Unearthed documents about the first act of the Greek Civil War

The expectations of the Communist Party of Greece (ΚΚΕ), according to confessions and correspondence seized by the British

“History is never a closed book or a final verdict. It is forever in the making… The great strength of history in a free society is its capacity for self-correction.” (Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr, “Folly’s Antidote,” editorial in The New York Times, January 1, 2007)

In commemorating the anniversary of the Battle for Athens from December 1944 to January 1945 – commonly known as the Dekemvriana – interested readers have at their disposal a substantial body of publications by various authors who examine virtually all aspects of the conflict at its national and international levels. Although the sequence of events is no longer in dispute, conflicting arguments remain regarding the roots of the crisis and the specific goals of the two camps, especially of the Left. What is reasonably certain is that by the time of the country’s liberation from German occupation, the national “dichasmos” (schism) between republicans and royalists had morphed into a virulent clash between a Marxist Left and an assortment of anti-Left factions ranging from liberals to monarchists, each camp determined to prevent the other from seizing power.

The feuding had been inflamed by the hardships of the enemy occupation and the hostility between the armed Resistance movement which British officials had initially fostered but failed to harness to the Allied cause. In January 1943 decisive Soviet victories at Stalingrad had a subtle but significant impact on the Greek political dynamics. The leadership of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) became convinced that its popularity among the masses, whether genuine or imposed through fear, the strength of the National Liberation Front (EAM, civilian) and the Greek People’s Liberation Army (ELAS, military), and, above all, Soviet support would enable the Communists to come to power. There was even hope that despite festering territorial and ethnic disputes which poisoned interstate relations in the Balkans, ideological affinity would induce the fraternal parties of Yugoslavia (Tito) and Bulgaria (Dimitrov) to help their Greek comrades succeed in dominating Greece.

Feeble attempts to reconcile the two camps through compromise failed. In August 1943, at a British-sponsored conference in Cairo of politicians and Resistance leaders, bitter dispute over the establishment of a coalition government and the symbolically critical issue of the monarchy’s future destroyed all possibility of compromise. The formation of a Leftist “Provisional Government” in areas under EAM/ELAS control was soon announced, followed by renewed ELAS attacks on its principal rivals in the Resistance.

Fear of the communists’ growing strength in still-occupied Greece drove the British authorities to take practical measures to defend Athens against a communist coup after liberation. In September 1944, at a meeting in Caserta, the principal armies of the Greek Resistance – ELAS and the National Republican Greek League (EDES) – agreed to be placed under the command of a British lieutenant general, Ronald Scobie, and ELAS was ordered to keep its main forces away from the capital. (Its weaker rival, EDES, had been confined to remote Epirus.) The Greek infantry units Third Greek Mountain Brigade (Rimini) and the Sacred Squadron (Ieros Lochos), were hastily brought to Athens from abroad. There were also secret negotiations to incorporate in the defense of the city select units of the collaborationist and highly unpopular Security Battalions.

In late November, with Prime Minister Georgios Papandreou’s approval, Scobie demanded the disarming of ELAS by December 10, and the creation of a new national army. Scobie’s order precipitated the resignation from the cabinet of the Leftist ministers and the collapse of Papandreou’s coalition government. The political crisis was followed by widespread strikes and mass demonstrations organized by the Left. On Sunday, December 3, the indiscriminate shooting by police on a large demonstration of unarmed protesters in Syntagma Square sparked the “Battle for Athens.” In retrospect, despite sporadic violence and fears of coups, there had been no evidence that either side had been planning an armed attack on the other. ELAS’ combat-tested units remained in Macedonia, while major ELAS units were spread across central Greece. The veteran communist and brutal chief (“Kapetanios”) Aris Velouchiotis was sternly reprimanded by the party leadership when he proposed that ELAS advance on Athens.

But after the bloody incident of December 3, which a British infantry platoon and few policemen quickly brought under control, isolated EAM/ELAS attacks on police stations and the Naval Cadet School in Piraeus began spreading across the capital and gradually engulfed much of the city and its suburbs in five weeks of bitter street fighting. The defeat of the insurgents was largely brought about by the arrival of substantial and heavily armed British troops rushed in from the Italian front. On December 25, as the fighting continued, Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Foreign Minister Anthony Eden arrived unexpectedly in Athens. At a hastily convened meeting with bewildered Leftist leaders and in the presence of Archbishop Damaskinos and representatives of Britain, the United States and the Soviet Union, Churchill castigated the Leftists for damaging their country’s national interests and disrupting the Allies’ war effort. Speaking to journalists, Churchill threatened to have Greece placed under international supervision. Although the fighting briefly resumed, ELAS was soon defeated and retreated from the capital to the countryside. A truce was concluded on January 11 and a peace agreement was signed at Varkiza on February 12, followed by the disarming of ELAS.

