Tax fairness and elegance

Greek second round elections are due, and tax policy and tax fairness have become (purposefully) a campaign issue. Sadly, divide-and-conquer is polarizing the people and setting up parties against each other as though the other side is not worth a vote. It is not just in Greece where this strategy is popular.

Will my friends allow my opinion that this is inelegant?

What can be said with certainty, however, is that tax policy and tax fairness are important. How do we evaluate whether policies are efficient and just? Let us discount what politicians tell us in their campaign, and, instead, consult the data. Greece is part of the Euro (20). Eurostat provides helpful numbers. We don’t need to feel in a vacuum. Let’s compare Greece with partner countries that have helped it to emerge from the recession.

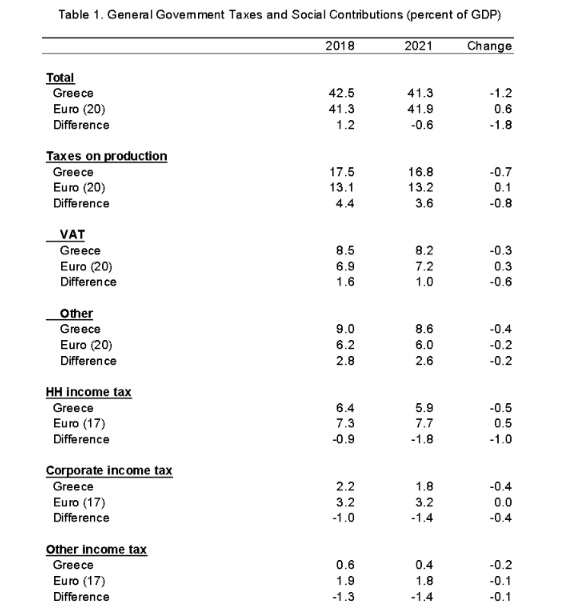

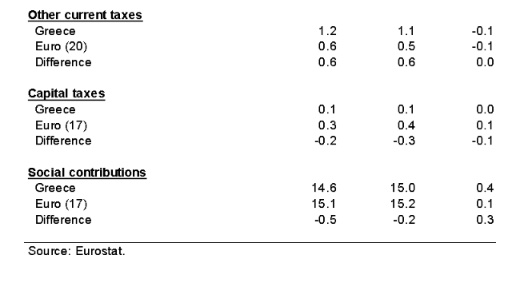

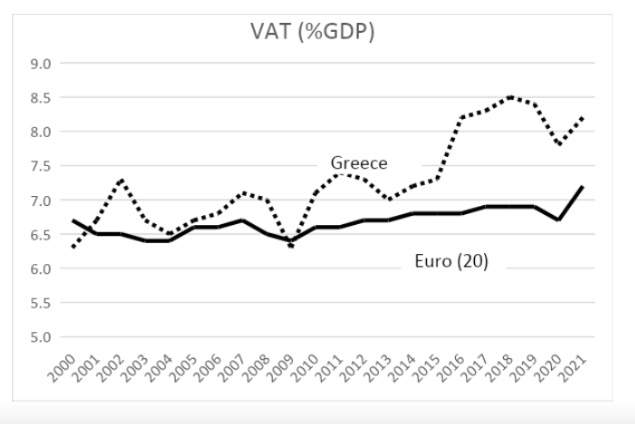

Eurostat’s national accounts data on “taxes and social contributions” show indicators for EU27 and Euro (20) countries:

– Greece is currently collecting less in taxes and contributions (%GDP) than the average Euro (20). For the country with the highest debt ratio in Europe, this appears inconsistent from a macro-economic point of view, because debt is postponed taxes.

– From 2018 to 2021 (one government to the next), total taxes and contributions declined by 1.2 ppts of GDP in Greece. They increased by 0.6 ppts of GDP in Euro (20). Greece benefits disproportionately from multiple supports from EU partner countries (funded by their tax payers), but is reducing its domestic tax effort. The other countries are increasing their tax effort to recover from the Covid and energy shocks (Ukraine), and to get their deficits and debts down, while helping Greece. All countries are subject to aging and productivity slowdown, just like Greece, so this difference in tax effort is striking.

Will my friends allow me to say, given these circumstances, that the tax-cutting rhetoric in Greece also is inelegant?

– Greece cannot afford to increase expenditure, even if paid for with new taxes. The deficits need to be reduced with carefully designed revenue gains and expenditure cuts (running a balanced budget; allowing automatic stabilizers to function). Debt is the result of spending that all are unwilling to pay for (Mr. Pangalos, RIP). Greeks love their children and grandchildren as in any country, but pass this enormous burden on to them at a time that natural resources are dwindling, and the environment is gasping. The liabilities that new generations face are much larger than even the registered debt. How do we assess intergenerational fairness if we play loose with deficit and debt problems?

Will my friends allow me to suggest that the hardship complaints of politicians, juxtaposed against the outlook for new generations, again, are inelegant?

