British wiretapping and the King’s attempted coup against Karamanlis

An amazing story featuring the former king Constantine, his loyal adjutant Major Michalis Arnaoutis and the British secret services can be found in Konstantinos Karamanlis’ archives. It concerns plots to assassinate Karamanlis and to overthrow the democratic regime through a military coup. When the 12-volume “Karamanlis Archives” were published in 1997, they included the information that Karamanlis was informed in 1975 of a planned royal coup against him by Vice Admiral Spyros Konofaos, the chief of naval operations. Two years later, in 1999, Leonidas Papagos’ book “Notes – 1967-1977” was published. The ambassador and son of Alexandros Papagos, who had collaborated with Constantine, noted that Arnaoutis was planning a coup against Karamanlis in 1975 and had unsuccessfully attempted to involve Admiral Ioannis Vassiliadis in the conspiracy. Vassiliadis, who has passed away, as has Papagos, confirmed this information in 1999, immediately after the publication of Papagos’ book. Today Kathimerini reveals that the conspiracy was not momentary, but remained active for two-and-a-half years, and that, during its planning, even the possibility of assassinating Karamanlis and other politicians was discussed. It is a shady story which began in the autumn of 1975 and lasted until the beginning of 1978. What is also shocking is the revelation that the British secret services had installed a monitoring system to record Constantine’s conversations in London. And so they recorded him when he met with envoys of military officers who were conspiring in Athens and gave all the information – but not the tapes – to Karamanlis. The entire case was handled by the diplomat Petros Molyviatis, a long-time confidant of the Greek prime minister and his chief of staff.

Rallis’ information

Karamanlis was first informed of the former king’s steps to overthrow him by his minister Georgios Rallis in early October 1975. Navy officer Vassiliadis had told him that he had been approached by Constantine’s close associate, Arnaoutis, who told him that “a military movement was being set up to overthrow Karamanlis and reinstate the former king.” Arnaoutis assured Vassiliadis that Constantine “had already secured the intervention of the Shah to contain Turkey and that the Shah would also support him financially.” As Karamanlis himself wrote in a note included in his archives, a few days later another one of his ministers, Evangelos Averoff, was informed by General Ioannis Davos, the army chief of staff, that Arnaoutis had also approached a general. The flow of information continued with Chief of Naval Operations Spyros Konofaos notifying Karamanlis of similar moves by Constantine’s adjutant. [1]

Konofaos’ report

A report was given to then prime minister Karamanlis by the chief of naval operations, Vice Admiral Spyros Konofaos, who was one of the leading figures of the anti-dictatorial movement of the Hellenic Navy in 1973. Konofaos was informed by the fleet’s chief engineer, Captain Pierros Panagiotareas, that he had been approached by Arnaoutis in October 1975. He claimed that Greece had been cut off from the West and that Karamanlis’ government was “tolerating the maligning of the armed forces.” These developments “led a significant number of army officers, serving mainly in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, to the decision to intervene in order to save the country from the impending disaster,” stressed Arnaoutis, adding that “the former king also supports the need for such an intervention.” Arnaoutis also made it clear that “this intervention will be carried out regardless of the participation of the navy and the air force, and any reaction will be met by arms.” Constantine’s confidant foresaw that the coup would take place in February 1976 and that “it would be preceded by the political or physical elimination of the president of the government or by the conclusion of a humiliating agreement for Cyprus.” That is to say, they even envisaged the assassination of Karamanlis. The plan was that a referendum would be held, apparently to restore the monarchy, within 15-30 days, and parliamentary elections within eight months or so.

Panagiotareas and two other officers who attended the meeting with Arnaoutis expressed doubt as to whether the former king agreed with his adjutant’s plans. Consequently, Konofaos gave Panagiotareas permission to go to London and meet with Constantine on Monday, October 13, 1975. At this meeting, Konofaos wrote in his confidential note to Karamanlis, “the former king essentially confirmed what was said by Colonel Arnaoutis (retired).” There were some minor disagreements. The former king instructed Panagiotareas to brief Konofaos and to inform Arnaoutis of his reactions when he returned to Athens. However, Arnaoutis never came back to Athens, under the pretext that he was under surveillance, and he arranged a new meeting between Panagiotareas and Constantine in London on November 16, 1975. He made it clear there that the CNO was not even discussing participating in a coup and that the fleet would resist such an eventuality by all means. Constantine replied that since the air force also disagreed, he “would have no further involvement” and claimed that he had been visited by a representative of the American government, who said that the army, according to their information, intended to overthrow the Greek government, and expressed the trust the American government placed in him. Constantine added that the representative of the American government recommended that he should lead the armed forces in order to reduce the dangers involved. [2]

Panagiotareas’ note

In the briefing note that Panagiotareas wrote after the meeting with the former king at his home in London, he also stated that Constantine told him that he had “met with the British prime minister, who told him that in his opinion he would have to play a significant role in Greece again, because no other political figure, beyond Karamanlis, was in the picture.”

