Fifty years after the Metapolitefsi

To begin with the word itself: Let us remember that the first “Metapolitefsi” (the restoration of democracy) had already taken place before the Junta’s fall, in 1973. Georgios Papadopoulos had gone on the radio to hail the “revolutionary Metapolitefsi of June 1 [which] inaugurates a new phase in the national and political history of Greece.” This was his way of denoting the Junta’s abolition of the monarchy and his own ultimately unsuccessful liberalization effort. One year later, people began to use the word to refer to the Junta’s collapse. When, in the autumn of 1974, Konstantinos Karamanlis talked about the “Metapolitefsi” moment, it had a clearly positive sense. A [Greek Communist Party, or KKE, newspaper] Rizospastis editorial around the same time, however, talked about “two months of the Metapolitefsi having clearly shown the prevailing power of ‘reactionary forces’” – meaning this was not the genuine overthrow of the old regime: It was only a Metapolitefsi. The term thus possessed at the outset an inherent ambivalence.

For many people it always connoted specifically the transition of 1974-75. As time went on, however, its range and its end-point shifted. Commentators in the PASOK camp in the 1980s saw the Metapolitefsi ending with their historic victory in 1981 as if the triumph of Andreas proved that an ambiguous transition was over. Later writers have claimed that it ended only in 1989, or 2004, or 2015 -– or maybe it has never ended at all. Today we hail “Fifty Years of the Metapolitefsi.” Should I translate that to mean half-century of the Metapolitefsi – or do I mean since the Metapolitefsi? The ambiguity continues, reflecting our subconscious reluctance to lay claim to too much, to see democracy as more settled than it really is, especially as its prospects around the world darken.

A minority view from the start argued that the fall of the Junta had changed nothing – that as the 19th century French journalist Alphonse Karr wrote after the revolutions of 1848, ‘Plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose.’ This view was especially associated with the extra-parliamentary Left. Following its killing of CIA station chief Richard Welch, November 17 issued a statement claiming that there was nothing to choose between the “fascism” of the Junta and the “neo-fascism in parliamentary disguise” of 1975. Many others on the Left shared those suspicions at first, frustrated by Karamanlis’ gradualism and by the limited purge of Junta supporters, but although the revolutionary Marxist critique of parliamentarism never vanished, its appeal dwindled as one free election followed another.

The view, though, is worth engaging with, if only because it is true that no break in politics is ever total. One objection to it is that insofar as it implies the transfer of power was some kind of conspiracy, it gets things back to front: Conspiracy there was, to be sure, but it came at the start of the Junta, not at its end. Another is that it wrongly describes the Junta as fascist: Rather, it originated within and reflected the authoritarian culture of the military officer corps, and perhaps because of this it never made the transition to one-party totalitarianism that Italian Fascism made in 1926 or the Third Reich around 1934. The Junta was also comparatively short-lived – just seven years in charge compared with Benito Mussolini’s two decades or General Franco’s three decades plus – and it faced international headwinds because it emerged at a time when the memory of a war against fascism remained fresh throughout Europe. For all these reasons, by 1974 it had still put only shallow roots in Greek society. Even so, it was not easily overthrown (dictatorships rarely are) and its downfall came – as it did for the Third Reich and Italian Fascism – only through defeat in war.

In my own view, the summer of 1974 was a political crisis in the original sense if ever there was one: That is to say, it was a time when political decisions counted and had enduring effects. But it was not Zero Hour and there was more continuity in the transition than there was, say, in Germany in 1945. The Colonels from the outset saw themselves as a parenthesis and so the question of transition had been posited from the outset. Even if they could never quite bear to give up power, or to set a date when the troops would return to their barracks, they were always unwilling to declare their own permanence. Their abortive 1968 constitution was never implemented of course; but the interesting question is why they felt the need for it at all. As for their republican Metapolitefsi of 1973, this was one action of theirs Karamanlis was inclined to accept. This is why when his constitutional act of August 1 temporarily restored the 1952 constitution, it was with the exception of monarchical rule. In his memoirs, the other Constantine [then king of Greece] describes his shock when he learned in exile of what he terms Karamanlis’ “clear constitutional deviation following in the footsteps of the Junta.” In a strictly legal sense, he was not wrong.