The sudden eruption of heavy fighting in the capital and the eventual defeat of the insurgents raises questions that, decades later, deserve authoritative answers. What were the motives and goals of the KKE leaders regarding a violent situation they had helped precipitate? How did they justify to themselves and their followers their resort to military action in the densely populated capital against domestic and foreign adversaries? How prepared were they to confront with any hope of success their multiple opponents in a crisis which in a matter of days had escalated from angry political feuding and mass demonstrations to fierce urban warfare? Were they induced to overthrow the British-backed regime by encouragement and expectations of assistance from the Yugoslav and Bulgarian comrades and, ultimately, from Stalin? If so, what had they been promised by their communist neighbors and by Moscow? What concessions were they prepared to make to their ideological allies in return for their assistance?

The purpose of this article is not to offer a balanced overview of the causes and course of the Battle for Athens. Rather, it is to address the questions raised above by presenting recently declassified British and American intelligence reports which include historically important communications between KKE and ELAS leaders and with their foreign allies as transmitted to their superiors by foreign observers in the field. Statements by Western officials are included only when they present important dimensions of the conflict as an international issue. By focusing on the communist camp this narrative is therefore one-sided and must be viewed as presenting fragments of only one key portion of the Dekemvriana drama. As much as possible, it attempts to narrate history in the protagonists’ own words.

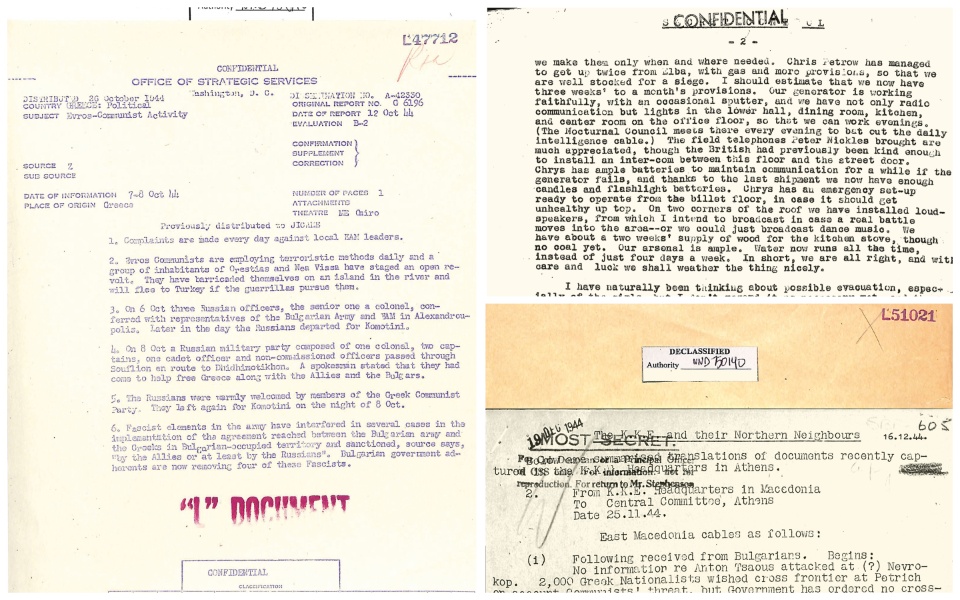

American officials were often critical of Britain’s handling of developments in wartime Greece – especially during the Dekemvriana crisis – and sought to collect independent information through their Office of Strategic Services (OSS). At the same time, they acknowledged that for historical and practical reasons the British were better informed about Greek affairs and Americans in the field often relied on their British counterparts for what they reported to Cairo and Washington. OSS documents identified in this article as “captured KKE documents” were seized by British officials during raids on KKE offices in Athens and elsewhere in early December and were shared in translation with the Americans. They are deposited in the American and British national archives (NARA diplomatic file 868.00 MacVeagh dispatch 427, January 22, 1945, RG 226, OSS L Series, and WO 204/8903, 1944, Security Intelligence. M.E.). The Greek originals have not been located and were probably destroyed.

