A macroeconomic dashboard to keep Greece aloft

It is difficult to make progress if you cannot measure it. Some things can’t be quantified, such as love, happiness or beauty, but in macroeconomics, measuring things is very important to get an idea of what is going on. Sometimes people have complained to me that macroeconomic policy making is about numbers and not about people – the public does not understand what is being done and why.

This is a problem, because one way to describe macroeconomics is as a large amount of numbers that describe what a large number of people are doing. So, yes, you have to know the numbers, because these are not empty dead spots, but rather live pieces of information. Following time series tells us something about how large numbers of people are changing their collective behavior, and how they react to impulses, shocks and government policies that impact the economy.

The numbers, of course, have to be good numbers. Not the numbers that we would like them to be, but the actual truthful numbers. In some countries, such clean hard numbers are difficult to come by. Some political systems find certain numbers embarrassing for the country, and therefore they change them a bit – to do the public a favor, I suppose. But this is a form of fooling yourself, and that can have disastrous consequences.

Consider the following metaphor. The prime minister is really a captain on a jumbo jet, let us say a special Boeing 747. The regular Boeing 747 can hold 500 people. But the special jumbo jet that the prime minister is flying has 10.5 million Greek people in it. He is in charge and coordinates what goes on during the flight that he pilots for four years, with the possibility of repeating it for another four years.

Now, the PM has in front of him a large dashboard with innumerable dials and instruments that all display numbers. These numbers change all the time and he needs to keep an eagle eye on what they are telling him about things such as ground speed, altitude, engine thrust (“Should I push in a bit more fuel to speed things up?”), distance to target, and even cabin temperature etc.

Now, let us say that there is some turbulence along the way and he sees some numbers that he does not like. Will he ask his engineers, particularly the minister of finance and the governor of the central bank and the president of his statistical institute to change the dials a bit (“just a small recalibration”) so that he no longer sees those disturbing numbers? Or will he accept the numbers as provided and then adjust policy? Will the people of Greece in their magical jumbo jet arrive safely if the dials are tinkered with to please the politicians, but the numbers are fake?

So, a good set of numbers chosen for specific reasons with theoretical and empirical relevance is essential for running any economy. I would like to present just a few of these numbers that I would keep my eye on if I were asked to help bring the people safely home.

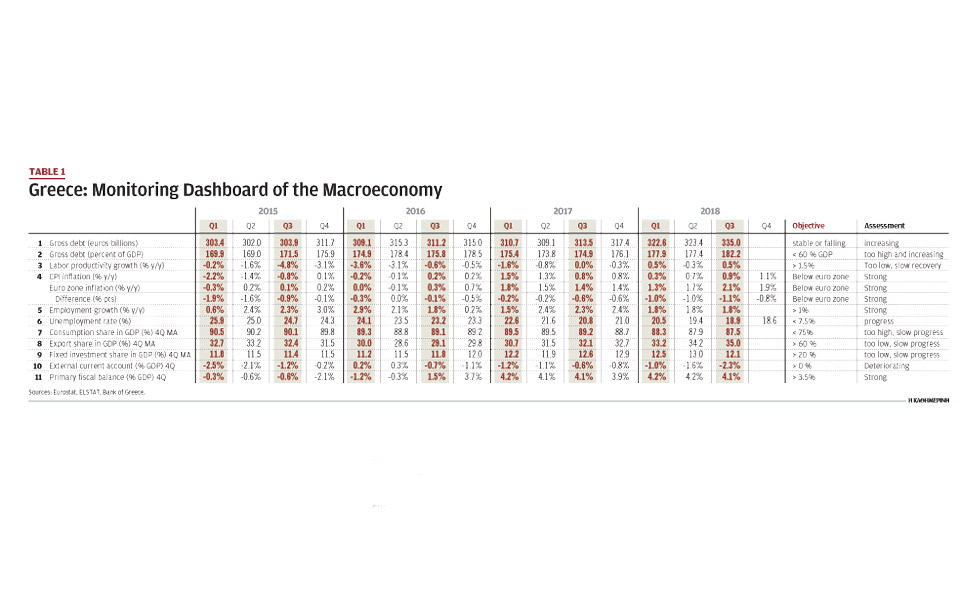

Table 1 presents a small dashboard, a sample, of time series that are worth tracking and monitoring for Greece. The numbers are presented in the form of time series, so that we can see how they change over time, and, importantly, I also include an aspirational target that I believe would make for a reasonable objective to achieve through policy. How to structure policy to achieve these aspirational targets is of course where the art is separated from the science, but that is another long story. Here we are presenting selected numbers and a benchmark to see what is the distance between reality and aspiration. We can walk through each of these numbers in turn:

1. Gross debt: Measured in billions of euros. Greece needs to (at least) stabilize the debt, be it with a fiscal surplus or with asset sales. This will take time, as I discussed in Odysseus’ Plan. Recent experience has been that the stock of debt continues to increase even though the government says it is running a fiscal surplus. This variable needs to be watched and an explanation for its increase remains due.