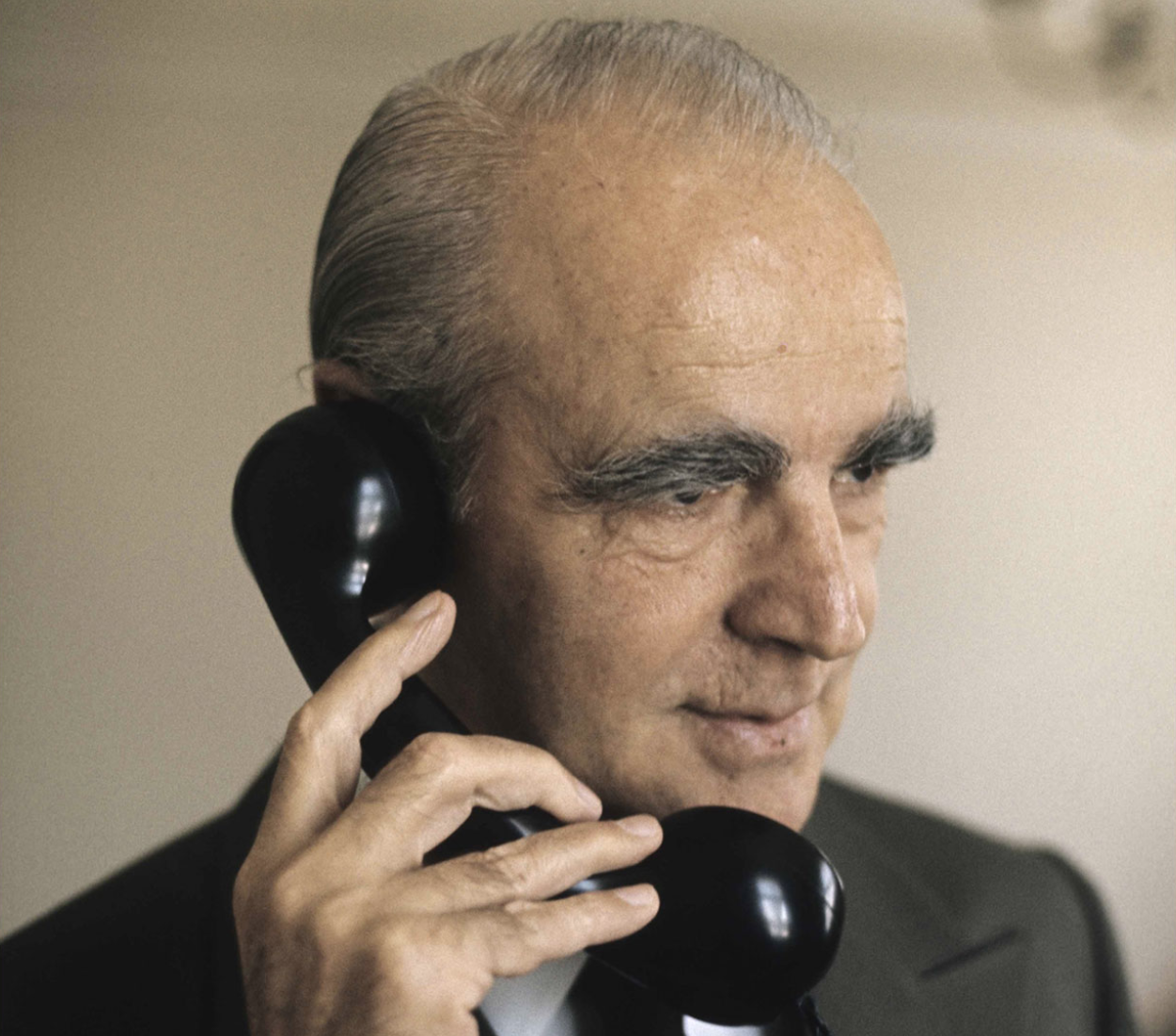

Karamanlis’ decision on returning from Paris to allow himself to be sworn in as prime minister by the Junta’s last president thus reflected a certain ruthless pragmatism: It might have suggested a nominal acceptance of the Junta’s constitutional legitimacy but General Gizikis was, after all, a man on his way out who could be tolerated as a figurehead precisely because of his weakness. Yet behind this pragmatism was Karamanlis’ understanding – one senses here the importance of exile as a crucial learning experience for him as well as for other political leaders of the Metapolitefsi – of how radically the political landscape of Greece had changed and was required to be reshaped. For it was emphatically not just the Junta whose seven-year legacy needed to be buried. The country had been living with a compromised constitutional order for a much longer time than that – an order based around the royal court, the army and a closed world of “nationally minded” politicians. One signal of his realization of this was that Karamanlis abandoned his old party, ERE, to fight the elections of November under the banner of the symbolically named New Democracy.