Constantine was distressed because he had traveled to Iran and Saudi Arabia to secure a 2-billion-dollar loan which he would use if he succeeded in being reinstated to the throne. Panagiotareas commented that the “king seemed disappointed and overwhelmed, in contrast with their previous meeting where he seemed determined.”

After receiving this information, Karamanlis sent Leonidas Papagos, who had previously been a collaborator of Constantine, as an envoy to London in early 1976. “I asked him to go to London and advise the former king to stop plotting,” Karamanlis wrote in his note, and continued: “Mr Papagos came back and told me that the former king had indeed met with Panagiotareas but that the conversation revolved around the overall situation of Greece and was not conspiratorial. The former king then called Arnaoutis and asked for information about the allegations against him. He confirmed that he had indeed had the meetings in Athens reported by Panagiotareas. Mr Papagos also told me that the former king was in a state of embarrassment and disappointment at the moment he conveyed my message to him.” [3]

The British inform Karamanlis

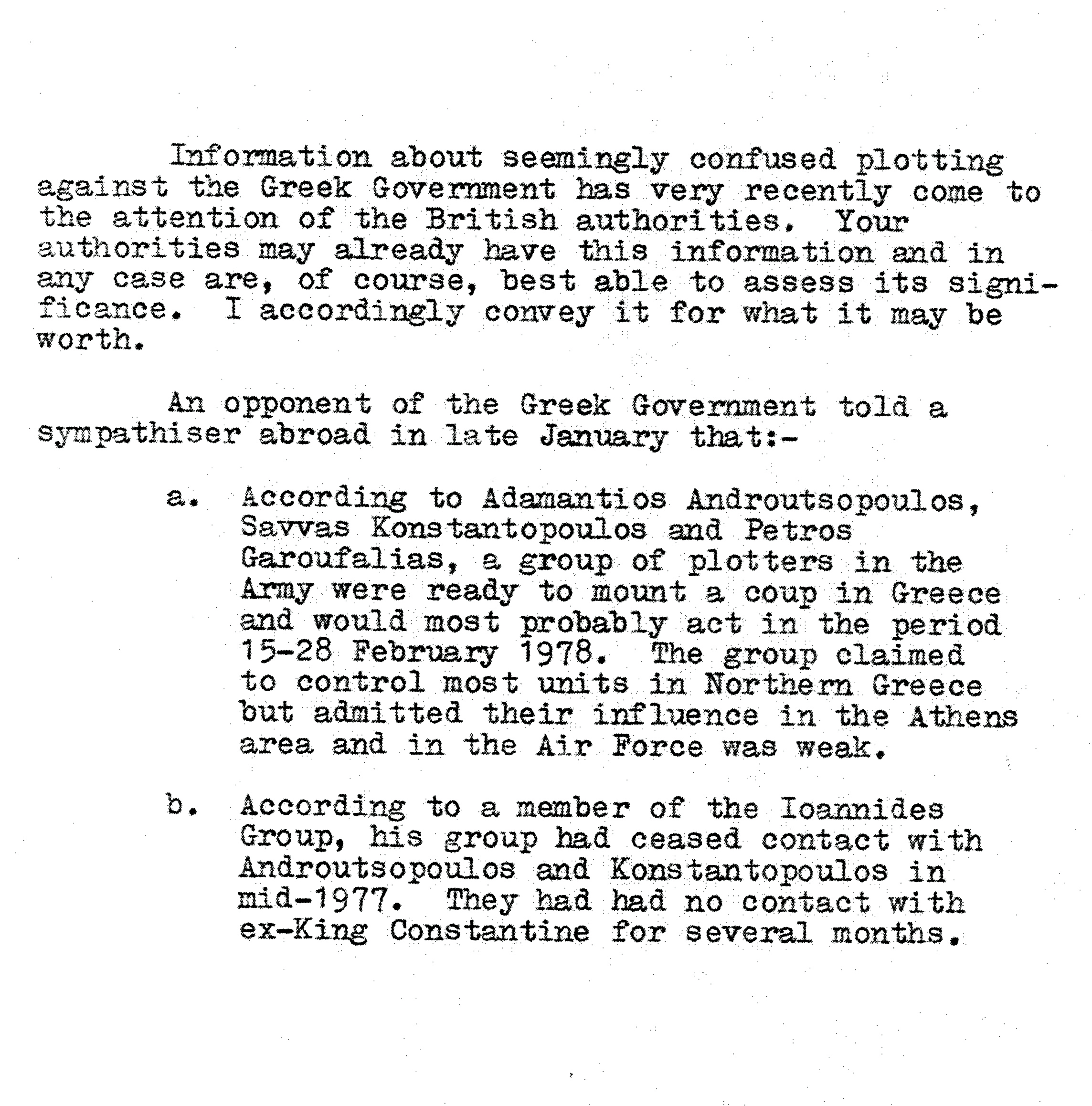

A few months later, on October 14, 1976, British ambassador to Greece Brooks Richards visited Karamanlis at his request and informed him that Constantine was in contact with conspirators in Athens and that he “does not have the initiative of the conspiracy, but is aware of it and certainly does not discourage it.” In a confidential note later written by the prime minister’s chief of staff, ambassador Molyviatis, he reported that, according to the British diplomat, “the British government does not know who the conspirators in Greece are. But they believe, based on their information, that the aim is to overthrow the regime, that they are fanatics and ruthless, and that their most probable method of action is political assassinations, with the prime minister being their first target.” The British ambassador concluded by telling the prime minister that, if he wished, “the British government is willing to make the necessary appeal to the former king in this regard.”

From that meeting on, a diplomatic and espionage thriller began to unfold.

October 21, 1976. The British ambassador paid another visit to Karamanlis and reported to him that the brother of the editor of Eleftheros Kosmos newspaper, Vassilios Konstantopoulos, had visited the king in London on behalf of a group of army officers loyal to Dimitrios Ioannidis. He told him that a coup was imminent, probably on November 13, as officers opposed to the government were to be dismissed immediately after that date.

The plan was to keep the units in the camps and arrest only senior officers. The conspirators were concerned “that there would be difficulties in the capital because the Left would spark a popular mobilization.”

