as the rest of Europe and the US. Right now it is the variant of leading concern, I think, because of these properties. Unfortunately, it doesn’t mean that another variant won’t come along that will have even more aggressive properties that we’re going to have to contend with.

What’s the outlook for the next few months or the fall? Do you think a fourth wave is inevitable?

I think we’re going to be seeing a fourth wave, yes, I do. But the thing that is maybe a little bit of a silver lining is that if a population can get vaccinated to a high level, the amount of severe illness associated with it, the rates of hospitalization and deaths are likely going to be lower. There are some really interesting statistics about this right now. The UK, which has had a lot of vaccination, is having an explosion of cases with the Delta variants. But mortality has not increased very much at all. It’s not the same as in other countries that are not as well vaccinated. And it really emphasizes the need to get the vaccines distributed equitably all around the world. I know Greece has hit 9 million doses at this point. And you really want to pick up the pace on that, because studies that have come out recently in the last few weeks show that people who have been vaccinated are not being subject to severe and critical illness at the same rate as those who are unvaccinated. They’re quite protected against it. So even though they might get a mild case, they’re not going to wind up in the hospital.

And what about social distancing and masks and other measures? Should we continue wearing masks indoors and outdoors even if we’re vaccinated?

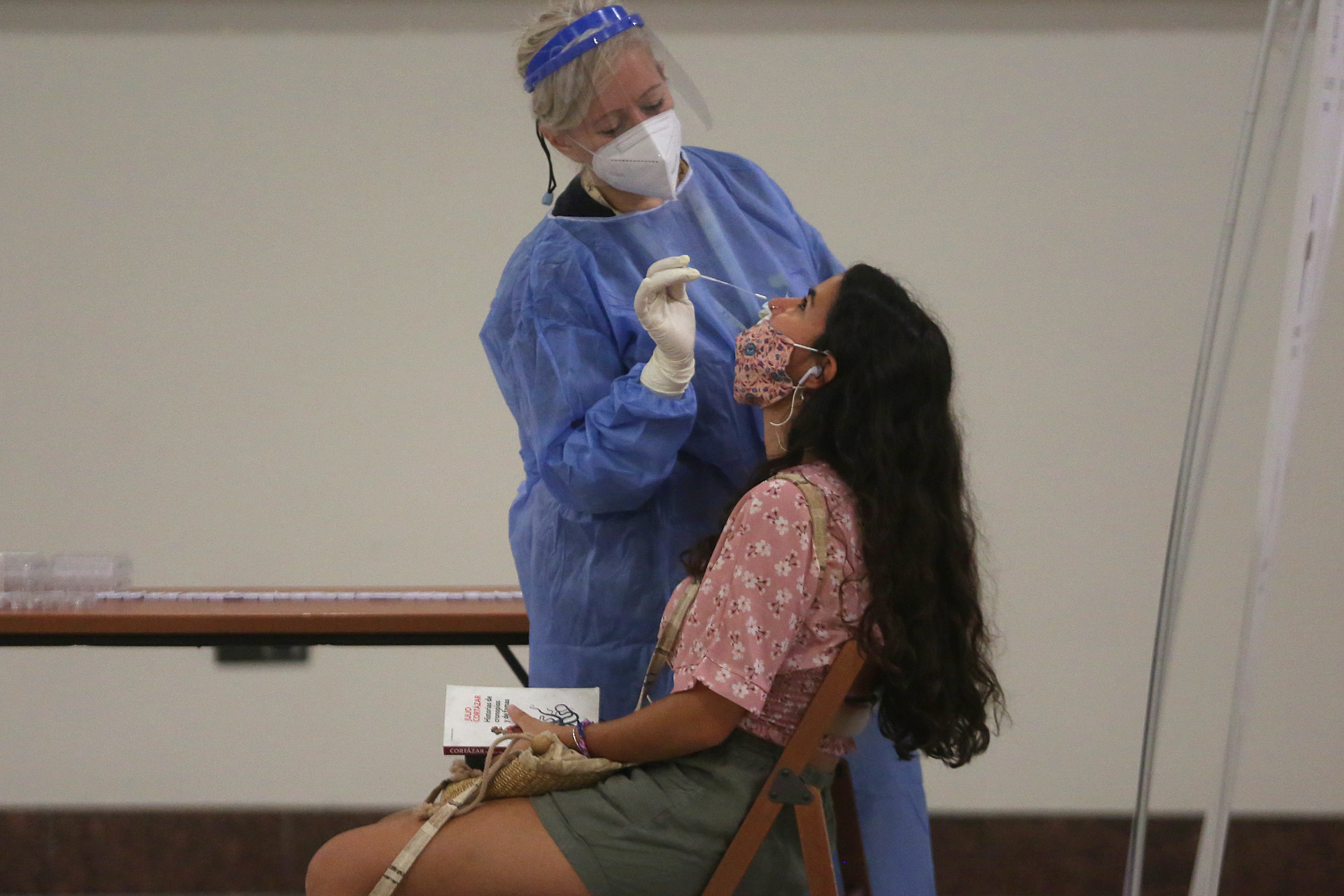

You know, in some sense, it’s a complicated issue in that people want to take the masks off. They want to stop with the social distancing. It’s been a year and a half and we’re all exhausted from it. But the reality is you really want to look at the larger population and you want to understand that masking and vaccination and social distancing are not just about an individual’s own health. They’re about the collective health of the people around you. And even if you’re vaccinated, you do have some risk of picking up the virus and being able to transmit it to others who might not be vaccinated, even though your risk is less and even though your risk of severe illness is much less, you still can be this vector, this person who transmits it on to somebody else, who gives it to your grandmother who’s not vaccinated or to an immunocompromised friend or to somebody you’ve never met, who you happen to pass in a store or a restaurant or something like that. So, it really is advisable to continue with these non-pharmaceutical interventions, social distancing and masking for as long as possible, because the aim is to get the vaccine in as many people’s arms as possible before they are exposed to the virus. So, if only 20 percent of the population is vaccinated fully at this point, you really want to get that number up to 60%, 70% if possible, even higher, of course.

By now I guess there are millions of people infected with Covid-19. What is the best way to achieve herd immunity? Is it a combination of vaccinated people and those who became ill as a result of the virus? It seems we’re not sure how long those who contract the virus remain immune to it afterward.

Yeah, you know, and this is something that we’re really not fully understanding at this point, you know, the question is how long is immunity in place. And, as you said, people who have been previously infected may actually be subject to some sort of reinfection. In that sense, herd immunity may not mean something really the way we would hope it would. You know, with some diseases like chickenpox, a person gets it and that’s it. They’re done. They’re not going to get it again in their lifetime. On the other hand, you have diseases such as the flu, which people get over and over again, because of a combination of immune processes and the fact that the virus is always changing and there are multiple lineages of it in circulation at any one time. Unfortunately, coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of Covid-19, is actually more like the flu than like chickenpox. And it’s going to be a risk that we’re going to have new variants emerge that are capable of causing infection for people who have already been vaccinated or already been infected; and that the immunity that we get either from a prior infection or from vaccination may only be temporary. And we may need additional vaccinations over the years. These are things that we don’t know fully how they’re going to play out right now. And so it’s unfortunately something that we’re going to learn over time, really to get a good sense of it.

