An affair with a love letter, ‘Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold’

With more than 50 years' worth of essays, novels, screenplays and criticism, Joan Didion has been the premier chronicler of the ebb and flow of America’s cultural and political tides with observations on upheavals, downturns, life changes and states of mind in epoch-making books, including “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” “Play It as It Lays” and “The White Album.” She wrote about her reckoning with grief after her husband’s death, writer John Gregory Dunne, in “The Year of Magical Thinking” (winner of the 2005 National Book Award for Nonfiction), and the death of their daughter Quintana Roo, in “Blue Nights.”

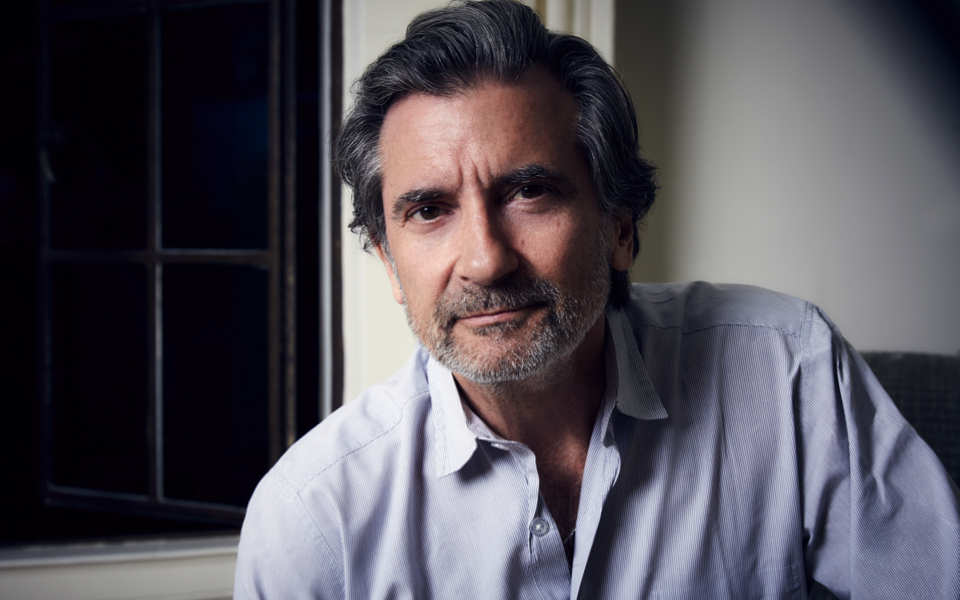

US-based Greek writer Ioannis Pappos dives into the highly anticipated and recently launched documentary, “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold,” and discusses with its creator, actor and director Griffin Dunne, this “love letter” to his “Aunt Joan,” how was it growing up within such a zeitgeist-influencing family, and the world today through those Didion dark glasses.

Ten minutes into “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold” (Netflix) and the viewer already has the key influencers to the character shaping of the film’s subject: Didion’s ancestors' rough settling roots in Sacramento, California, her subconscious hold on the Donner party (in her first essay, age 5, her heroine dies of cold and/or heat), her real and figurative fear of snakes, her longing for a John Wayne type protector (a figure that will show up as an imaginary husband in her work) as well as an elusive yearning for a Wayne-like American morality.

The film follows Didion’s life as she moves east, into the excess and the literary wannabe circuits of New York City. Then back to California, this time Los Angeles, during the disorder of the late 60s, which turns, as often disorder does, into dystopia in the early 70s. In a possible attempt to cope with the macro-meltdown there is focus on the micro, on some shield from the atomization of society (one of the words Didion uses to depict the era) that is loosely associated with the family’s (Joan, her husband writer John Dunne, and their daughter Quintana) move back to New York.

A human and universal arc, under Dunne’s direction, effortlessly connects the dots between Didion’s work and life milestones. For anyone even remotely familiar with her essays and novels – where her theses are marked with immense precision along juxtaposing, negotiating and even contradicting dimensions – the eloquent silhouette of personal circumstances in “The Center Will Not Hold” is reason enough to watch.

