‘There’s no place for us in this amusement park’

Owners of old shops in the center of the capital are feeling the pressure of expanding tourist entertainment and accommodation businesses

“We’re fighting tooth and nail to stay open,” says Yiannis Karayiannis, the owner of Astron, a glassware and porcelain store on Voulis Street, just off downtown Syntagma Square.

“We’re thinking of liquidating at the start of the year,” Spyros Katoumas, owner of the Radio Katoumas electronics store on Praxitelous, tells Kathimerini.

For Lena Kalyvioti of the Kalyviotis haberdashery on Ermou, “carrying on is only for sentimental reasons,” while Vassilis Masselos, CEO of the Nota lingerie store on the corner of Akadimias and Voukourestiou, says the business would have already closed if it had been paying rent.

Athens is changing; it is being gentrified and modernized. But what happens when such progress erodes its fundamental character? What happens when outrageous rental rates or changes in building usage push out historic businesses?

“When I came into the business in 1985, Praxitelous was full of textile merchants and it was a thriving business at the time because many people had their clothing made for them,” remembers Masselos. “When we wanted electronic goods, we went to Leocharous Street, and for doorhandles it was Vissis. Today there are maybe four of five such businesses left in the city.”

These small business hubs have gradually dried up and all but died.

“Businesses cannot afford the rent anymore as Athens is turning into a giant hotel-Airbnb-bar, and this is coming at a cost, even though no one seems to be taking notice. The businesses replacing retailers and manufacturers cause a slowdown that is not being accounted for. If the city center keeps making way for tourism activities, moreover, it will inevitably lose its attractiveness. You can’t plant 50 eggplants in the same pot and expect them to survive. We need a different policy,” says Masselos.

When Nota opened in 1975, Voukourestiou was lined with well-established Greek shops. “With very few exceptions, the street has nothing but international brands now. The Greek element is almost entirely absent. Other cities face the same kind of pressure, but in London, Paris or Rome, you will mainly see iconic local brands. This is not the case in Athens, unfortunately,” Masselos adds.

The story was the same on nearby Ermou Street. Occupying the same address since 1956, the owners of the Kalyviotis haberdashery have borne witness to everything from a king’s funeral to mass anti-austerity protests.

“This used to be the street for goods stores carrying homeware, clothing and shoes,” remembers Lena Kalyvioti. “Then Ermou filled with shoe stores and lost its variety; then Athenians found it harder and harder to get downtown because of traffic jams and then because of traffic restrictions; then the big chains swept in and pushed out the traditional businesses; and then there were big protest rallies all the time. It has become incredibly difficult to survive right now, but the crisis in the city center is not new. It started many years ago,” she says.

Protest rallies, riots (many businesses in downtown Athens cannot even secure insurance), rental rates, and competition from big chains forcing smaller businesses to stay open for longer hours make for a very difficult mix. “We’ll hang on as long as we can,” adds Kalyvioti.

And what about new businesses that are not related to tourism? It took Andreas Kokkinos and Stathis Mitropoulos more than a year-and-a-half – and that during the peak of the pandemic – to find a suitable space to open a bookshop specializing in art, design, photography, architecture and fashion, something which was missing from the area. “It was so disheartening. The rents were exorbitant, even for pokey little spaces. How can you possibly afford that, unless you’re selling diamonds or gold?” asks Mitropoulos, adding that many ground floor business spaces were also closed in buildings that were bought up for hotels.

“Many of the spaces we saw back when we were looking are still shuttered. The owners obviously aren’t interested in finding tenants,” says the owner of Hyper Hypo, which now lights up the once-dark doorway of 10 Voreou Street, between Monastiraki and Omonia.

Masselos stresses the need for a comprehensive new policy – and fast – while warning of the “catastrophic” impact of a government plan to transfer dozens of state services to a former industrial complex in the suburb of Dafni. “The city center is being transformed into an amusement park for tourists, like Las Vegas. In my opinion, incentives need to be provided for people to move back into the historic center as residents,” he adds.