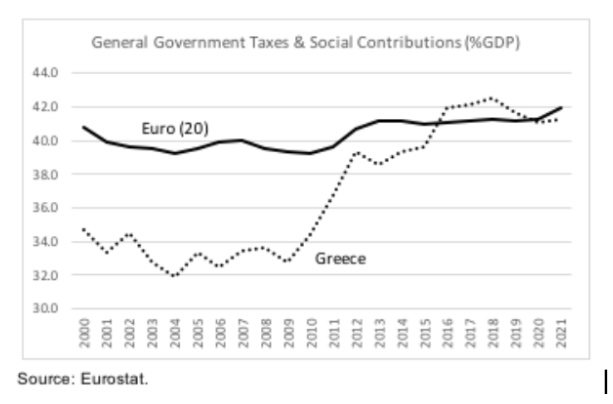

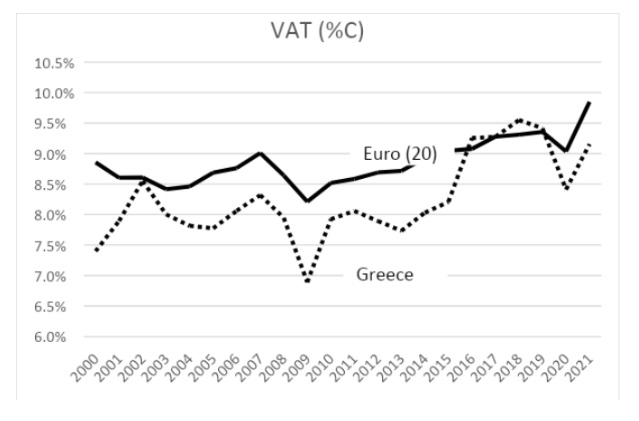

– Taxes on production, mainly VAT, generate more revenue in percent of GDP in Greece than in the Euro (20). This then becomes another issue in the campaign. But there is a catch… GDP is not the tax base for VAT—final consumption is. If we scale VAT receipts by consumption (Greek consumption is 90 percent of GDP; 75 percent in the Euro (20)), then we see that Greece collects less in VAT from the proper base than partner countries. Oops.

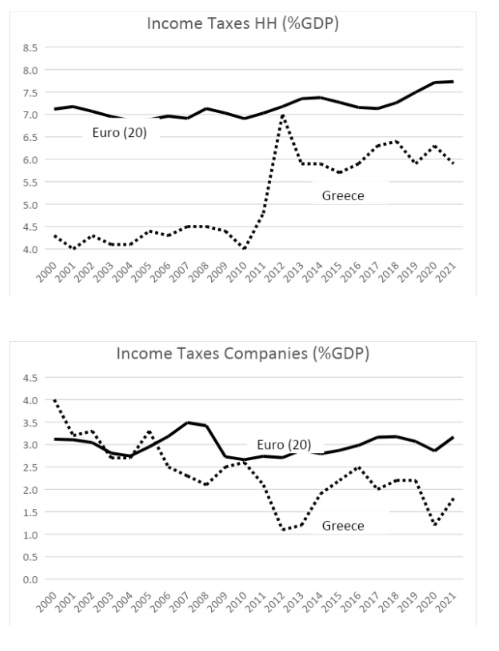

– Greece collects (much) less in income tax (%GDP) than the Euro (20). Household and corporate taxes are both below the Euro (20). Corporate taxes have declined proportionately more than household income taxes since 2018. We also know from the national accounts (income side) that the share of national income to labor has declined since 2018 (-1.4 ppts of GDP) as the share of operating profits has jumped (+4.0 ppts of GDP). A clever PhD student in Greece can write a dissertation on this, looking at efficiency and fairness.

– Greek income tax brackets have been frozen during the high inflation episode. This triggers strong “bracket creep” (inflation tax). Those subject to withholding cannot escape.

Public finance experts agree that this is inelegant.

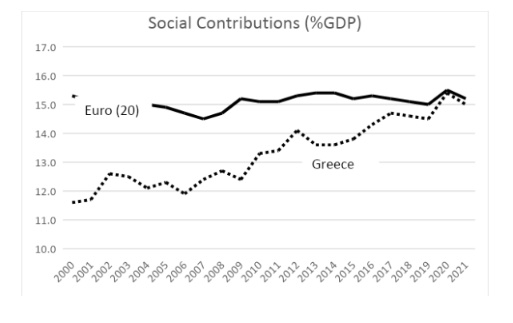

– Social contributions have gone up in Greece in relation to GDP; staying about even in the Euro (20). This results of higher employment (an achievement for Greece to celebrate and continue), and bracket creep. Greece has almost caught up with the Euro (20) in social contributions to GDP, even though its inactivity rate is higher than in the Euro (20), and hence the funding need bigger.

These numbers only scratch the surface of the complex and delicate issue of taxes and burden sharing. Economists can talk about tax efficiency. Tax fairness is more complex and needs to be discussed in the political process. Greece needs independent institutions that can give citizens a view on what is going on, how domestic developments differ from those in partner countries, and notions of fairness vis-à-vis: (1) domestic tax payers, (2) partner countries, and (3) young generations. This independent analytical view is underutilized, so the voters are like the lambs before the wolves in politics.

With Greece reducing its tax effort, while young people worry about their future, will my Greek friends forgive me if I say, as a foreigner who lives far away in a country that is also victim of unpleasant political maneuvers, that all of this is not good for Greece, and, furthermore, inelegant?