Not everything was a matter of skill or political genius to be sure. Those tasked with the restoration of democracy enjoyed a certain amount of good fortune, notably in the way the voting went: The unassailable and overwhelming majorities in late 1974 both in the national election for New Democracy, and in the referendum against the return of the king restored the credibility of parliamentary government and paved the way for the new republican constitution the following year. The preconditions for a radically changed political environment were thus put in place: The army was returned to the barracks, the king was consigned to history and the Left was brought back into the mainstream of political life. PASOK’s triumph in 1981 was perhaps the ultimate illustration of the scale of the change and the moment when many on the Left began to believe it was real.

Once KKE had been legalized, neither anti-communism nor royalism played the role on the Right they once had: The nature of the Right was thus fundamentally altered. But so too was the Left. Marxism as a language and culture of political mobilization won ground after 1974 much more than communism itself did: It was not KKE that gained the most but PASOK, a party not so historically connected to one side in the civil war but promising a more capacious social reintegration. The changes in the realm of political reconciliation wrought by this broader Left endure to this day along with the transformation of civil and family law, the consolidation of human rights, the expansion of higher education and creation of a nationwide health service. These years also saw an extraordinary cultural and intellectual efflorescence in the arts, theater, publishing and the universities. In the early 1980s, Greece was a country that was, as it were, “thinking with history” to debate and move beyond the cleavages of the 1940s in a fashion that had simply not been possible earlier. In short, it was in the Metapolitefsi that the country overcame the polarizations of its past.

Over the last half-century Greece has espoused a democratic politics that by and large works across the ideological spectrum and produces generally durable governments of all stripes. My basis of comparison is not some theoretical vision of political modernity but the world around us, as it is now, and as it was in Greece in the past. Greece’s parliamentary tradition, as Nikos Alivizatos has usefully reminded us, stretches back to the 1840s. Nonetheless, this half-century has been the first period in its history in which the average life-span of a government has exceeded two years. (For much of the 19th century it was under one.) There has been a transformation in civil-military relations that is not, for various reasons, capable of being easily reversed. The monarchy has become a dead issue. European institutions and participation in European integration certainly fostered this democratization process. But overall the consolidation of new political norms after 1974 strikes me as primarily the result of discussions and decisions taken in Greece.

The Metapolitefsi not only changed Greece’s relationship to war; it also brought to an end Greece’s ancien regime. What replaced it was a new form of governance

International and global forces have had a much more decisive impact in the realm of social and economic change, though I think that was true everywhere from the 1970s onwards. In postwar Western Europe, the consolidation of welfare states preceded the liberalization of international trade and the globalization of finance by several decades. But it was only really from the 1970s that, starting under first under New Democracy and then accelerating massively under PASOK, Greece expanded the size of the public sector, nationalizing industries, creating a public health service, and increasing public education. These trends responded to social expectations but they also expedited, and were accompanied by, clientilism on an unprecedented scale: It is not coincidental that memberships of the main political parties skyrocketed in those very years too. Theories of patron-client relations that see Greece as a textbook case from way back in the mid-19th century may lead us to overlook the exponential rise in the interpenetration of state and party that took place from the early 1980s onwards. Tax revenues increased significantly but the growth in public spending easily outstripped what they brought in: The basic numbers are familiar to everyone.

The fiscal implications would have been problematic in the best-case scenario. But to make matters worse, these trends were taking place at precisely the same time that the country was participating ever more deeply in the project of European integration. Had this been the 1950s or 1960s, it might have mattered less and the drachma could have taken more of the strain. But by the 1980s, Europe’s leaders were prioritizing monetary alignment as the route to closer union and demanding an unprecedented fiscal discipline; and by the late 1990s globalization had changed the rules of the game. In 2010, as the debt crisis worsened, the implications became clear. Greece could theoretically have chosen to abandon the European ship but in fact there was little stomach among its electorate for that.

Thus we arrive at the two basic ways the Metapolitefsi is conventionally construed: [a] as a narrowly political-constitutional achievement, which is generally (and reasonably) regarded in highly positive terms; and [b] as the catalyst for a wider socioeconomic transformation of the country, where the record has been more mixed.