Aesthetically, the film, like its protagonist, is of mesmerizing balance. It mixes scenes of a lost America with a recently interviewed Didion (82), by Dunne, at her respect-commanding yet comfortable Upper East Side apartment. It is a home that allows you to think clearly but does not let you get lost in the deep end; neither the sofas and cashmeres, nor the books behind (there are no surprises in the library) one up Didion.

The outdoors footage shadows Didion’s perceptive observations that have helped her connect illness with sky-colors and nuclear reactors (in “Blue Nights”), and, balance again, the cohabitation of her love and fear of nature. While we see a Hitchcock inspired ocean-looking cliff at Portuguese Bend, she voiceovers how her husband chaperoned her in swimming to a cave near their first home in California: “The tide had to be just right. And you had to be in the water at the very moment the tide changed. We had to be in the water the very moment the tide was right. Each time we did it I was afraid of missing the swell, hanging back, timing it wrong. He never was. You had to feel the swell change. You had to go with the change. He told me that.”

Naturally, the viewer can’t help but crave resolutions in a few of the endless Didion enigmas: insider vs outsider (or both, and how), strength vs vulnerability and, more important, or perhaps most debated, empathy vs detachment. Dunne, who in our discussion avoided the term documentary (he kept referring to his feature as a film or a movie), is the first to acknowledge that this is a family affair. A “love letter,” he told The New York Times. “If I was a more dispassionate, regular documentarian, there would be questions on the clipboard.”

Still, Dunne’s footage and interviews deliver insights. “I don’t know what ‘fall in love’ means,” Didion offers when she discusses her decision to marry John Dunne – Griffin’s uncle. “It’s not part of my world.” Or, “Maria [the famously detached main character in her novel “Play It as It Lays”] was quite a bit of myself,” Didion admits. “The day would start with John getting up and building a fire, and making breakfast for Quintana, and taking her to school. Then I would get up, have a Coca-Cola, and start work. Everybody had their own thing,” Didion demi-rationalizes a somewhat atomized family; this time her own. ‘It was not the way you think of Malibu. It was very out there… It was very Joan,” Amy Robinson, film producer and friend, comments as she describes the atmosphere at the Dunne-Didion Laurel Canyon-in-spirit-but-in-Malibu beach house.

Carefully, if not tenderly, Dunne gets in a few more personal questions. “What was it like to be a journalist in the room when you saw the little kid on acid?” Dunne asked his aunt – part of Didion’s coverage of the Haight-Ashbury hippie movement in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” the book of essays that made Didion a voice.

The first thing you register is that Didion replies with her hands. Not since Jessica Lange had someone used her hands more to speak on screen. The difference is that Lange’s hands turn inwards, towards her face, touching her mouth, giving her some cover or reassurance to complete an argument. Didion’s hands do the opposite. They reach out towards her audience; they bridge, complete her argument, aid in convincing, play with the dimmer-switch on the empathy vs detachment scale, and make up for any gap in her chosen words, or for words missing. They close the deal. “Let me tell you, it was gold,” she says, delivering her latest (already famous) quote. “That’s the long and the short of it is. You live for moments like this, if you are doing a piece.”

Her answer has already created controversy. Reviewers counted the seconds (seven) that it took her to speak, the spot where her eyes rested, the suggestion of a smile. There has been speculation of image-building, and criticism for her matter-of-fact, uncontextualized, unapologetic, I-was-there-doing-my-job response; without the so-others-can-do-theirs disclaimer. Maybe. But there is a footnote. What most viewers, and reviewers, failed to notice, or acknowledge, is a second pause (this time for three seconds) before she adds: “Good or bad.” This is her nod beyond the apparent setting.

Dunne tells me: “When she has a moment like: ‘that’s gold,’ yes, journalistically, that is. But it supports her thesis about the disillusion of families, the center not holding in American society, the death of the Eisenhower years, and going into what she saw before many others, a very dark time. That was written even before Bobby Kennedy was killed, when drugs were glamorized, and everybody thought about hippies, you know, they had their headbands, peace signs and everything was groovy. There is nobody out there writing like that. I think it is a great loss.”

