If the economy overheats, expect a downfall

The previous four Notes for Discussion focused on demographics, and how this constitutes the anchor for the size of the macroeconomy. Within the overall envelope of demographic development, countries can temporarily grow faster than warranted by population growth to the extent that a reservoir of unemployment exists from which to draw additional labor resources, until unemployment is reduced to a “natural” level; and then the economy’s growth potential is back to demographic developments.

The previous Notes also stressed that demographics determines the size of the economy, but not the standard of living. The latter depends not on the size of the economy but on efficiency, as promoted by a continuous search to use resources better through structural reform. This, we captured by looking at the evolution of labor productivity over time – how many goods and services can one unit of labor produce over time? In the long run, this is what really matters.

In this Note, we bring the concepts of demographics and productivity together by looking directly at the dynamics of real GDP in Greece over a long period of time – 110 years to be precise. I have researched real GDP growth data from 1970 onward, and combining the latest demographic projections with an aspirational assumption that Greece should aim to improve labor productivity growth to 1.5 percent a year, we can construct a narrative of what could happen to real GDP in the future through 2080. Since this is the future, I offer no guarantees.

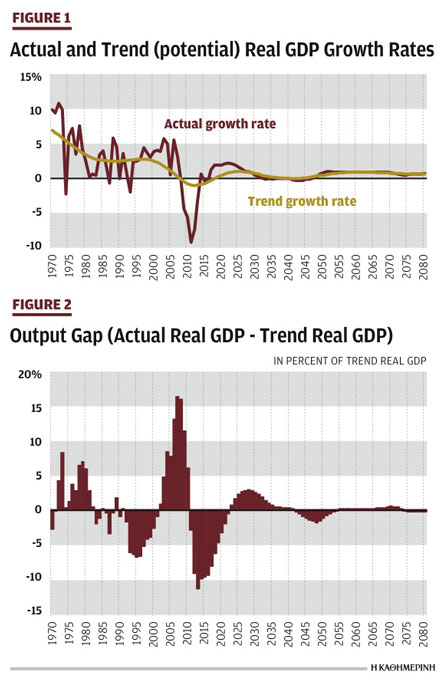

Figure 1 shows the growth rate of real GDP in Greece from 1970 until 2080 (baseline scenario). The data in this picture through 2017 are as reported; those from 2018 onward are obtained by assuming that the current high unemployment rate is gradually reduced to 7.5 percent in the 2020s, upon which the demographic anchor of population growth and its derived employment growth potential again take over. We combine this potential growth in employment with a gradual improvement in the next 5-10 years of labor productivity growth from the current low level, close to zero, to 1.5 percent a year. Real GDP growth in the projections for the long run then becomes the growth in employment combined with the assumption that each worker, on average, improves productivity by 1.5 percent a year.

The figure shows that year-to-year growth can be quite volatile. In the projections this volatility is not present because we assume a gradually evolving economy. In reality, the future will also show annual ups and downs. One important task of policy making is to reduce this volatility to a minimum and manage the economy in a countercyclical way. Volatility is uncertainty and that reduces well-being, as the experience in the sharply negative growth rates of the 2010s has shown. Because the historical path is so volatile, we like to get a view of the smoothed averages of the past, all the way extended to the future projections. This is our underlying scenario given the assumptions we have used. This smoothed path for the growth rate in real GDP over the long run is shown in the gradual line that averages through the volatility of the historical record. We interpret this line as representing the underlying potential or trend real GDP growth line of the Greek economy.

Coming out of the Second World War, trend growth in Greece was between 5 and 10 percent. There was lots of construction for the rebuilding of the country and the rebound from the disaster allowed the economy to jump in size. Also, population growth (baby boomers) and employment growth were much higher than today, so both the actual and the trend growth line show this strength coming into the 1970s. Then, as rebuilding had advanced, and population growth started to moderate, the actual and trend growth rates settled down to about 2.5 percent in the 1980s and 1990s. Greece entered the eurozone in 2000 and there was a big credit boom as financial deregulation took place and the (currency) risk premium was lowered: The actual growth rate in the 2000s improved to around 4 percent a year on average, but the potential growth rate started declining as risks were building up in the economy from the debt-fueled boom.

We can see in the picture that growth exceeded trend in the 2000s and that it fell well below trend in the 2010s. Following a moderate second dip in 2015, we are now at the 2018 point where the economy, based on all the assumptions we have described, is poised to grow a few years above long-run trend, as the mass of the unemployed returns to work. This provides hope for the 2020s, if carefully managed, that the economy can find some dynamics again – in these projections the growth rate may hover around 2 percent for a while, driven by a return to employment and gradually recovering productivity growth. As anticipated, these rebound effects should be completed before the 2030s and (slow) demographics takes over again. The 2030s and 2040s could well hold very weak headline growth, simply because the population and employment are declining, as per the recent demographic long-run projections. By the 2050s we are in a new generation where population growth slightly recovers and combined with 1.5 percent productivity growth, the economy may advance at around 1 percent a year.