For most of the war years Soviet policy toward Greece remained consistent: It advocated that the KKE should seek accommodation with the Greek government. A Soviet military mission under Colonel Gregori Popov, which arrived in ELAS-held territory on July 26, 1944, had advised the KKE to agree to “any” British demands. Specifically, it urged the communists to enter Papandreou’s “Government of National Unity” created by the British-sponsored Lebanon conference (May 17-20, 1944). On August 17 EAM announced its decision to join the coalition. On September 9, 1944, (Document 1) the OSS reported that the “Russian Mission to Greece told EAM to agree to any demands of the National Government. Levkos (pseudonym?), member of EAM Central Committee, told [the] meeting of representatives that at the moment the Russians are weak and poor, therefore, EAM must accede to Britain’s demands through the National Government. He also said that representatives should spread a rumor that Britain has promised to Bulgaria the territories of Thrace and Macedonia, and to Turkey the islands of the Dodecanese, Samos, Chios and Mytilene. Meanwhile EAM’s policy should no longer be political but military in order to gain the full support of the people. This changeover, he said, should be effected before the National Government arrives in Greece, otherwise the people will not listen to EAM.”

During the period from the German withdrawal and the arrival of the government-in-exile, the KKE/EAM leadership was confronted not only with the question of participation in the Greek government, but with the issue of supporting an autonomous Macedonia. While the Nazis occupied Greece, in Thrace and Eastern Macedonia, the Bulgarians were both an occupying and a colonizing power. A Soviet report dated September 17-18 (Document 2) noted that a British military mission had arrived from Drama in Sofia and contacted officers on the staff of Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin, the Soviet general who led Soviet troops in the Balkans. The Soviet and British officers “discussed the request for withdrawal of Bulgarian troops from Aegean Thrace and Macedonia.” Stalin instructed Tolbukhin a few days later “to avoid any political discussion with British and US representatives – the talks will be held directly in Moscow.”

In early October a Russian military delegation toured Bulgarian-occupied Thrace, visiting Alexandroupoli, Soufli, Komotini and Didymoteicho. According to an OSS report (Document 3), the Soviet delegation, led by a colonel, “conferred with representatives of the Bulgarian Army and EAM… [and] stated that they had come to help free Greece along with the Allies and the Bulgars. The Russians were warmly welcomed by members of the Greek Communist Party.”

On October 9, 1944, meeting with Stalin in Moscow, Churchill suggested to his Soviet host, “Let us settle about our affairs in the Balkans,” and scribbled on a piece of paper what became known as the percentages or spheres of influence agreement. Listing a division of responsibility for Britain and the Soviet Union over five East European states, it proposed 90% for Russia over Romania and 90% for Britain over Greece. According to Churchill’s account, after a slight pause, Stalin made a large tick mark with his blue pencil and passed it back. (Churchill, “Triumph and Tragedy,” 227)

In early November the KKE sent a communication to Georgi Dimitrov, the Moscow-based Bulgarian communist leader, discussing a possible autonomous Macedonian state. The KKE reported (Dcocument 4) that since Bulgaria was willing to cede the Petrich area to an independent Macedonia, the Greek Communist Party saw no reason why the Greek districts of Kastoria and Florina should not be ceded to Macedonia by Greece. The communication went on to say, however, that the Greek Communists were firmly of the opinion that no part of the Serres, Drama or Kavala areas should be ceded to Macedonia, but should remain as part of Greece. Throughout the conversation it was taken as understood that the new Macedonia would form part of the Yugoslav Federation.

“Our policy lacks direction, and if we had paid more attention to this we could have increased our influence over the masses,” the KKE Central Committee warned in a directive to the EAM Central Committee on October 23 (Document 5). The KKE outlined five steps EAM should take to rectify the situation:

“1. The CC of EAM must visit the British ambassador and accompany him to our quarters where we must prepare a good reception which will be given publicity in our press. 2. Col. Popov must visit the HQ of the 1st Army Corps of ELAS, which will be written up in our press. 3. We should ask Moscow to arrange regular and more interesting Greek broadcasts. The present programs are very poor. The French transmissions from Moscow are excellent. 4. We have influence over many political figures, and we have many members who are lawyers, bank employees, civil servants etc. Thus there is no reason why we should not place some of them in official or semi-official government posts, in order to control the administration, which today is in the hands of the Fascists… 5. Why did our newspapers not comment on the telegram sent by Papandreou to Stalin thanking him for his help in the liberation of Macedonia? This was a case in which we could have gained a real political victory.”