Konstantopoulos, according to the British ambassador, told the king that “he would be notified a few days before the coup and should stand ready in London or another European city, when called upon.” The king, for his part, said he would get in touch with Konofaos to check the navy’s position, he anticipated that the United States, France, West Germany and England would react adversely, and that he believed the best date for the coup was November 2, the day of the American elections.

But the British ambassador made a shocking revelation at the end of the meeting with Karamanlis, for he assured him that “it is absolutely verifiable that the above was communicated between the former king and Vassilios Konstantopoulos.” In diplomatic and intelligence services jargon, this meant that the British services had secretly recorded the conversation, having obviously placed the necessary equipment in the former king’s residence, or having otherwise intercepted his telephone calls.

October 26, 1976. On Karamanlis’ order, Molyviatis went to the British ambassador and asked him for more information about Constantine’s meetings with Konstantopoulos. The ambassador revealed that Konstantopoulos said that “those on the move in Greece were junior officers and that they would carry out political assassinations. The former king asked for Mr Averoff, with whom he had an old friendship, to be spared.” The ambassador lastly told Molyviatis that he had notified the Americans of this information and that “all the information was provided on the personal orders of Prime Minister [James] Callaghan.”

On the afternoon of that same day, the second-in-command at the American Embassy, Hawthorne Q. Mills, asked for an urgent meeting with the prime minister and told him that they knew of the British information but could not verify it. He said, however, that the Americans were willing to assist the Greek government with an appeal to the king, if the Greek prime minister so wished.

October 27, 1976. Molyviatis invited the British ambassador to his office and asked him if his government would agree to the release of information about the conspiracy and the king’s involvement. He also asked “whether it would be possible, for our convenience, for them to give us the tapes from which we assume the information came.” The ambassador, Molyviatis wrote in his report afterward, “refrained from asking for instructions, but admitted informally that the tapes indeed existed.”

October 29, 1976. The British ambassador met with Karamanlis. He told him that although he did not yet have instructions, his government’s response would be negative both in providing the tapes to the Greek services and in making the information public. Karamanlis asked for Callaghan’s assistance in moving forward with the Greek investigations.

The British ambassador called Molyviatis sometime later and told him that he had suggested an “expert” be sent to Athens to provide all the evidence. He made it clear, however, that London did not want their information to be made public, nor did they want it to be known that it was from an English source, while the answer to the request to hand over the tapes of the king’s monitoring was negative.