Sideris, watch repairs, since 1928

‘I’ll have to move if the rent goes up’

Three generations have set their watches by the clock in the corner of the workshop. “My grandfather bought it at some point; my father hung onto it and so did I,” said Nikos Sideris, who stepped into the family watch repair business in 2001. “That clock has been with us for nearly a century.”

Three generations have set their watches by the clock in the corner of the workshop. “My grandfather bought it at some point; my father hung onto it and so did I,” said Nikos Sideris, who stepped into the family watch repair business in 2001. “That clock has been with us for nearly a century.”

His grandfather moved to Athens from the island of Naxos, learned the craft and opened his first store on Agis Irinis Square, before settling at 8 Voulis Street in 1928.

Sideris had no qualms about studying the craft and carrying on the business. “I love it,” he says. “Watches that need to be mended or restored are sent to me from all over Greece. I even get a few pieces from abroad. We don’t just fix watches that are seen as a tool, but also watches that are memories. A family’s entire history can be encompassed in a watch.”

The biggest problem he faces today, is rising rental rates. “They didn’t even fall during the crisis here in Syntagma, and even then they were sky-high. I’ll have to move if it comes to that. I hope that my customers will still be able to find me, but right now I have people dropping by with their fathers, telling me that they remember my grandfather or that they saw my shutters closed one day and got worried. I think of myself as a small part of what makes Athens so beautiful and charming.”

Diplous Pelekys, Greek arts and crafts, since 1925

‘All you see is tourists’

Impressed by the excavations at Knossos in her native Crete, artist Florentini Kaloutsi decided back in the early 1910s to create a series of textiles with Minoan art motifs and to revive the traditional craft of loom weaving. The endeavor was such a success, she opened a workshop with 150 looms and special areas for dyeing, sewing and ironing her wares in what was one of the earliest cottage industries in Greece. She called it Dilpous Pelekys (Double Ax) and the name still hangs today over Athens’ oldest Greek folk art store.

Impressed by the excavations at Knossos in her native Crete, artist Florentini Kaloutsi decided back in the early 1910s to create a series of textiles with Minoan art motifs and to revive the traditional craft of loom weaving. The endeavor was such a success, she opened a workshop with 150 looms and special areas for dyeing, sewing and ironing her wares in what was one of the earliest cottage industries in Greece. She called it Dilpous Pelekys (Double Ax) and the name still hangs today over Athens’ oldest Greek folk art store.

It was originally located in Karytsi, then spent 40 years on Voulis Street and has now been in the Bolani Arcade since 2004 – always around Syntagma Square. “The last move happened when the rent sky-rocketed,” says Katerina Grapsa, Kaloutsi’s granddaughter.

“As things got harder, we stopped carrying woven textiles and gradually moved into objects d’art and jewelry. But we still get elderly women coming with their grandchildren and reminiscing on the old days,” she says.

After 40 years in the business, Grapsa is not optimistic about the future. “All you see is tourists with a phone in their hand looking for their Airbnb. Sure, money may be coming in, but it’s not keeping the residents here. Instead, all you have is bars, souvlaki joints, twisty fries and I don’t know what else. But there’s something very wrong when there’s no balance between natives and visitors. If state buildings are also turned into hotels, then you can forget the city center.”

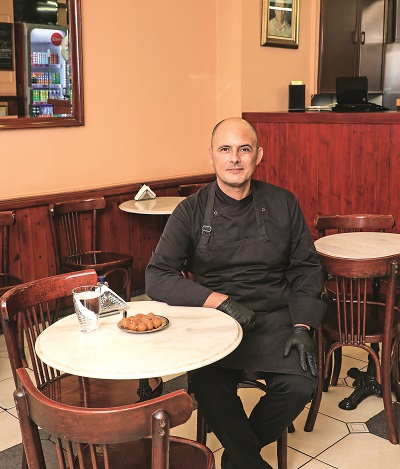

Ariston, bakery, since 1906

‘Athens is in a phase of rebirth’

“I have so many great stories, about old clients, new ones, others that came back to us after 10 or 20 years, people who live in America or Canada and came looking for us after hearing about how great our pies are from their relatives.” Aged 22, Dimitris Panagiotopoulos is the proud fourth-generation owner of Ariston. Located on the ground floor arcade of the listed Merchants’ Fund building at 10 Voulis Street, the business has been spared the fate of others thanks to the fact that the building is listed and the retail spaces inside it protected from being used for other activities.