The KKE vacillated between maintaining good relations with the Yugoslav Partisans, which required concessions on Macedonian autonomy, and political support for EAM-ELAS in Greek Macedonia. In a telegram from Leonidas Stringos, the KKE leader in Macedonia, to Ioannis Ioannidis at KKE Headquarters on November 4, Stringos (Document 6) reported that a battalion of 300 Slav-speaking troops of Gotse had crossed into Greece north of Florina, with another battalion at the border: “They tried to take Florina but after an engagement of 2 hours withdrew to Haghia Paraskevi…[Yugoslav Partisan leader] Tempo made following declaration to our [KKE] representative: ‘I am very much afraid that the KKE together with the British will find themselves up against New Yugoslavia and Soviet Union. Detachments which arrived will be armed by us and sent south; if ELAS tried to prevent this they will defend themselves. If you attack them we will send assistance.’ In Serbian Macedonia people shouted at our representative: ‘Death to them! Hang them!’ The disarmed and denuded Slav-Macedonians who had deserted to us. Telegraph whether you approve of our attitude. Situation always critical. Disturbance of our relations with Yugoslavia will damage our cause.”

In Athens, the political leadership of the KKE had agreed to demobilize ELAS, but only if the Greek government’s Rimini Brigade and Ieros Lochos forces were also demobilized before a national army could be created. When Papandreou temporized, in a telegram on November 9 (Document 7), the KKE leadership in Athens warned the EAM leadership in Thessaly and Sterea Hellas (Central Greece) of a possible rightist coup:

“Reaction aims to create conditions favorable to a coup and dictatorship. Watch. ELAS should remain at their position until prerequisites for a normal development of the situation are secured. Will disband only when the forces from Egypt are disarmed and a new army is formed under the command of men enjoying the confidence of the fighting people. Politophylaki [EAM police force] should remain in charge until ethnophylaki [government police force] corresponding to the people’s will is formed. Gendarmerie should be dissolved. See that a democratic front is created against the danger of monarchy.”

The KKE did not seek to further polarize the situation. On November 20, 11 days after his warning to his forces to be on alert, KKE General Secretary Georgios Siantos (“O Geros” / The Old Man) instructed General Stefanos Sarafis, head of EAM, to meet with General Scobie. Siantos also scolded Aris Velouchiotis for creating provocations (Document 8) and told him that he “should not sign correspondence to General Scobie. Kapetanios’ conference and your suggestions to them [to descend on Athens] unwise. This at the present moment creates confusion and very risky misunderstandings. We draw your attention to such matters. Markos should go to his post [in Macedonia].”

In another sign that the KKE was still seeking to keep its options open, two days later (Document 9) Siantos called on party members, ELAS members, and members of the EAM’s National Civil Guard to be the first to join the National Guard being created by the government.

“Communists and EAMites must organize themselves securely within the National Guard. Members of this body should be perfectly free to read any newspaper and discuss politics. This need not interfere with carrying out their duties in a model way. Members of ELAS and National Civil Guard of 1936 class must hand in their weapons to ELAS before they join the National Guard. Remaining members of National Civil Guard, after handing over duties to the National Guard, must join ELAS with all their weapons and equipment. We will keep you informed of any change in the situation.”

On November 25 (Document 10), Stergios Anastasiadis, the KKE leader in Macedonia, relayed to the KKE Central Committee in Athens other concerns from the north: “Following received from Bulgarians. Begins: (1) No information re Anton Tsaous attacked at (?) Nevrokop. 2,000 Greek Nationalists wished to cross frontier at Petrichon on account of Communists’ threat, but [Bulgarian] Government has ordered no crossing of frontier by Nationalists. Inform us of campaign against Nationalists so that we can give all possible assistance. Kostoff (Ends)”

The greater the number of victims, the greater the hatred for the British

In late November, the KKE’s political fortunes in Athens appeared to worsen. Prime Minister Papandreou had rejected the Communists’ consent to demobilize ELAS only if the Mountain Brigade and Ieros Lochos were also demobilized. Alarmed, Siantos telegraphed KKE offices throughout Greece on November 28 (Document 11):

“This is unacceptable. Situation critical. Watch and be ready to repulse any danger. British and Greek opposition demand disbandment of People’s Army by December 10. At the same time they insist on retaining Greek armed bodies organized by Greek fascists in the Middle East with the argument that they constitute an Allied force. They intend to impose a fascist dictatorship with the aid of the above fascist bodies and secret armed forces of fascists in Athens after ELAS has been disbanded. Trusting our organized popular forces, a large portion of which are armed, we have made it a condition for the disbandment of ELAS that all armed forces of the opposition, including the Gendarmerie, should be disbanded simultaneously. The British have refused this and are pressing opposition to start civil war. Which may start any time. We are ready to take up the challenge.”

