Documenting history as it happened for 30-plus years

“I remember something and travel somewhere every day. I thank God I’m alive every morning when I wake up because I’ve seen so many of my colleagues killed,” admits Aristotelis Sarrikostas. The acclaimed veteran photographer of the Greek desk of The Associated Press is relaxed as he sits in the office of his southern Athens home, glancing every so often at the news website page open on his computer screen.

Keeping abreast of Greek and international developments is one of the daily habits he hasn’t shed since retiring from a job that sent him from the Athens Polytechnic for the 1973 uprising against the junta to war zones in the Middle East, armed with his favorite cameras (search as I may, I don’t see any evidence of them in his office room).

“I’ve put them away so they don’t gather dust,” he says with a slightly bitter smile.

With his well-kept mustache and gray wavy hair, Sarris, as he is known to his non-Greek colleagues, seems ready to set off for another mission for the US-based news agency, despite his 82 years. “I’ll admit that I often think about grabbing my camera and heading out, but there’s a time for everything.”

It is said that photojournalists are camera-shy, and indeed, there are only a handful of photographs of Sarris in action in a new book published by Menandros, “Zin Epikindinos” (A Life Lived Dangerously), on the part of his career stretching from the 1960s up until 1997, when, he says, he took a long leave of absence. In these, Sarris is seen holding a 12-exposure Rolleiflex or the boxy Graflex he used when covering sports events, and later his first Nikon film cameras, technology that seems almost inconceivable today, when his colleagues take thousands of shots to capture every single moment of any event.

“I’m not sure I could work today,” he admits. “To begin with, you don’t have a sense of the photograph. In my day, there was an entire process that came after the click of the shutter. You had to use a darkroom, to develop your film by hand, to dry it, to make the photograph lighter or darker depending on the effect you wanted; it’s not at all the same thing anymore.”

Power of the image

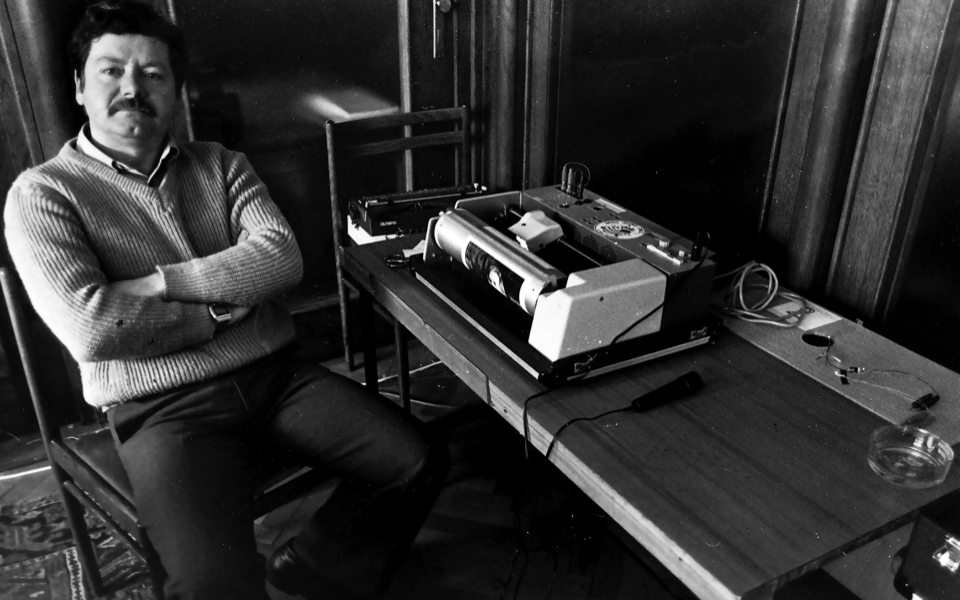

In one of the images we see him sitting beside the Muirhead wirephoto scanner he used to send his shots to the AP desk in the United States, something similar to a fax machine but for images. This allowed him to send photos of Greece from Athens to the rest of the world, images that would have a positive or negative impact on public opinion and, by extension, on policymaking.