The Haight-Ashbury child scene is so haunting that I cannot help but bring up an image of our own geopolitical disorder that turned the Aegean into a cemetery: Aylan Kurdi, the toddler whose body washed ashore on a Turkish beach. “That little boy on the beach, parallel image,” Dunne says, “A lot has been read about it, but there have been so many other terrible things, the little boy sitting from Syria, shell-shocked, there are images, but the outrage is so off the cuff, from the hip, that it dilutes the overall intent, you know, and it doesn’t have a lasting effect. A very common reaction has been a lament for the essay, for the deep thought, for the contemplative and the reflective train of thought about the world we live in. How many writers out there have written things from 50 years ago that people are still quoting today?”

Bob Silvers, the recently deceased head and founder of The New York Review of Books, who pushed Didion to cover international and domestic politics, found her “immensely knowledgeable, perceptive. A sharp observer.” Many of us learned to read what is behind a headline from Didion. I tell Dunne that this week, 10 years after the biggest financial meltdown, we are celebrating the launch of bitcoin derivatives (futures on a cryptocurrency not backed by any government whatsoever) as hedging opportunities, not as speculation. This same week, the pavements on Ninth Avenue in New York City were filled with tents, most of them occupied by paid line-sitters for the new $999 iPhone X. And just last week, a major Hollywood star responded to allegations of having sexually abused a 14-year-old, including: ‘and I choose now to live as a gay man.’ For the last one, I put my Didion hat on, and tell Dunne that – setting aside the lame and inappropriate association of homosexuality with pedophilia – he does not say: I am gay. Instead, he chooses now to live as a gay man. His words describe a choice. A lifestyle. Not an identity. Not homosexuality. Something almost political he is doing, something that perhaps he should be given credit for. I can see his aunt shredding this line to pieces.

Dunne: “Learning to read like that is really great, because when you learn to read you are learning that what The New York Times is saying is different from The New York Amsterdam News, in Harlem, you know, 50 blocks from where their headquarters are. The different messages, the different narratives, what politicians are trying to sell, and what they really mean, what their agenda is, and once you get into that rhythm of seeing how she sees the world, you cannot un-see it.”

See and un-see have been major paradigms in Didion’s work and life, and sorely soaked in heartbreaking irony. “We always had this theory that if you kept the snake in your eye line the snake wasn’t going to bite you,” Didion says in the film. Part of her interest in social, family, and personal disorder was a protection mechanism: “I, myself, have always found that if I examine something, it’s less scary.” Fair enough. But the snake finally bit Didion. Her daughter, Quintana, who fell dangerously ill right before Didion lost her husband, John Dunne, to heart failure, passed on a year and a half later, at age 39.

“As I was researching,” Dunne tells me, “I was really struck by something I hadn't been before, which was of the mother-daughter relationships that are consistent throughout her novels, and sometimes in her non-fiction, of a mother who has a very troubled daughter or a handicapped daughter, or a fugitive radicalized daughter, and that she had been running away, on a subconscious level, from the inevitable, as if, she says at some point, the cautionary tale. As if we have control over these things. She ended up writing, charting the disorder, the mayhem in other lives, and she is still with us, she is iconic, legendary and every one of those adjectives, because she did not spare herself when it was her time, she turned the lens on herself, to understand disorder and mayhem and grief. A remarkably brave thing to do.”