The following day Siantos again (Document 12) wired KKE/EAM bases in Macedonia, Epirus, Thessaly, Central Greece and the Peloponnese that the situation is “extremely critical. Opposition is ready to start civil war by insisting on retention of Mountain Brigade and Sacred Company, and on disbandment of ELAS. Enlighten [the] public. Take all measures to face any eventuality. Justice is on our side. Have faith in our policy and our forces. Victory is ours.”

By the next day, November 30, the KKE had prepared for military action. Major General Manolis Mandakas, the ELAS military commander in Athens, wired ELAS Headquarters (Document 13) for ELAS to send “explosives and mines for probable fighting in built-up areas, preferably through 2nd Division. It is likewise considered advisable that six demolition squads should go to 1st Army Corps. Their men should be sent in small groups (‘sporadically’) under the guise of [going on] leave, in the shortest possible time. The dispatch of W/T sets requested, together with suitable personnel should also be expedited.”

The same day Siantos advised ELAS HQ (Document 14) that General Scobie’s order to demobilize ELAS should be ignored:

“Scobie has printed an order and proclamation concerning demobilization of ELAS on December 10. No similar government order has been signed by Council of Ministers. This is dependent on political agreement which has not as yet been reached. Until the situation is cleared up no demobilization of ELAS should take place. On the contrary, you must be ready to repel any attack which may eventuate. We will keep you informed of developments in the situation. Under present conditions it is impossible for National Civil Guard to hand over its duties to the newly formed National Guard.”

In late November the KKE had sent Andreas Tzimas and Stergios Anastasiadis to confer with Tito and Bulgarian leaders. Four days before the shootings in Syntagma Square, on November 30, Anastasiadis reported to KKE leaders in Athens (Document 15) in a second message from KKE/EAM HQ in Macedonia that he “saw Bulgarians and Tito. They advise we must insist on not being disarmed. No British interference.”

From that point conditions deteriorated rapidly. On Friday, December 1, the three EAM ministers in the Papandreou government resigned, and on Sunday, December 3, EAM was first given permission to hold a protest demonstration in Syntagma Square, which was abruptly canceled only to be permitted once again. As the demonstrators approached its headquarters in the square the police opened fire and many demonstrators were killed and wounded. In the days that followed ELAS forces attacked the city’s police stations and fighting broke out in many parts of the city between EAM-ELAS and Greek security forces and British troops.

On December 5 Churchill instructed Scobie to take decisive action (Churchill, “Triumph and Tragedy,” 289):

“You are responsible for maintaining order in Athens and for neutralizing or destroying of EAM-ELAS bands approaching the city… You may make any regulations you like for the strict control of the streets or for the rounding up of any number of truculent persons… Do not hesitate to act as if you were in a conquered city where a local rebellion is in progress…”

Despite the close relations between London and Washington, during the Dekemvriana the US Embassy and OSS remained passive observers but outspoken critics of the British. Ambassador Lincoln MacVeagh reported in his diary (“Ambassador MacVeagh Reports,” 660-661) that Alexandros Svolos, the EAM minister who had resigned from Papandreou’s cabinet, told him, “The British must give the Greeks at least the impression that they are a free people…” To President Roosevelt, MacVeagh wrote on December 8 that as he had feared for many months, “the disciplinary British and the unruly Greeks have at last come to blows.” He thought the problem was Britain’s “handling of this fanatically freedom-loving country (which has never yet taken dictation quietly) as if it were composed of natives under the British Raj… Mr Churchill’s recent prohibition against the Greeks attempting a political solution at this time, if a blunder, is only the latest of a long line of blunders during the entire course of the present war.” During the early days of the fighting in Athens, the head of the OSS in Athens, Gerald Else, wrote his superiors in Cairo that he could not “overstate my impression of the inflexible and yet bumbling way in which [the British] have handled this whole affair.” In a letter (Document 16) he noted that twice the British had “vetoed agreements reached by the government itself, which might have forestalled actual hostilities. The first time was when the government agreed that all Greek armed forces, including the Mountain Brigade, would be dissolved. Papandreou himself agreed to this, but Scobie forbade it. The second time was when Churchill forbade Papandreou to resign. Negotiations were already well along for [Themistoklis] Sofoulis to take over – God knows, a poor enough solution, but a Greek solution, and the Communists would have stayed in the government.”

