Competitiveness in Australian higher education: Lessons for Greece

A recent review by The Guardian of universities makes reference to how the “Australian lesson might spark much-needed change” and raises questions on whether politicians also need to answer questions like, What happens if a university goes bust? An independent review of universities was commissioned by Australia’s Labor government as securing the sector’s future presents numerous challenges.

Public debate has also opened in Greece regarding the government’s proposal for the revision of article 16, par. 5 of the Constitution, which prohibits the establishment of private universities, and is accompanied by intense political confrontations. Much has been written about the Greek government’s decision to proceed with the abolition of the state monopoly in higher education by allowing the operation of private universities/colleges. This has included comparisons with other countries, including Australia. Most seem to be inaccurate and lacking depth, and a case in point are statements such as “In Australia there are 2-3 private universities just as unknown and of low quality as in the above countries. Australian Authorities ruled it a “failed system.”

Australian public universities are set up under their own legislation, accredit their own courses and degrees, and do both teaching and research in a range of fields

The truth is that Australia is home to 41 universities, with 37 public Australian, three private Australian, and one private international university. Most universities have more than one campus (including international) and provide a range of study options. It must be stated here that Australian universities are high ranking internationally (in comparison to Greece) which acts as a barrier to entry for foreign universities in a competitive environment.

Furthermore, Australian public universities are set up under their own legislation, accredit their own courses and degrees, and do both teaching and research in a range of fields. But the total in the Australian higher education system is made up of around 170 higher education providers. These private providers are registered by the national regulator, Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) and provide study programs for both domestic and international students. I personally happen to serve on academic boards of such providers and I am fully aware of the stringent TEQSA requirements.

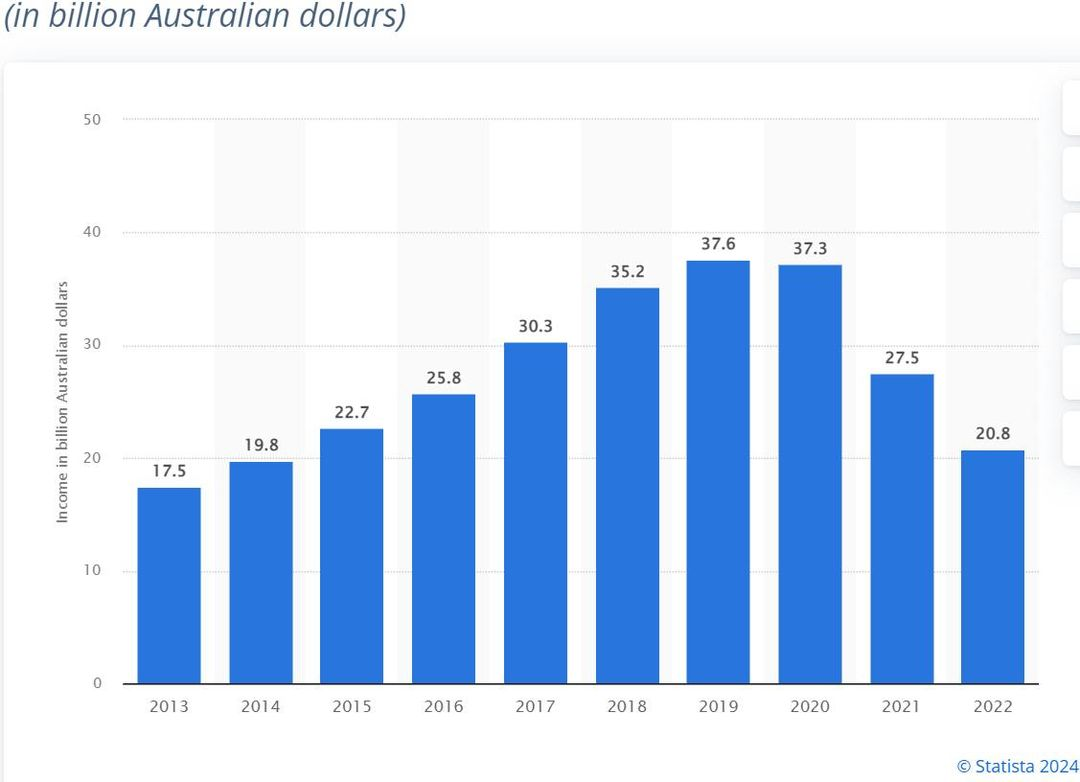

Over the years, Australian public universities have developed an international orientation and have been a substantial source of export income from international education activity as shown in the table below in billion Australian dollars, from the financial years 2013 to 2022:

The decline in the latter years is attributed to the pandemic, changes in some Australian Policy settings, and the fact that higher education standards are on the rise in the Asia–Pacific region.

For Australia, this year marks almost 35 years since the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) was introduced by the Labor government under the leadership of Bob Hawke, effectively bringing to an end the short-lived period of free education that began in 1974 under Labor Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam. Today it is known as the student HECS-HELP loan that allows students to pay for their studies when they attend university or an approved higher education provider. This is in sharp contrast to free education in Greece. The HECS-HELP loans from the Australian government are tuition fees that are paid directly to the institution of the students’ enrolment by the government. Once students graduate and earn a certain amount of money, they need to start paying back through the Australian taxation system when their income reaches a certain threshold.

This acts as a pressure point for Australian students to expedite their studies and for higher education providers to ensure that their programs meet quality standards. In comparison, free education in Greece is associated with very low graduation rates as well as an exodus of Greek graduates to other countries (brain drain) that derive a benefit of their services at the expense of Greek taxpayers.

Finally, this model has served Australia well and improvements are always under consideration as noted in The Guardian’s article. The establishment of private non-profit universities is under way in Greece (as a long overdue reform) whose intent is to contribute toward a competitive landscape in higher education. This may not happen, but the possibility of private universities entering the market has some “disciplining” effect on the behavior of public universities already present in the market in comparison to a lack of potential competition being small when market entry barriers are high as has been the case in Greece. Attempts to compare the situation in Greece with other nations must be comprehensive and not superficial, especially from academics.

Dr Steve Bakalis is an expert in international business education and management, has worked with the Australian National University, the University of Adelaide, and in administrative positions in universities in Asia–Pacific and the Arab States of the Persian Gulf.