By way of conclusion, let us step back for a moment. Greece has not been in existence as an independent state for very long: Indeed we can encompass the span of its history in just two lifetimes. Apostolos Mavroyenis was a doctor who was born on Paros around 1792, a member of the illustrious Phanariot family. He fought in 1821 and at his death at a very respectable age in 1906 he was reputedly the last survivor of the War of Independence. The year before his death was the year that the future politician Lambros Eftaxias was born into a wealthy Athenian family: Karamanlis’ friend before the Second World War and his backer after it, Eftaxias himself died at a great age in 1996. These two lives – Mavroyenis’ and Eftaxias’ – are all that are needed to vault us from Ottoman times to our own.

When Mavroyenis was born, there was no Greece and no politics in the modern sense at all: The very idea of a nation-state was unknown and Athens was an Ottoman backwater. By the time of his death, Greece was a well-established independent polity whose boundaries were being constantly enlarged through war. Territorial conflict in Mavroyenis’ world remained a normal and even positive thing, for without fighting Greece – and many other countries – would never have come into existence. This attitude, which explains the prestige of the officer corps and the weight of the army in politics, did not immediately change after Mavroyenis’ death, not even – I think – after the Asia Minor catastrophe. A key significance of 1974 is surely that it marked the moment in which this very long tradition of irredentism finally ended in Greece – its legacy visible even now in the ongoing tragedy of Cyprus. In short, Greece is today, in a profound sense, a postwar – μεταπολεμικη (if I can term it thus) – country.

When Lambros Eftaxias was born in 1905, Greece remained largely rural, illiterate and incapable of feeding itself. But Athens as the national capital already enjoyed a decades-long tradition of parliamentary politics. Formally, it was governed through the monarchy and dominated by a few European Great Powers. But in its day-to-day workings the country was in the hands of a specific elite – let us call it for want of a better term the μεγαλοαστικη ταξη [middle class] – whose members ran key institutions such as the university, the banks, the ministries, courts and diplomatic service. This was the class that had come into existence in the middle of the 19th century and into which Eftaxias was born. From 1932 until the coming of the Junta, he held the same parliamentary seat in central Greece that his uncle had represented since the 1880s: It was thus in his family for 80 years. For Eftaxias and men like him, politics were regional and familial first and about party second. Both in the διχασμος [National Schism] and in the civil war, it was clear which side Eftaxias was on; at the same time, the real core of his ideology, if I had to sum it up, was neither monarchy nor anti-communism but more basically, the protection of the αστικο καθεστως [urban status]. Run by this class with this outlook, Greek politics possessed – below its turbulent surface – a remarkably stable sociological character for much of the late 19th and 20th centuries. It was – again – 1974 which marked for reasons I think we do not yet fully understand the end of the μεγαλοαστικη ταξη as a political force. The Metapolitefsi thus not only changed Greece’s relationship to war; it also brought to an end Greece’s ancien regime. What replaced it was a quite new form of governance – based around publicity rather than discretion; highly centralized party machines, not notables.

The political institutions of the Metapolitefsi have proved to be robust, capable of surviving even the repeated crises of the last decade and more. Their challenge in future is to show they cannot only survive but also tackle the widespread suffering these crises have left in their wake – their impact on the education, outlook, health and appalling job prospects of young Greeks perhaps above all. I am increasingly struck by the generational character of the Metapolitefsi: If it was Karamanlis’ generation that oversaw it, it was the one below him that reaped the benefits. Now they are themselves giving way to those below them, those between 15 and 50, who have no memories of the years of the dictatorship and have their own concerns and struggles: a growing income inequality which threatens many with immiseration; a pace of technological change that is destabilizing work patterns; mass migration from across the Mediterranean that challenges nationalist models of community; regional conflicts in the Black Sea and the Middle East; and perhaps, above all, global warming and environmental degradation. One constant from 1821 until now has been the remarkable resilience of Greek society in the face of major upheavals but it would be unwise to count on this resilience alone in future. Let us hope that future politicians can rise to Greece’s current challenges with the skill and the wisdom and the sense of history that their predecessors displayed 50 years ago.

Mark Mazower is a historian and writer, specializing in modern Greece, 20th century Europe and international history. This is a speech he delivered at the “50 Years of the Metapolitefsi” conference in Athens.