Has the external competitiveness of Greece finally been fixed?

The previous Note for Discussion looked at a path for nominal gross domestic product and developments in the implicit GDP deflator; the latter being a broad measure of inflation in the Greek economy. We ended up asking ourselves, upon inspecting this “price vector” for Greece, whether external competitiveness has improved and has now been restored. If so, this would be confidence enhancing and a valuable objective achieved with the efforts made in the recession.

Competitiveness of a macroeconomy is a broad concept, and one indicator cannot do justice to monitoring all aspects of this concept. But there are some indicators that can be checked relatively frequently, they are relatively easy to compute, and they can give us entry ways into the world of competitiveness. One of these is productivity per person employed; another is looking at prices of goods and services; a third is whether Greek exports capture market share abroad; a fourth is monitoring the external balance of payments position over time to see if it is in balance or it tends to develop (semi-)permanent deficits or surpluses; and a fifth may be whether the country is able to attract foreign direct investment, among others.

In previous Notes for Discussion we have seen that productivity growth has been sluggish in Greece, which tends to complicate the management of competitiveness and macroeconomic balance. Thus, there is a good reason to try and improve productivity through efficiency-enhancing structural reforms. In this Note, we take a look at prices in their broadest reflection to see if this gives us any clues about Greek competitiveness and how it has evolved. We do this by comparing how inflation, as measured by the implicit GDP deflator, has moved over time vis-a-vis 19 countries that are using the euro as their currency (data from Eurostat). I will also present calculations for the Netherlands, for a bilateral country comparison.

We can assess two characteristics of the GDP deflator: its measure of the price level, and its rate of change over time – inflation. Both have complications and advantages. Comparing levels of prices is remarkably difficult, especially for a macroeconomy. We can compare the price of crude oil from one country to the next because oil is a relatively homogeneous commodity (and even this is not quite true, because crude oil comes in different forms, sulfur content, viscosity etc). A price level of a macroeconomy is nearly an incomprehensible concept, given the multitude of products and services it covers, and yet it exists and we can use it as one indicator of many.

When comparing price levels, we have to be careful when we measure such prices. If the economy is in a boom, prices may be somewhat elevated and that is not a “steady state.” If we measure during a recession, prices may be somewhat depressed, and that is not a steady state either. Thus, we need to find a time period or interval when the economy is humming along more or less close to its potential level of GDP and the output gap between where the economy is in cyclical terms and where it is in structural terms is small or nonexistent. Further, we need a period or interval when the balance of payments is more or less in balance without a huge current account surplus or deficit. Thus, we are looking to calibrate measurements for a period when the external equilibrium of the economy is deemed to be in decent shape, without large influences or imbalances that are not sustainable. We will call that period or year the “base year” from which we will track the development in the price index – the implicit deflator.

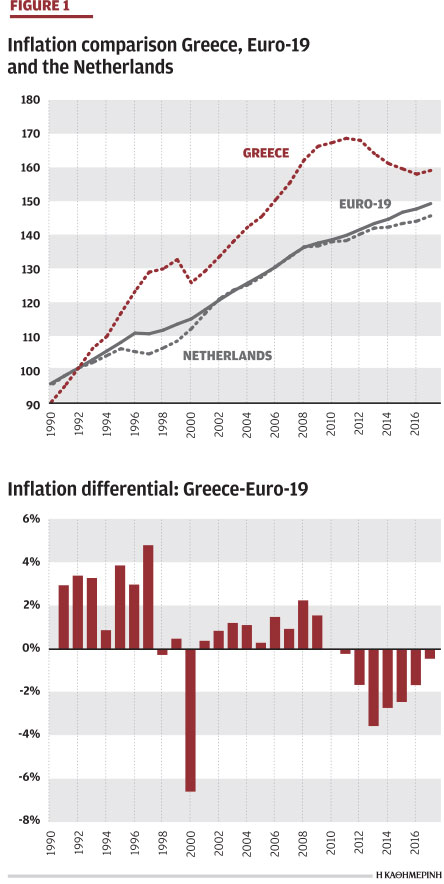

In the case of Greece, the last time period that the economy exhibited a relatively small output gap and a small external imbalance at the same time was around 1992-1994 (the output gap was around 0.5 percent of potential GDP and the current account deficit was around 1.25 percent of GDP – these are moderate numbers). As a result, I have taken 1992 as the base year for the calculations of the implicit GDP price index in euros (1992=100). By following the national accounts data year by year, we can calculate what happens to the implicit price index for Greece over time (as is shown in Figure 1 in the top panel).

