Greek agriculture and the EU – inconvenient truths

The deepest harm inflicted on Greece by the European Union, among the many benefits, is probably that it has maintained a large agricultural sector. Hundreds of thousands of young Greeks, instead of working hard in creative ways to attain a better future, just sit around waiting for European subsidies to materialize. Instead of utilizing their skills to create useful knowledge and innovation, they devote themselves to devising ways to fool the EU and block Greek roads.

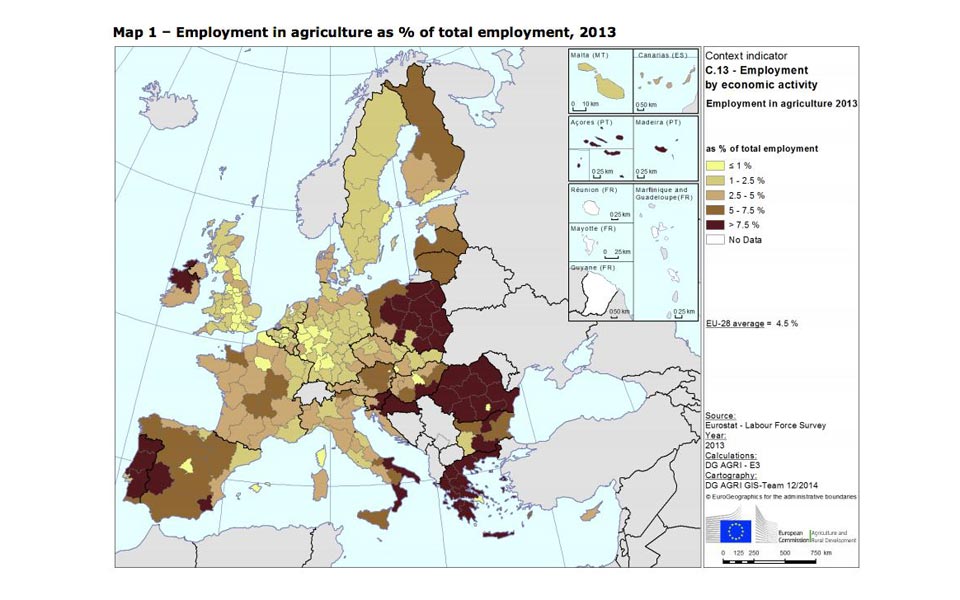

Notwithstanding what most Greeks think, the country is not truly agricultural – only about 13 percent of the population works in the sector. However, thanks to the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the Greek farming sector remains unusually big by European standards. Greece has the most farmers per capita after Romania, definitely more than the number that is needed or what the market would sustain.

The biggest issue with the farmers is not that they regularly disrupt traffic and commerce on Greek roads, nor that they regularly support the most conservative currents in Greek politics. Farming in Greece simply does not contribute to the common good: Farmers hardly pay any taxes (to finance the roads they are blockading, for example), nor do they properly contribute to social security. And they do not contribute because they have no surplus of resources to share. This lack of resources is not manmade, it is simply to do with the lack of arable land: Farming on a large scale is doomed in Greece, it's as clear as that.

Conventional wisdom within Greece and decades of development policy consider farming to be very useful. Many voices in the public debate argue that a return to farming might even be a solution to the Greek crisis. Both ideas are fundamentally wrong: Greece is not fit for large modern farms and farming cannot substantially contribute to GDP in a modern economy.

Consider the US as a modern economy, which incidentally also has the most productive farming sector. In the aggregate US economy farming only contributes about 1 percent and no state (except for the Dakotas) has a farming contribution higher than 5 percent. In Greece, farming contributes about 3 percent of GDP, approximately four times less than its share of employment, meaning that farmers are about 75 percent less productive than the average worker.

Greek farming is so weak because farming, just like any modern productive activity, requires economies of scale. Modern farms in Ohio or Florida use GPS guided driverless tractors, advanced irrigation systems with humidity sensors etc. Today’s farmers are managers of big organizations, far from the suntanned sweating stereotype we read about in novels. Farming in Greece is so backward, not because of any lack of human capital or access to the tractor market, but because of a lack of scale. The average farm in Greece is 7 hectares, versus 26 ha in the Netherlands and almost 81 ha in Florida. Greek farmers are just too numerous compared to the efficiently farmable part of the land (which is way too small anyway because of geographical factors). Expecting world-class farming in Greece is like expecting someone to build a BMW with a screwdriver and duct tape.

As a result, world agricultural prices, which are formed in the American Midwest and the Argentinean Pampas, are lower than the cost of Greek producers. The only factor keeping Greek farming in existence is EU support in the form of duties on foreign food and large subsidies provided to European producers. For decades, one in every two euros spent by the EU was not invested in education or research, or even consumed by welfare, but went to subsidize mountains of butter and rivers of wine.

What should we do now? Leave the farmers without gainful employment? Run out of food? Let the Greek countryside rot? Not quite.

First, there might not be much to be done for older farmers, but there is no reason to encourage new generations of them by distorting incentives. Why not give every young person considering farming a choice? Run a farm or study at any university of your choice on the planet; fuel subsidies for tractors or funds for a start-up. Give them the freedom to choose; they’re not irrational, just victims of an irrational choice set inflicted on them.

To the extent that the EU is unable to fundamentally reform the CAP, given Greece's economic situation, it could still try to ask for a shift in the CAP funds it is currently receiving, toward more productive aims, as listed above. Although it might be legally tricky, the EU and IMF would find it very hard to argue against such a move.

Now, what are we going to eat if young people stop farming? What every non-farming city dweller eats: Ohio corn, Ecuador bananas – whatever they want, cheaply and in unlimited quantities. The idea of agricultural autarky is not just economically silly but plainly infeasible for most of the densely populated world.

And what about the natural landscape? Won’t it be degraded if farmers are not there to maintain it? On the contrary, farming is a particularly harmful activity. Where farms are now, there used to be forests. Where millions of tons of water are used for irrigation purposes now, there used to be creeks and rivers. If we abandon the land that is of negative economic value for farming (removing the subsidies), we will have space for forests, parks, even urban expansion. In Greece’s case, there will be more space for tourist development too, which, per unit of income, is much more eco-friendly than farming.

Let’s be clear: No modern country got rich because of agriculture, not even countries with a long tradition of culinary marketing, such as France. Greek agriculture can and will advance by focusing on small high-quality niches. But the Greek economy (or more specifically employment levels) will not advance based on farming. Let this ancient activity run its course into civilized retirement, a marginal sector for a few good men (and women) producing things they love. And let everyone else move on at last.

P.S. Many thanks to Saqib Jafarey for comments and suggestions.

Sotiris Georganas is a Reader (Associate Professor) in Economics at City University London.