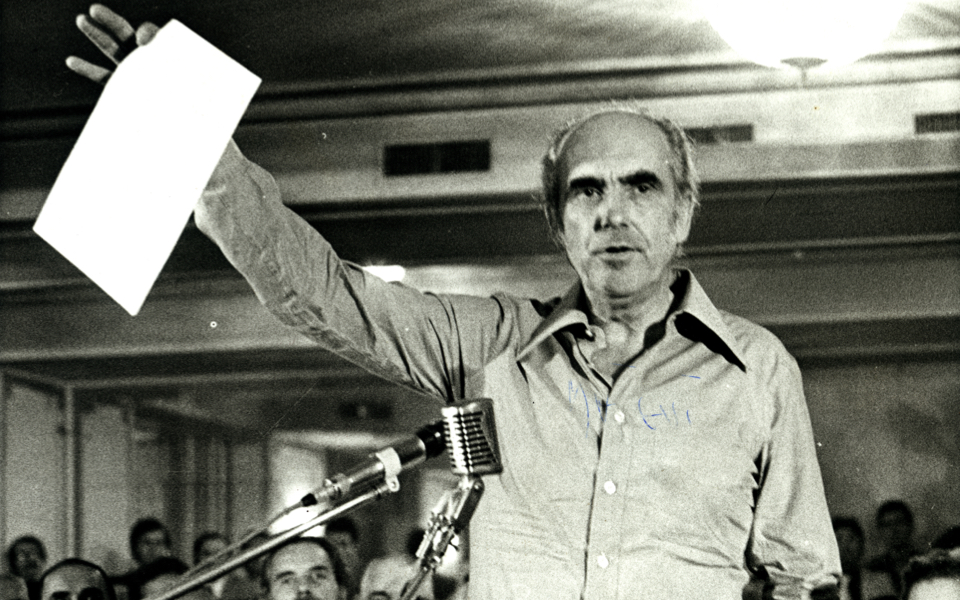

The undisputed power of the image is something he saw proven time and time again. For example, a shot from 1967 of King Constantine swearing in the junta government that was published by AP was enough to cost the sovereign his power, as Sarris writes in his book. “Photographing major events is different when you’re at home and when you’re abroad. Here, your emotions get involved, but abroad you have more aplomb. The 114 youth riots in the 1960s and the student uprising against the dictatorship in 1973, for example: scenes of policemen beating students, cracking heads open, making arrests, these are things that upset me but I knew I had to document them. You can’t do any different and that’s why I was there after all. Many people call us ‘vultures,’ but it’s not true – we have feelings. That’s what photography is: documenting reality,” he says.

Polytechnic uprising

It took about 20 minutes to send an image using the wirephoto scanner, and if something went wrong, you had to start the entire process all over again. He used the machine to send his photographs of the tank breaching the gates of the Athens Polytechnic on the night of November 17, 1973, images that were seen all over the world the following day. The then 36-year-old photographer was standing right beside the tank when it rammed the university’s gate. “I could hear the sergeant on the tank saying, ‘Yes, yes.’ Then I saw the turret rotating and the tank backed onto the same sidewalk I was standing on. It accelerated all of a sudden and crashed into the gate of the Polytechnic. I was shocked, but I pulled myself together and ran out into the middle of Patission Street to get a better shot. If it weren’t for me and Belgian correspondent Albert Coerant, who was there with a Dutch TV crew hiding in the Acropole Theater, we would not have any images from that event,” Sarris recalls.

“I remember that Vassilis Karamanolis, who worked for the Mesimvrini newspaper, turned up a bit later, around midnight, and he signaled me that he was leaving for the paper. I managed to shoot off three frames, without a flash, and a bit out of focus, before two policemen rushed me, wielding sticks instead of clubs. I used to box at the time, so I managed to dodge most of their blows but I did get hit in the hand. When I saw them reaching for their guns, I ran away as fast as I could to the Academias Street office and sent the photographs through.”

Sarris was awarded the Golden Cross of the Order of Honor by President Karolos Papoulias in 2008 for that historic moment.