Still, there is a number of people who are refusing to get vaccinated. Even so, President Joe Biden is proposing door-to-door efforts to convince people. What is the best way to convince them of the necessity to get vaccinated?

It’s a very, very tough question because there are people who have sort of embedded the idea into their belief system that vaccines are potentially harmful, that they’re more dangerous than the virus itself, that they are not necessary or even that they’re a plot by the government to harm them. And overcoming those different obstacles, those different ideas and thoughts is very difficult, and it requires a lot of effort. It requires education, it requires outreach. It requires pushing through people in the communities that they might trust, co-workers, family members, people in their church. Things of that nature is the way you have to start to reach people to get the vaccine numbers ticking up. But it’s very hard once you get the people who are eager to get the vaccine or willing to get the vaccine – it really slows down. And if you want to hit some number like 70%, you know, in my country, the United States, it’s proving to be very challenging in some populations.

Are you worried about the fact that lower income countries have been much harder hit and do not have access to vaccination? Is that a threat for more variants in the future?

That’s a threat in multiple ways. It’s highly inequitable. And it’s something that we need to remedy. We need to get the vaccines distributed broadly. This is not something that should be the purview of developed countries alone. Everybody should have access to the vaccine and it would be nice to get them distributed and administered in the most remote portions of the world to protect populations there. But as you say as well, if we leave portions of the globe unvaccinated, those populations are going to pass the virus from person to person, and it’s going to increase the opportunities for new variants to come about, variants that could render the vaccine less effective or even useless in a worst-case scenario.

And to that end, do you sense there’s a new normality, that we have changed our lifestyles? I mean, masks, social distancing, no handshakes, teleconferencing, the end of business travel, etc. I mean, is what we remember in 2019 now a utopia?

I think it’s going to be a couple of years before we possibly relax into old habits. I think we’ve also learned some things here and there’s some old habits that we may actually do away with. And we hear a lot about businesses changing to hybrid models and being more flexible, some of them about remote work and such. I think you could have a mix. I think there are people out there who never took the pandemic seriously and never changed what they did in their lifestyle, regardless of what the government told them to do. I think you have others who have been really affected by it and concerned by it. We’re going to be very cautious and not want to return to the old normal until things really have stabilized. And they’re going to need another year or two before they’re convinced that things are really safe. I think the reality is it’s going to lie somewhere in between and we’ll see over the next year or two.

That leads me to my final question. What’s your best-case scenario and what’s your worst-case scenario for the next couple of years?

Well, the best-case scenario is that we produce a lot of these vaccines. We get them distributed and administered. They prove to be highly effective. And we naturally need a cycle of possible booster shots to give that we produce and are able to distribute broadly to keep people protected. And then people are only subject to mild reinfection. The absolute best case is that even if this virus is reinfecting people, it’s tending to cause very mild outcomes. People don’t wind up in the hospital and mortality rates are very low. And that’s something that we can live with if it becomes something like flu, H1N1 or one of the endemic coronaviruses, which would be even better, then it’s something that’s really not that disruptive, that we can live with. The worst case is that we get these variants that appear that render the vaccinations and prior infections naturally acquired useless and that cause severe disease that continues unabated or episodically and cause these really devastating, disruptive ways. That’s the worst case.