“I have so many great stories, about old clients, new ones, others that came back to us after 10 or 20 years, people who live in America or Canada and came looking for us after hearing about how great our pies are from their relatives.” Aged 22, Dimitris Panagiotopoulos is the proud fourth-generation owner of Ariston. Located on the ground floor arcade of the listed Merchants’ Fund building at 10 Voulis Street, the business has been spared the fate of others thanks to the fact that the building is listed and the retail spaces inside it protected from being used for other activities.

Ariston’s “kourou” cheese pie – named after the Turkish word for “dry” thanks to its crumbly crust – continues to be the best-selling item on the list of more than 40 sweet and savory pies this historic bakery produces.

“We’re constantly refreshing the menu, bringing back old recipes, creating new ones and changing with the times,” says the young owner, who practically grew up surrounded by heaps of flour and mounds of butter.

“Unfortunately, the Merchants’ Fund has been empty for the past few years, while some worthwhile efforts by the municipal authority to revive the arcade have failed to yield results,” says Panagiotopoulos, who still describes himself as a “natural optimist.”

“The crisis obviously affected everyone and everything, including, of course, the city center. But capital cities change and evolve. It is sad to see so many decent businesses close, but I believe the city center is in a phase of rebirth.”

Astron, homeware, since 1949

‘Every new business is a bar’

We visited Astron the day of a general transport strike that brought Athens to a halt. “My son and I thankfully live nearby and walk to work,” says Yiannis Karayiannis, the 59-year-old owner of the homeware store at 4 Voulis. “You should know that this was another reason why so many old shops in the historic center closed.

We visited Astron the day of a general transport strike that brought Athens to a halt. “My son and I thankfully live nearby and walk to work,” says Yiannis Karayiannis, the 59-year-old owner of the homeware store at 4 Voulis. “You should know that this was another reason why so many old shops in the historic center closed.

Their sales suffered because so many days of business are lost for reasons like this. Take today, for example. I bet the shopping centers in the suburbs are full of people. In the 30 years that I’ve been in this business, not a single government has done anything to support the small business owners in the city center. We have been in this same spot since 1949, but the truth is that we’re fighting tooth and nail to stay open.”

Karayiannis’ face lights up as he starts talking about his merchandise, the porcelain and crystalware, the rare collection in the basement, which, he describes as an “open museum.” Among much more, it boasts the Road to Windsor dinner service by Johnson Brothers, bearing Queen Elizabeth II’s warrant.

“Young people are turning to quality again, thankfully. They didn’t want all this stuff when they saw it their parents’ home, but that’s changing gradually. That’s what we’re betting on. On that and on social media, because we no longer have the number of customers we used to. People back then said that I was lucky to have a store in downtown Athens, but that’s not the case anymore. The afternoon rush is gone. People only start coming at 8 p.m. for the bars. Every space that’s vacated becomes a bar instead of a shop,” he says.

Ktistakis, loukoumades, since 1953

Renovations, but not for residents

When Thodoris Ktistakis, owner of the self-named cafe on Omonia Square’s Sokratous Street renowned for its deep-fried loukoumades donuts, read that the nearby Damigos toy store was being forced to move, he got worried.

When Thodoris Ktistakis, owner of the self-named cafe on Omonia Square’s Sokratous Street renowned for its deep-fried loukoumades donuts, read that the nearby Damigos toy store was being forced to move, he got worried.

“When your neighbor’s house is on fire, you’re next,” he tells Kathimerini. “We’re safe for the time being, but you never know. The charitable foundation that owns our building is looking for an investor to turn it into short-term rental units. We’re watching it happen all around us. It’s brutal. They give you two months to pack up and go.”

After learning his trade in Alexandria in Egypt, Ktistakis’ grandfather – also named Thodoris – started selling loukoumades in Hania on Crete in 1912. The family moved to Athens in 1953 and opened a store on Agiou Konstantinou Street before moving to Sokratous in 1996. “That’s why when people ask me where I’m from, I say Omonia. I’ve been here for 51 years,” he says.