We can think of the 2000s as the “long hot summer of growth” for the Greek economy, with a boost from the euro, the Olympics, and good sentiment as Greece won the European Soccer Cup for country teams. Underneath the surface, however, population slowdown continued and clouds were gathering from the fact that this long hot summer was financed with debt, not equity. This summer ended in a “perfect storm” from 2009 onward. Greece had set itself up for this storm by accumulating too much tinder brush of debt. What caused the perfect storm was the overshooting of the economy, it overheated as net spending was too elevated, and lost competitiveness, poor procyclical instead of countercyclical fiscal policies, and then all was lit by the spark from the US financial crash that stopped the financing carousel. Daedalus’ foreboding went unheeded.

We can briefly return to evidence of labor productivity growth with these even longer time series. Labor productivity growth from 1980-2010 is exactly 1.5 percent a year. The long-run average from 1980-2017 shows labor productivity growth of 1.1 percent a year. In the projections above, we impute that labor productivity growth returns to 1.5 percent a year in the 2020s, and as a result, for the whole period 1980-2080 that would yield an average of 1.3 percent a year. Thus, we are not making pessimistic assumptions about the future on productivity recovery. Indeed, if Greece is to converge with other euro countries in the future, then structural reforms are essential to make the economy more efficient. Only through this process will convergence be a sustainable process without a return to debt accumulation. Since debt actually needs to be controlled over this long future, it is possible that this will restrain the recovery in aggregate demand and also impair productivity growth below what is assumed in the calculations above.

Finally, we can look at real GDP developments in a different context. Derived from the same data as used above, Figure 2 shows the evolution of the “output gap.” The output gap does not focus on annual growth rates, but rather on the level of real GDP in relation to its trend. Thus, we can ask the question: At any point in time, how does actual real GDP compare with a notion of “potential real GDP” – what is the gap between these two? If actual real GDP is above potential, then the economy can overheat and inflation and wages can rise to damage competitiveness. If the economy goes through a deep recession, then actual real GDP will be below potential and wages and prices are bound to ease off. Thus, the output gap is a crucial indicator for countercyclical policy – if the economy is overheating (activity is very strong), the government should run a surplus and pay down debt. If the economy is cooling down too much, then the government could add some fiscal expansion to level off the consequences for employment and growth – provided that the additional impulse can be financed at reasonable costs.

In the current conjuncture, the last observation is crucial, because Greece is starting off with too much debt and thus should not place more net debt. This (asymmetrically) limits the ability to run countercyclical fiscal policies, if growth cools off. It also puts, therefore, a huge premium on the need for structural reform, so that the economy becomes more flexible and can generate growth on its own, as with a better-lubricated and better-calibrated engine, without the need for government stimulus and the minister of finance pushing hard on the accelerator.

This output gap figure is quite interesting. It shows that cycles last for about a decade or longer. The 1970s were slightly hot as actual real GDP was running above its potential or trend level; the 1980s were relatively quiet. Then came a short recession in the early 1990s and economic growth was held back as Greece made efforts to qualify for euro accession – the economy was held back somewhat from its potential level for the decade. This changed in the early 2000s as the “summer of growth” came and with lots of easy and cheap credit, the economy powered well above longer-run potential. This is the picture of overheating that set Greece up for a sharp loss of competitiveness, big debt buildup, and the cold shower of the perfect storm of the 2010s when the output gap became sharply negative again – the economy first overshot on the upside and then fell on the downside.

The data suggest that the economy is now starting to recover and the negative output gap is shrinking, but it will not be until the 2020s, with the assumptions that we have made, for the economy to feel strong again and a serious reduction in unemployment may be expected. This “upswing” above potential is projected to last into the 2030s when the economy is to gravitate to its long-run potential. This is by design given the way the model has been set up; we cannot simulate an economy, or tell an economic narrative, for large departures from potential in the future, so the calculations naturally drift to displaying the sense of close-to-potential in the long run and the output gap is insignificant in the long-run projections when the cycle is coming to rest. The reality, however, will be that volatility will continue much bigger than shown here, and the art of good policy making is to know what to do then, and not to overreact to temporary setbacks.

Closing thoughts

– The data tell an entirely plausible narrative of the evolution of the Greek economy. Volatility is (too) high and the important cycles last for about a decade. An effort should be made to improve countercyclical policy.

– The seeds of the big recession were sown in the overheating of the economy in the 2000s, after accession to the eurozone when credit became plentiful. When borrowing becomes cheap, that does not mean that a country should leverage up.

– These data and assumptions suggest that average potential growth in real GDP for the period 2018-2080 is 0.6 percent a year. Actual growth in the next few years may be higher, around 2 percent into the 2020s, given the task of absorbing the pool of excess unemployment.

– Since debt is high, structural reforms are of utmost importance to get productivity up. This is the true source of future increases in well-being of the population. Greece has no independent monetary policy by virtue of the eurozone, and fiscal policy must be contained given the need to pay down debt. Errors of the past should be avoided.

– Different analysts may have different assumptions. Assumptions matter because over such a long time period, small changes can lead to notably different outcomes. The government is well taken to do careful independent research on potential growth and what this means for structural and fiscal policy. Whatever path the governments of Greece choose, these need to be carefully explained to the public so that the political choices that Greece makes are well grounded in the true preferences of the population.

Bob Traa is an independent economist. This is the fifth in a series of articles by him for Kathimerini titled “Notes for Discussion – Essays on the Greek Macroeconomy.”