Catalan elections: The secessionists’ wrong ethnic message

On September 27, citizens of the Spanish autonomous region of Catalonia were called to vote for the composition of the new regional parliament.

Incumbent Regional President Artur Mas, a center-right Catalan nationalist who recently converted to secessionism, fought the elections in alliance with the traditionally secessionist leftists of Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya. They did so on a one-issue platform, namely secession from Spain within the first 18 months following their election.

With not quite 40 percent of the popular vote, their secessionist “Jointly for Yes” coalition fared worse than expected. Whatever remaining hopes they have of leading the new government hinge on the support of the far-left “anti-sistema” party Candidatura d’Unitat Popular (CUP), whose 10 members of parliament are thus pivotal.

Everyone from local newspaper La Vanguardia to the Financial Times agrees that the interpretation of the results is not straightforward. On the one hand, thanks to an electoral system tilted in their favor, secessionist forces did win an absolute majority of seats (72 out of 135 seats). On the other hand, despite fighting the elections under ideal circumstances, the secessionists fell short of their proclaimed goal of winning an absolute majority of votes. Given their radical, anti-institutional and pro-democracy rhetoric, that fact is now crippling them.

So the question is, why did the secessionists fail? Why did they fail to convince a majority of Catalans about the benefits of secession at a time when (a) state schools and public media in Catalonia have been controlled by nationalists for over three decades, (b) immigrants from the rest of Spain have been here long enough to virtually not even remember their roots, (c) Spain’s economic system produces record-high unemployment and cronyism, and (d) the central Spanish government is in the hands of the notoriously conservative and clumsy Partido Popular (PP)?

The answer, I believe, must be sought in the ethnic composition of the vote. Put simply, not enough non-ethnic Catalans voted for secessionist parties. That, in turn, occurred because the Catalan secessionists sent the wrong ethnic message. By relying on increasingly anti-Spanish rhetoric (a strategy which may have been necessary to mobilize their core voters), they scared off those segments of the population who still feel Spanish, partly Spanish, or merely not purely Catalan enough.

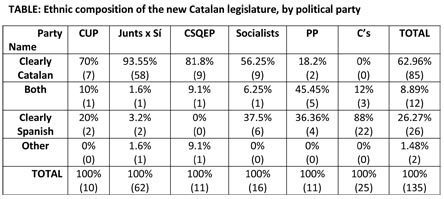

To get an idea of how this occurred, observe the cross tabulation below. The columns are defined by political parties, arranged from the most secessionist (CUP, which proposes to integrate into an independent Catalan republic territories where there is no popular demand to do so) to the most unionist (PP and Ciutadans, both of which have only reluctantly and belatedly admitted to the pressing need to accommodate Catalan demands in the Spanish Constitution). The rows are defined by the composition of the names of newly elected MPs, ranked from most Catalan (Catalan name, at least one Catalan surname, and a traditionally Catalan “i” linking the two surnames) to most Spanish (Spanish name, at least one Spanish surname, and no “i” linking the two surnames), with an extra category for “other.”

Source: Author’s own calculations based on data from the Catalan Corporation of Audiovisual Media (CCMA).

Clearly, all parties in favor of the “right to decide” have a majority of ethnically Catalan MPs, and vice versa. That cleavage becomes even clearer when comparing the party explicitly created to promote secession (Junts x Sí) with the party explicitly created to fight against it (C’s).

With so many of its electable candidates sharing the same purely Catalan origin, Junts x Sí had to send a signal to the effect that it was not an ethnically motivated movement which, once in power, might seek to implement sectarian policies. It chose to do so by signing up three non-ethnic Catalan candidates, including a sociologist of Moroccan origin and the president of an association created to convince Spanish-origin voters to back secession.

Yet that strategy backfired, and it did so for a very simple reason: It was not a strategy that could credibly distinguish an ethnically motivated party trying to hide its true nature from a civically motivated party seeking to create a more prosperous and inclusive nation. Put differently, including those three candidates was plainly too easy – almost costless – and therefore at best meaningless.

Far from unambiguously signaling that the process of secession is backed by non-Spaniards, it was seen as too reminiscent of the French Front National’s sporadic and grotesque signings of African-origin candidates, such as Sofiane Ghoubali or Mungo Shematsi, or former French president Nicolas Sarkozy’s promotion of Rachida Dati. Spanish-origin voters could just read through Junts x Si’s strategy all too easily – or at least so they thought.

The deeper significance of it all is that, even in its most civilized and least violent version – as in Catalonia – nationalism remains a largely divisive ideology. Thereby may lie its strength, of course, but also its weakness. As long as the demographics do not change, the “vast social majority,” which President Mas had been hoping for, will just not exist. That should be enough for the European Union to not lend its support to the Catalan nationalist dream.

Yannis Karagiannis is Associate Professor at the Institut Barcelona d’ Estudis Internacionals (IBEI).