In Washington, State Department officials echoed similar sentiments. In a draft memo for the president (Document 17), which was subsequently not sent, they wrote that “the situation in Greece is the tragic culmination of several years of inept but high-handed British intervention in the affairs of the Greek King and Government in exile. Despite our efforts to dissociate ourselves from this British policy, we are inevitably implicated in the public mind. To this day the King has given no definite promise not to return to Greece until after the plebiscite, and has refused to appoint a Regent in Greece. (Archbishop Damaskinos has been proposed and agreed to by all groups.) This would appear to be the basic reason for EAM-ELAS’ refusal to turn in in their arms unless the Greek Government’s Mountain Brigade and Sacred Battalion were simultaneously disarmed, a condition the Government rejected with British military support. There may be some grounds for EAM’s suspicions of the Greek ‘Army’ and its demand that this ‘Army’ be simultaneously disarmed, unreasonable as such a demand may appear on the surface. You will recall that the Greek forces in Egypt were purged of their EAM sympathizers (about two thirds of their strength) after last spring’s mutiny.

“Bloodletting is not the Greek way of doing things. There have been only two previous instances in recent Greek history: the execution of five Ministers and one General in 1922 under order signed by the present King; and the killing in Salonica of strikers by Metaxas police in 1936. Neither has been forgotten or forgiven. If the British keep Papandreou in power after Sunday’s apparently wanton shooting by the Athens police, worse troubles are bound to come.”

The KKE leadership soon realized that EAM/ELAS were unlikely to defeat the combined British and Greek forces. Already on December 6, EAM Secretary General Dimitrios Partsalidis (Document 18) told the EAM Central Committee that “by extending and prolonging the struggle the impression will be given, both in Greece and abroad, that the movement is very widespread and supported by a large section of the population. This impression, it is hoped, will eventually bring about Russian and American interference.”

“Even if there is little or no hope of victory against British forces.” Partsalidis urged continued resistance: “The extension of the fight will cause the maximum number of victims among the Greek civilian population and will thus engender a hatred of the British, which has never before existed. This they [he?] contended, would mean greater popular support of the KKE. Thus the way would be paved for Greece to come under Russian influence and join the Communist Confederation of the Balkans, to the detriment of British interests.”

Addressing the same meeting, KKE leader Yiannis Zevgos added that even if they were defeated by the British in southern Greece, the left-wing forces “will concentrate in Macedonia, which will be declared an autonomous state. ELAS considers that in Macedonia it will receive ample war material from Bulgaria.”

From Moscow on December 8 Dimitrov wrote (“The Diary of Georgi Dimitrov, 1933-1949,” 352-53) that he forwarded to Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov an inquiry from KKE leader Petros Rousos, who had recently arrived in Sofia, “Can assistance be granted to the Greek Com Party in order to oppose armed intervention by England?” The following day he wrote in his diary that he had “informed Sofia that in the current situation our Greek friends will not be able to count on active intervention and assistance from here. Also advised the Bulg Com Party CC not to become directly engaged [with] the beginnings of internal struggle in Greece.”

After the signing of the truce, the Greek military authorities captured three documents dated late January, 1945 (Document 19) from the KKE leadership of the Peloponnese. The first, dated January 19, is addressed simply to the Communist Party of Greece:

“Dear Comrades: Since the truce, the EAM Committee has left for Athens to negotiate with the Government. The basis of these negotiations will be to secure popular liberties, the purging of the army and State authorities of fascists, and to facilitate the elections by plebiscite. Since the alliance of the British with the opposition we are also asking for an Allied Committee to consist of American, Russian, British and French representatives to undertake the solution of the Greek problem.

“Apart from the above, our organization within British-held territory must continue to organize popular demonstrations for assurance of popular liberties, backed by financial demands. Similarly our organization must carry out the technical organization for adoption under the new conditions, as per instructions previously issued. The intransigence of the right based on unreserved British support might lead to a new conflict, in which case it is probable that the new campaign will take the form of guerrilla war, independent from city fighting. In all events our organization must start to sabotage the [Nikolaos] Plastiras mobilization. At the same time all measures must be taken to organize KKE ‘pirines’ in Plastiras units to carry out intensive enlightenment work. We must select from our men those of mobilization age, who are not known as Communists, and place them in the new Army, after training them in their duties. The difficulties of our present campaign, especially for our new members, have created a need among our organization an obligation to create faith, self-confidence and enthusiasm for our final victory. Victory will be ours.