The last straw

Sarris’ lens captured stars and famous personalities, as well as events that galvanized the world. Taking a sip of coffee, he remembers photographing The Beatles during a visit to the Mount Parnassos resort of Arachova, Jean-Paul Belmondo walking around Plaka with Ursula Andress, shots of Melina Mercouri, Giorgos Seferis and Odysseas Elytis, of Marlon Brando on the Acropolis, or of that summer day in 1970 when he captured Christina Onassis in a loose white tunic, getting ready to dive into her pool in the seaside suburb of Glyfada. “We hadn’t been invited in and weren’t allowed inside the house. But we got our shot before we were chased away,” he says, laughing at the memory.

The photojournalist’s job is to put the subject above everything, come what may. “Whether in a war or at a protest rally, coverage is what you’re there for. Being in a war zone is intense, because you’re scared for your own life. But can you allow your emotions to stop you when you’re there to take photographs? No, otherwise you’re not cut out for the job. You may look back on it later and wonder at what you did.”

As an Associated Press correspondent, Sarris covered the Arab-Israeli conflicts of 1967 and 1969, the civil war in Lebanon, clashes between Israelis and Palestinians in Gaza, the abduction of The Associated Press’ chief Middle East correspondent Terry Anderson in Beirut and the Iraq-Iran War in 1980.

Did he ever allow his emotions to get in the way?

“That happened once, with my little hero,” Sarris admits. It was in Lebanon, in Sidon, where he came across three boys who were the same age as his three sons. Laden with ammunition, they were trying to cross an olive grove through a hail of bullets from the Lebanese, Israel’s allies, to reach a group of Palestinian fighters. The Greek photographer left at some point, but the boys carried on. “You have no reason to risk your life, but we have to get these bullets to the fighters,” one of the boys had told him. A few hours later, Sarris was taking photographs at a hospital when he saw the boy’s lifeless body lying on a stretcher. “I felt worse than I have ever felt in my life in that moment. It still really pains me to think about it. I couldn’t eat for three days and even though I kept taking photographs it was like I’d checked out. My mind was somewhere else, with my own children. It took a toll on me,” he says, recalling the incident.

A storied life

Aristotelis Sarrikostas’ life reads like a novel. There were a lot of twists and turns in the road that eventually took him to The Associated Press, an achievement that probably would have seemed impossible to the young boxer who fought in the rings of Brazil in the 1950s.

Born in the Athens neighborhood of Kaisariani in 1937, the youngest of five siblings, Sarris lost his father in 1941. In the book, he describes the hardship and hunger of the occupation and the ensuing Civil War, and the reasons why he decided to set sail for Brazil at the age of 15. His aim, however, was America, and with this in mind he left his brother-in-law’s Greek restaurant in the South American country and got a job as a deckhand on a Greek oil tanker. On his second trip to the United States, he abandoned ship with the captain’s consent, and, gripped with the anxiety of every illegal migrant, took a bus to Seattle. He spent some time in hiding and later got a job with some relatives in California.

He decided to return to Greece at the age of 18 to complete his military service. His mother did everything in her power to keep her boy at home. One of those moves was to introduce him to Kleisthenis Daskalakis, a neighbor who was also a well-known photojournalist and a partner in the photo agency Enosis. In his book, Sarris admits that he asked the photographer to tell his mother he wasn’t cut out for the job after a couple of weeks. The weeks soon turned into months and the young man who dreamed of returning to America stayed in Greece. He did, however, travel all over the world for the next 40 years.

Life not lived

The view from the top-floor Glyfada apartment he shares with his wife is quite stunning. I ask the veteran photojournalist of the life he hadn’t lived while he was away for weeks and months on assignment. “That’s the price you pay. Even though she doesn’t like me saying so, I think my wife was a hero. She was a mother and a father to our three children – she raised them. But I don’t feel like I had a choice. I couldn’t stop. I would get restless within a week of coming back from some tense locations. I would relax as soon as the phone rang with a new assignment,” he says, describing the “addiction” of many war correspondents.

“I am happy to be alive and breathing,” he says as I get ready to leave, taking a quick glance at his phone. “I still wait for it to ring, but it doesn’t.”