To see how prices in Greece evolved relative to prices in partner countries, I have also calculated the same price index for the euro-19 group and for the Netherlands. Since Greece still had the drachma in the 1990s, I have adjusted the price index for Greece with the rate of annual depreciation of the drachma, and, indeed, there was a small devaluation in 2000 upon entry into the eurozone. A devaluation of the drachma means that Greek prices in euro equivalents decline, and thus that this improves Greece’s price competitiveness. Greece has no ability anymore to devalue its currency after adoption of the euro.

Figure 1 is telling. Greece came into the 1990s with inflation that was quite a bit higher than in the euro partner countries, and thus, the price level rose much faster than the euro-19 average (bottom panel). It is obvious that the devaluation in 2000 somewhat corrected the price level for Greece, but after entry into the euro, Greece continued to have higher inflation than its euro-area partners, and the price level sped up again above the equivalent of the eurozone. If we recall from previous Notes for Discussion that over this same time period, into the eurozone, the output gap for Greece ballooned and the external current account deficit also grew dramatically, then we conclude that all three indicators – price inflation, high positive output gap, and a deteriorating external position – became consistent with overheating of the economy and a loss in competitiveness. The waxen wings were withering.

To some extent, the Great Recession for Greece was an act of nature. When something is unsustainable, it is going to stop. And stop it did. The difference in the price level as measured by the price index of the deflator between Greece and the euro-19 partners maxed out at over 21 percent in 2010 when the economic adjustment began. In international comparison, a misalignment of domestic prices with trading partners that are using the same currency by over 21 percent is a grave overvaluation of the domestic price level. Whether we like it or not, recessions are cleansing acts of nature. They wring out the excesses in overvaluation and, in their wake, the economy’s growth potential and broad sense of “competitiveness” is determined by the ability to begin a new chapter with more comparable prices with trading partners.

For further comparison with Greece, the data from the Netherlands suggest that the latter succeeded at price and cost moderation in the 1990s, including to qualify for euro entry. This moderation of prices placed the economy in a good position upon entry into the eurozone, because its prices converged to the average from below, whereas Greece was not in a position to converge from above, despite a devaluation. Also, the Netherlands is highly dependent on foreign trade and it got hit by the financial crisis from the US, and the turmoil that resulted in the eurozone economies. Hence, to protect competitiveness, the Netherlands has further moderated its price and cost developments since the Great Recession and is now trending below the average of the euro-19. The economy is advancing between 2 and 3 percent growth, and it has a large current account surplus. Thus, while we should take such broad measurements only as indicative, they do inform the relative developments of countries quite well when taken over longer time periods.

When a deep recession hits the economy, as in Greece recently, the public can be understandably desperate, because they see jobs disappearing and income losses. They can be unfamiliar with economic statistics and it can generate a feeling of hopelessness and that there is no end to the downturn. This is what makes further inspection of Figure 1 interesting. If a recession is a cleansing device to place the economy on a more competitive footing again, then the price and cost corrections in the economy must come to an end at some point. But when is that point, or, to paraphrase a beautiful poem by Robert Frost, “How many more miles to go before we sleep?”

The figure shows that Greece is emerging from a seven-year period of competitiveness gains as Greek inflation, measured by the deflator, has been below the euro-19 average since 2011. Because of complications of nominal rigidities in modern economies, adjusting competitiveness is difficult and this is what causes the stress in society. In 2017, the gap between Greek prices and those of the euro-19 partners had shrunk to 6.75 percent (from over 21 percent at the peak). This is good progress. At the same time, the job is not finished, based on the numbers presented. The more moderate, but still higher prices in Greece can hold back the recovery in output, it still generates friction in competitiveness, and can lead to a re-emergence of current account deficits as the level of demand normalizes in the domestic economy.

The policy implications are clear: Greece should feel encouraged exiting from the most difficult period of the crisis in August 2018, but there is no room for high spending, new borrowing, or a letup in the need for structural reforms. Indeed, structural reforms are the most powerful, but slow-moving instruments to help ease further relative price gains in line with euro partners without causing new waves of unemployment (because the economy becomes more efficient and that helps net exports). Now that the economy is growing again, the speed of catching up with the eurozone price level is significantly slowing down. Some of this is to be expected, but it should not reverse into a new widening of the deflator path.

Bob Traa is an independent economist. This is the eighth in a series of articles by him for Kathimerini titled “Notes for Discussion – Essays on the Greek Macroeconomy.”