November 1, 1976. The “expert,” apparently a member of the secret service MI6, Kenneth Parsons, attended a meeting with minister of public order Georgios Stamatis, the general secretary of the same ministry, Anastasios Balkos, Molyviatis and the British ambassador. The English agent gave a full briefing and revealed that Constantine and Konstantopoulos had also discussed the assassination of Karamanlis. Spyros Theotokis was to be appointed prime minister after the coup, while the officers involved in it were mainly under Ioannidis’ influence.

November 2, 1976. Molyviatis called the British ambassador again and asked that the British government make an appeal to the king making it clear that his “conspiratorial activities are not permissible on British soil.” But the ambassador replied that although London had offered to make such an appeal, it had “concluded that due to the family ties between the royal family of England and the former king, it would be better to have the Americans make the relevant appeal.” Molyviatis commented in his note to Karamanlis that this was apparently the reason why the second-in-command at the American Embassy in Athens had paid him a visit. And the British ambassador recommended that Karamanlis should ask the American ambassador to make the appeal to the king.

November 4, 1976. The British ambassador told Molyviatis that prime minister Callaghan himself had met with the former king “to make it clear to him the importance the British place on their good relations with the government of Mr Karamanlis and to warn him not to engage in any conspiratorial activity against the Karamanlis government while he remains on British soil.”

November 8, 1976. Molyviatis informed the British ambassador that the Greek government had sent a special envoy to the king, who told him that “they are aware of his activities and advised him to refrain from them in the future. The former king categorically denied the charges against him.”

18 November 1976. The British ambassador talked to Molyviatis and told him that Callaghan made the appeal to Constantine without giving any details.

At the end of Molyviatis’ note there is a handwritten note by Karamanlis saying “G. Rallis to London.” By that, it appears that Karamanlis also sent Rallis to the British capital to meet Constantine, who “denied everything.” [4]

The Greek attempts to record Constantine

Two years went by and it seems that Constantine did not come to his senses. In October 1978, Arnaoutis contacted retired General Georgios Tsichlis to arrange a meeting with the king in London. Tsichlis was joined by an associate of the Greek secret services, according to a confidential note by Balkos, the general secretary of the Public Order Ministry. This person apparently recorded the entire dialogue between Tsichlis and Constantine on November 14, 1978, without Tsichlis’ knowledge.

Constantine: How is the work of the committee going? (Note by Balkos: This is a committee of retired military officers and politicians with the mission of persuasion).

Tsichlis: Very well.

Constantine: Where do the ministers stand? Has anyone been persuaded?

Tsichlis: I got in contact with the minister for the presidency, [Kostis] Stephanopoulos. To no avail.

Constantine: Have you been in contact with [Ioannis] Davos and [Agamemnon] Gratsos?

Tsichlis: I saw them but unfortunately without result. (In the note Balkos writes: In our estimation he was lying again.)

Constantine (to himself): Both of them are brainless. Have you been in contact with the chief of the gendarmerie, [Miltiadis] Argiannis?

Tsichlis: No, I do not know him, not even by sight.

Constantine: Has the prefectural organization agreed upon now been completed? If not, it must be hastened. In January everything should be ready.

Tsichlis: Everything is going well. (Balkos’ note: He’s lying again.)

Constantine: When the commission travels to the United States to inform and influence the diaspora, I want you to be part of it.

Tsichlis: The committee has taken the decision to assassinate Karamanlis. (Balkos’ note: In our estimation and regardless of the fixed and additional measures, he was lying in a bragging manner.)

Constantine: For God’s sake, no such actions.

Tsichlis: The army is on our side. On this I have (Tsichlis’ brother-in-law) brigadier in office Kabouridis’ reassurance.

Constantine: What about the youth?

Tsichlis: …

Constantine: No answer needed. Greece’s youth is on my side… [5]

The decision not to make the case public

Konstantinos Karamanlis chose at that time not to disclose the information he had from the British and Greek services about the plotting activities of then king Constantine and Michalis Arnaoutis.

In a personal note that he filed in his archives, he wrote, “I avoided bringing this conspiratorial activity of the former king to the public, although I had an interest in doing so, both out of respect for the memory of his father Pavlos, and in order not to give the impression internationally that democracy in Greece is still precarious.”

1. Note by Konstantinos Karamanlis, Archives of the Konstantinos Karamanlis Foundation, 43-1402

2. Note by Spyros Konofaos to the president of the government, Archives of the Konstantinos Karamanlis Foundation, 43-1409

3. Note by Konstantinos Karamanlis, Archives of the Konstantinos Karamanlis Foundation, 43-1402

4. Note by the prime minister’s chief of staff, Petros Molyviatis, Konstantinos Karamanlis Foundation, 43-1416

5. Briefing Note for the Prime Minister, Archives of the Konstantinos Karamanlis Foundation, 43-1249