2. Gross debt ratio to GDP: If Greece starts growing again, and sound fiscal policies are on track, the debt ratio ought to come down. The distance from target is very large so discipline and patience are important. Not only has the debt been increasing in euros, but the debt ratio has also been increasing, even though growth has resumed. This is a red flag. An explanation is due.

3. Labor productivity growth: This is measured over the same quarter a year ago. Greece is now making progress, as growth has restarted, pulling up employment growth in its wake. The target for productivity growth is 1.5 percent a year, and the country is not yet there. This is an important structural variable, so important to watch.

4. CPI inflation: This variable is important to strengthen price competitiveness in the economy. Greece did damage to competitiveness in the boom by having domestic inflation running on average some 100 basis points higher than in euro partner countries using the same currency. That is not sustainable and we know now what the results of such outcomes are. Greece is now doing much better, with inflation somewhat lower than in euro partner countries. This will improve competitiveness over time, if sustained. Like getting debt down, regaining competitiveness is also a slow and grinding process. It requires discipline and perseverance. Important to watch, and therefore deserves to be on the dashboard.

5. Employment growth: If industrial economies with slow demographics can steadily make employment grow by 1 percent, then they are doing well. Greece has to burn off a large pool of unemployment, so somewhat higher growth rates would be ideal to get unemployment down: There is good progress on this front in Greece at the moment.

6. Unemployment rate. This is still far too high at around 18 percent of the labor force, but the unemployment rate is coming down. Recall that if employment growth is high but unemployment is coming down slowly, this may mean that the labor force is growing through increasing participation. In the labor markets three variables interact simultaneously: employment, unemployment and participation. One wants to see a steady decline in unemployment.

7. Consumption share in GDP: We measure 4 quarter moving averages to smooth over seasonal patterns in the quarterly data. Consumption remains very high in Greece, well above industrial country peers. Hence, there is some justification, at least temporarily, to weigh the tax burden to indirect taxes. But watch the distributional effects, and assist those at the lower-income echelons that may be disproportionately hit.

8. Export share in GDP: Domestic demand is too strong, structurally, and the economy is not open enough. Exports for a “small open economy” should be much higher than what they are in Greece. A deep discussion is necessary to find out why Greece does not have large enterprises that have a name in international markets and can operate with scale. It is difficult to become an exporter and capture foreign market access if the firm is small, unless a niche player. Greece’s industrial structure is unusual and suggests that something is wrong in the product markets and in market regulation for well-contested domestic markets.

9. Fixed investment share in GDP: The need for fixed investment depends on real growth and the starting size of the capital stock. Slower-growing economies need less investment, but Greece still needs to build its competitive international productive sector (see point above), so investment should lead growth. In an earlier Note, we discussed that consumption seems too high, and exports and investment too low. These are crucial structural indicators for the economy. They cannot jump overnight, so, again, this requires discipline and perseverance.

10. External current account: I propose that Greece does not try to grow through boosting domestic demand (i.e. consumption) for the time being. A swing to output growth induced by a strong net foreign sector would constitute needed rotation in Greece’s growth pattern. This implies that a current account surplus can be well defended, even though this should not be a permanent target of policy, because that would interfere with the management of global imbalances. If resources can be reallocated to the tradable sectors of the economy, Greece’s recovery will be sounder and longer-lasting.

11. Primary fiscal balance: Greece deserves credit for the strong primary surplus. The question is now one of structure of taxes and expenditures. Is the primary surplus sustainable from a socioeconomic point of view? The government should aim to smooth the sharp edges of acute distortions in taxation, and refrain from boosting structural expenditure. Bringing down structural expenditure is a powerful and sustainable debt reduction strategy. Benchmarking with other European countries to see where Greece spends more than partners provides insight into options for fiscal reform.

Closing thoughts

This is the last Note for Discussion – we have discussed 25 of them in all. We have traversed a large arc from birthrates and demographics to the structure of aggregate demand and fiscal policy, and lots in between. The economy is a general equilibrium where all variables are connected and move simultaneously. That makes policy making difficult, but also fascinating.

Greece has emerged from a very difficult recession. Much work remains to be done. It would not be correct, in my view, to try to resolve the debt problem in haste. What has taken 200 years to build (the debt mountain) cannot be taken down in a few years. Odysseus is correct: Stay the course and work on improving structure in the meantime.

Managing a large entity requires good numbers. True numbers are your friend. Celebrate the skills to ascertain true numbers; don’t shoot the messenger of bad tidings. It is easy for me to write down a smooth equation, but reality is spiced with turbulence and shocks.

Neither the government nor the citizens should be intimidated by temporary events, but instead look at the long run and discern underlying structure. Nature always regresses to the mean and working against the grain of nature is a losing proposition, as masterfully explained by Baruch Spinoza.

I hope that the idea of an intertemporal balance sheet will catch on. This is where the country can really see whether progress toward fundamental sustainability is under way. If so, confidence can gradually strengthen, and that would be a good thing.

Bob Traa is an independent economist. This is the 25th in a series of articles by him for Kathimerini titled “Notes for Discussion – Essays on the Greek Macroeconomy.”