“Destroy this letter as soon as you read it, but keep the points in mind. With Comrade Salutes, Party Committee for Peloponnese Area”

The second document, issued in Tripolis and dated January 17, was from the Peloponnese command to the Provincial Committee:

“Dear Comrades,

Previous Instructions have been issued to you for the creation of a secret illegal mechanism to secure the regular political guidance under any circumstances. We now give you the following instruction for immediate execution.”

Hereafter six orders are given which are summarized as follows:

“The requisitioning of houses with secret hideouts suitable for housing caches, ‘Yiafkes’ (Russian) houses or shops used as liaison points. The organization of clandestine printing presses with stocks of paper and various printing equipment. Instructions for the way in which underground propaganda and party machinery is to function. New members joining the party to be given good cover in order that they may be used as agents and their houses as rendezvous points. Women especially must be used as liaison agents. In organizing all this it must be borne in mind that we are ‘out of law.’ We shall continue the mobilization of the people for the defense of the Democratic liberties at the same time be ready to face all events. Special attention must be given to the creation of a democratic front which will instigate mass political work.

“Special care must be given to propaganda in all mass organizations, corporations, leagues and trade unions.

“Attention to the country district must be given in order to avoid the creation of armed opposition groups, and to the penetration of such groups from the Northern Peloponnese to the Southern Peloponnese. You must look after and attempt to enforce the system of governing committees.

“Destroy this document and inform us of its receipt. DEATH TO FASCISM – LIBERTY TO THE PEOPLE for the Peloponnese Committee. (Stamp of EAM)”

The third document, dated January 24, and signed by Thinios [ ]lacharas of the 2nd Bureau of the 3rd Division outlines the information sought by the KKE:

“1. Total enemy forces in various areas. 2. Details of commander of force. 3. Activity: Patrols, movements, methods of guarding barracks, store houses, and military offices, conduct toward citizens, organizations etc. 4. Armament: Details of rifles, automatics, guns, quantities of ammo, armored vehicles. 5. Transport: Number of trucks with their signs, animal transport. 6. Equipment: Food, ammo, arms, petrol stores and dumps. 7. Supplies: Where and with what means do they bring food and ammo from? 8. Fortification: Machine gun posts, FDPs, barbed wire etc. 9. Morale: Of officers and men. Feeling of officers and men. 10. Camping (What type of equipment?) 11. Signals: By phone, W/T, etc. 12: Shipping: Number of vessels in harbor on patrol etc. 13. Morale of organizations and of the people in the area. 14. Morale and activity of the opposition. The informer must give the place, time and source of information, checking each detail and give his appreciation. Information must be passed quickly and the informer must be discreet.”

In his diary on January 19, Dimitrov (“The Diary of Georgi Dimitrov, 1933-1949,” 352-53) wrote of a telephone call with Stalin, who told him:

“I advised not starting this fighting in Greece. The ELAS people should not have resigned from the Papandreou government. They’ve taken on more than they can handle. They were evidently counting on the Red Army’s coming down to the Aegean. We cannot do that. We cannot send our troops into Greece either. The Greeks have acted foolishly… The Yugoslavs want to take Greek Macedonia. They want Albania, too, and even parts of Hungary and Austria. This is unreasonable…”

On February 12, British intelligence (Document 20) said its “Athens representative has cabled us the following account of EAM/KKE relations with Tito and the Russians since the beginning of the revolt. This account is from a usually reliable Greek source, who has contacts with the EAM Political Liaison Bureau and who is convinced that his information is absolutely accurate:

December 8: Tzimas arrived in Salonica from Tito’s HQ.

December 10: Made speech assuring Tito’s moral support for struggle.

December 11: Met Siantos and Zevgos at Lamia to report results of his mission to Tito. Said Tito expressed sympathy, but would go no further without Russian consent for which he was not prepared to ask. Tito advised him to tell KKE CC to send delegates to Moscow.

December 15: KKE Committee decided to send Rousos, well-known Moscow trained Communist, to Moscow.

December 18: Rousos presented himself to Russian authorities in Sofia, who immediately put him under house arrest.

December 21: Rousos escorted to Greek frontier by Russians and returned Salonica and informed KKE of his misadventures.