Ktistakis is torn about the changes taking place around him. “It’s lovely to see abandoned buildings being restored, but the number of residents is dwindling. And the residents are what give a place its local color,” he says.

His cafe is starting to be discovered by tourists. “They’re coming to Omonia and the loukoumades are one of the reasons. They’re not as scared [of the area] as the Greeks are. I personally think the city center is safer than the suburbs. It’s just that Athens is honest, it hides nothing, and that frightens some people.”

Lido, pastry shop, since 1967

Flavors of Asia Minor in Pangrati

Kifel are small crescent-moon shaped pastries originating from Asia Minor made with a dough that is something between a bread and a croissant, and stuffed with chocolate and walnuts. The big tin trays of fragrant kifel are but one of many reasons to open the trademark door of Lido, which lets out a blast of Eastern aromas into the air of Pangrati every time.

Kifel are small crescent-moon shaped pastries originating from Asia Minor made with a dough that is something between a bread and a croissant, and stuffed with chocolate and walnuts. The big tin trays of fragrant kifel are but one of many reasons to open the trademark door of Lido, which lets out a blast of Eastern aromas into the air of Pangrati every time.

“We still import the mahleb from there,” says Petros Piperidis, the grandson of the Petros Piperidis who opened the pastry shop at this exact location back in 1967. He had owned a similar store in Istanbul but was forced to abandon it in 1965 when the Greeks were expelled from Turkey. He had first got a job at a pastry shop in Athens in order to get an idea of the market here and then opened his own store at 35 Chremonidou Street.

“He did a brisk business from day one. All of his recipes, but also his ingredients, were from Istanbul. The tsoureki was, of course, his bestseller. He only made it at Easter at first, but people liked it so much, he started making it every day,” the younger Piperidis recounts. Lido has been doing the same thing ever since, using the same exact recipe.

Even some its suppliers have remained the same, like “the guy who brings us marmalade, ION, where we get our chocolate, and others.” “When you’ve worked with someone for 50 years, it’s not longer a buyer-supplier relationship, it’s a friendship,” says Piperidis, who’s has been at the helm of the family business since 1998.

The owners of the property where the store is located have also remained unchanged for 60 years. “We’ve been together from the start; it’s just the generations that have changed,” he says.

Radio Katoumas, electronics, since 1960

Proud to be debt-free

The store that once helped light up almost every home and business in downtown Athens may soon be switching off its own lights for good. Spyros Katoumas, the son of Radio Katoumas founder Michalis, is losing faith as he watches other stores go out of business on Praxitelous Street to be replaced by bars, cafes and eateries.

The store that once helped light up almost every home and business in downtown Athens may soon be switching off its own lights for good. Spyros Katoumas, the son of Radio Katoumas founder Michalis, is losing faith as he watches other stores go out of business on Praxitelous Street to be replaced by bars, cafes and eateries.

“There used to be 12 stores selling electronics and electrical appliances on this tiny street. Now it’s just us and another smaller store – Baven – down the way,” the 65-year-old businessman tells Kathimerini.

Michalis Katoumas opened his first store, a small business, at 14 Praxitelous in 1960, selling a few innovative items. It did so well that he moved to a bigger space at Number 23 four years later, and then outgrew that too in 1970, moving into much bigger premises at Number 15-19, where it remains to this day. The time has come to call it a day, though. “The businesses in the area have changed, and so has the clientele. All three floors above us are Airbnbs; it will be time to go soon,” says Katoumas.

And that’s not all. “Needs have changed too; people no longer repair things and the industries have closed; nothing is made in Greece anymore. There was a time when we supplied major factories. Our turnover has shrunk to one-twentieth of what it was in 2000.”

His children have also chosen a different path, so his decision will be final. “The economic hits have been successive, and I am proud that we survived debt-free. But I have been in this store since I was 7 years old. It’s very sad…”

All of the portraits are taken by Nikos Kokkalias for Kathimerini.