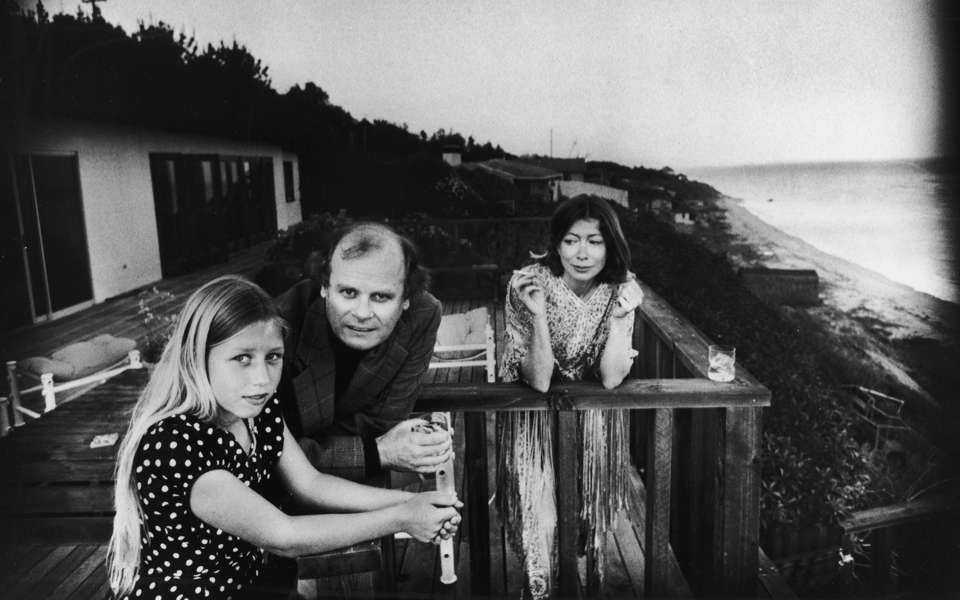

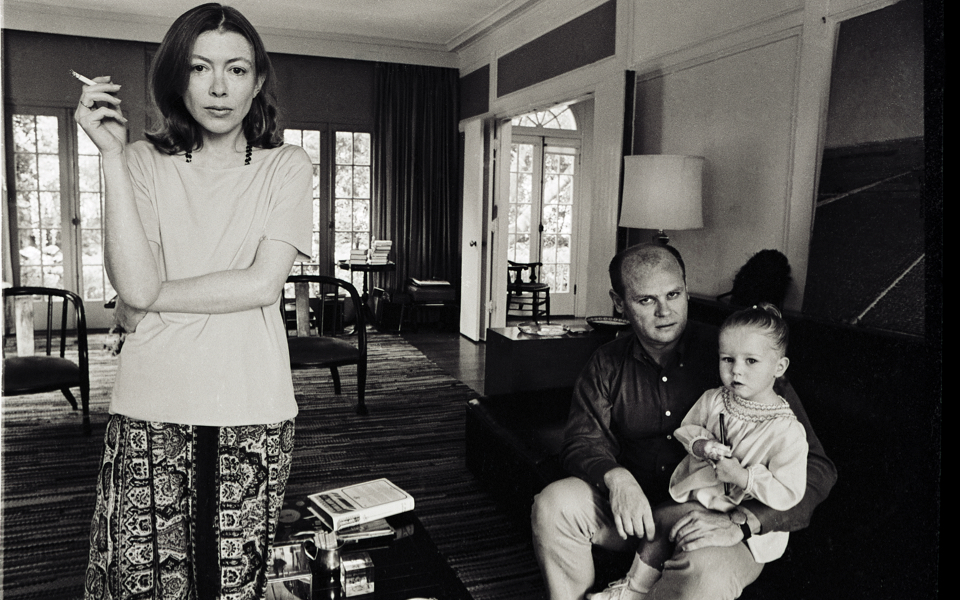

In “The Center Will Not Hold,” Didion discloses that Quintana found her “a little remote” as a mother. Didion was concerned about her daughter. What was it you were concerned about? Dunne asks her in the film. “I was concerned because she was drinking too much. That was… the first concern.” What about the rest? There has been criticism of little straight questioning from Dunne to Didion here. Correct and largely expected. But look carefully, and Dunne has allowed footage and interviews (albeit with friends) to do some revealing of the footsteps there. Friends remember Didion coming to her kitchen in the mornings with dark glasses on – no talking. In two of the most seminal photos of the family, one in their living room, the other on the patio, one can easily detect a body language gravitational division between Didion, on one side, and John and Quintana, on the other. During his interview, writer Calvin Trillin says, “Among all the married couples I knew, they were the ones who were almost always together.” This was a Reagan-couple signature trait. Under the cautionary tale prism, and again ironically, Didion crossed swords with Nancy Reagan (someone portrayed as a distant and contentious mother by her daughter) when Didion described the Reagans’ abode in “The White Album,” “it is the kind of house that has a wet bar in the living room,” wrote Didion in 1977. Such associations can cast some skepticism on the cautionary tale position: Could Didion have been picking up some familiar weaknesses in her subjects?

John and Joan had clout, and so did Griffin’s father, Dominick Dunne (John’s brother), who was a film producer, journalist and author of many books. I ask Griffin how did he survive (thrive really) in that era, with the weight of the generation just before him? “I thought about that a lot,” Dunne says, “and I’ve always believed that one generation has a very powerful impact on the future of the next, either negative or positive. And then some of it of course is just genetics. I grew up in a household that, you know, the parents were very very unhappy and pretended they weren’t, so there was a great deal of pretense, that was shaken with their divorce, but the true tragedy was, you know, they lost their daughter, my sister. Particularly on the Dunne side there was suicide and plane crashes, and a world of woe. John and Joan were always there the next morning, to offer their support, to whose ever family had been affected. And they were there, they didn’t leave. They would do the groundwork to make sure who would be invited to [the funeral], who knew about the death, what the funeral was, who would do it. They would always be with Quintana and I remember thinking: Well, tragedy is never going to touch them. I didn’t mean that in an envious way but they just struck me like, well, they are going to be spared all this. Because, you know, if so much had happened in their immediate nuclear families around them, that the odds are so much in their favor. And, well, I could not have been more wrong.”