January 13: KKE CC received communication (possibly through Tito’s HQ) informing them that Russians categorically disapprove of their policy and actions and reiterating directive given PEEA by Popov after split that KKE should remain loyal to State and participate in National Government.

In this connection [Evripidis] Bakirtzis observed to our informant on January 15 that KKE policy has been inexcusable since Popov had clearly explained the Russian attitude to Bakirtzis when he was President of PEEA.

Constantopoulos of EAM Political Liaison Bureau is visiting politicians in Athens declaring that the Athens Committee of EAM now regard the settlement as a foregone conclusion and look forward to resuming normal political activity soon.”

The question of why the USSR did not invade Greece continued to be discussed in KKE circles, even after their defeat in the civil war. “When questioned why from Bulgaria they did not proceed directly into Greece where Germans were present,” Tzimas reported to the KKE Political Bureau on June 16, 1951 (Vassilis Kondis & Spiridon Sfetas, 19-20), “It is said that the Soviets replied that it had been decided to reach Athens from the border ahead of the British, who had landed in Elefsina, but in his kindness Marshal Stalin submitted to Churchill’s pleas and compelled them to change direction toward Yugoslavia…”

The defeat of the KKE/EAM in the fighting in Athens and Piraeus ended the “Second Round.” Following the signing of the Varkiza Agreement, the Secret Intelligence Branch of the OSS on February 20 9Document 21) analyzed the political impact of the agreement and predicted that “the most significant effect of the agreement is that EAM, as a kind of second government, disappears from the stage, and responsibility for the next phase passes to the government and the British.”

The analysis continues: “Thus there is every reason to think that there will be no more hostilities in Greece this year, or even for several years. Both the British and the Left have reached a point in the road which leads steadily away from war. And the Right cannot make trouble without British support.

“The next move is up to the government and the British. If the agreement is honestly carried out, most of the acute maladjustments will gradually be eased. (Much also depends on the handling of relief and economic reconstruction.) There are still people on both sides who will try to sabotage the agreement. Much depends on the responsible top men – the British on one side and the high-ranking Communists on the other – to keep these malcontents from throwing the country into political turmoil. But in any case, it will be political turmoil, not war.”

To be sure, in seeking to understand the Dekemvriana readers may draw different conclusions regarding the historical significance of documents included in this collection. Yet whatever their views on particular aspects of the crisis it is likely they will agree that the outcome of the bloody conflict was determined not by Greeks but by the actions and inaction of the Allies, particularly Churchill’s Britain and Stalin’s Soviet Union. As EAM General Secretary Dimitrios Partsalidis observed decades later: “From the start, the CP of the USSR viewed with skepticism the outcome of the armed struggle… [Yet] the CP of the USSR could not decide to advise us to abandon the armed struggle… It only advised us to develop it with caution. We had no objection… (Partsalidis, “Dipli Apokatastasi tes ethnikis antistasis” [Double Restoration of the National Resistance], 200).

John O. Iatrides is professor emeritus of international politics at Southern Connecticut State University. He served with the Greek National Defense General Staff in 1955-56 and with the Office of the Prime Minister of Greece from 1956 to 1958. As a Washington, DC writer, researcher, and Greek-American community activist, Elias Vlanton has been deeply involved in US-Greek relations. He is the author of “Who Killed George Polk?”

Sources:

Document 1: September 9, 1944, 226-CID-L45704

Document 2: ASKI, Soviet military archives and records of KKE

Document 3: October 12, 1944, 226-CID-L47712

Document 4: November 26, 1944, 226-CID-L50414

Document 5: October 23, 1945, 868.00/1-2245 #427

Document 6: January 7, 1945, 226-CID-L52222

Document 7: January 7, 1945, 226-CID-L52219

Document 8: January 7, 1945, 226-CID-L52219

Document 9: January 7, 1945, 226-CID-L52219

Document 10: December 16, 1944, 226-CID-L51021

Document 11: January 7, 1945, 226-CID-L52219

Document 12: January 7, 1945, 226-CID-L52219

Document 13: January 7, 1945, 226-CID-L52219

Document 14: January 7, 1945, 226-CID-L52219

Document 15: December 16, 1944, 226-CID-L51021

Document 16: December 1, 1944, 226-210-WN10690

Document 17: January 8, 1945, NEA Memo, Lot Files

Document 18: January 5, 1945 226-CID-L51792

Document 19: March 11, 1945, 226-CID-L54716

Document 20: February 12, 1945, 226-CID-L53690

Document 21: February 20, 1945 226-190-Athens