With Dunne’s prompt, Didion recognizes that writing “Blue Nights” (the book she wrote about her daughter Quintana, after she died) was quite a different experience creatively, but she stops there. It is up to Dunne’s editing and ordering of the remaining scenes and quotes to suggest some insight on why “she did not spare herself when it was her time, she turned the lens on herself.” The two most potent lines that Dunne chooses for the end of the film are: “Yet there is no day in her life that I still do not see her” (from a prose poem in “Blue Nights”) and, the very last line, “Remember what it is to be me, that is always the point.” This order turns the film’s arc into a circle. “Remember what it is to be me, that is always the point” is the portal that takes the viewer back to the John Wayne America, to a character era, not a personality era (John was the personality, Joan the character), and to an early piece she wrote for Vogue about self-respect during her first job. I tell Dunne that thanks to his film, years from now, people may understand Didion better through that pivotal piece at Vogue, of all the places she worked.

Dunne: “‘On Self-Respect,’ that essay, is in there because, as you know, it came under deadline, she came up, and just pulled an all-nighter, and wrote how to live with yourself. By a 23-year-old. And why it’s there, and why it fascinates me is that the woman, the girl who wrote that is the same woman whom I interviewed. That essay, that work ethic, taking responsibility, not taking short cuts in life, diving into the things that are painful to look at in yourself, or at the world around you, the girl who wrote that is the woman, has not changed at all. That is very interesting to me. She is fortunate to have a perspective and a survival with a self-reliance to know that her writing will keep her sane. She doesn’t write for results; she doesn’t write for ‘this is a book that will bring comfort to others as well,’ or ‘this is in my canon of work,’ or any of that. But I think she knows enough about herself, I think she understands her own character, I think she understands her own strength, and if she has weaknesses I think she has the strength to write about them and make them public.”

* Ioannis Pappos is a management consultant and writer from Pilio, central Greece. He is a graduate of the National Technical University of Athens, Stanford University, and INSEAD Business School, and has worked in both the US and Europe. Pappos contributes to papers and magazines, and is the author of the novel “Hotel Living” (finalist for Lambda and Edmund White Debut Fiction awards). He lives in New York City.