The Greek capital in the 1960s as seen by an expectant American

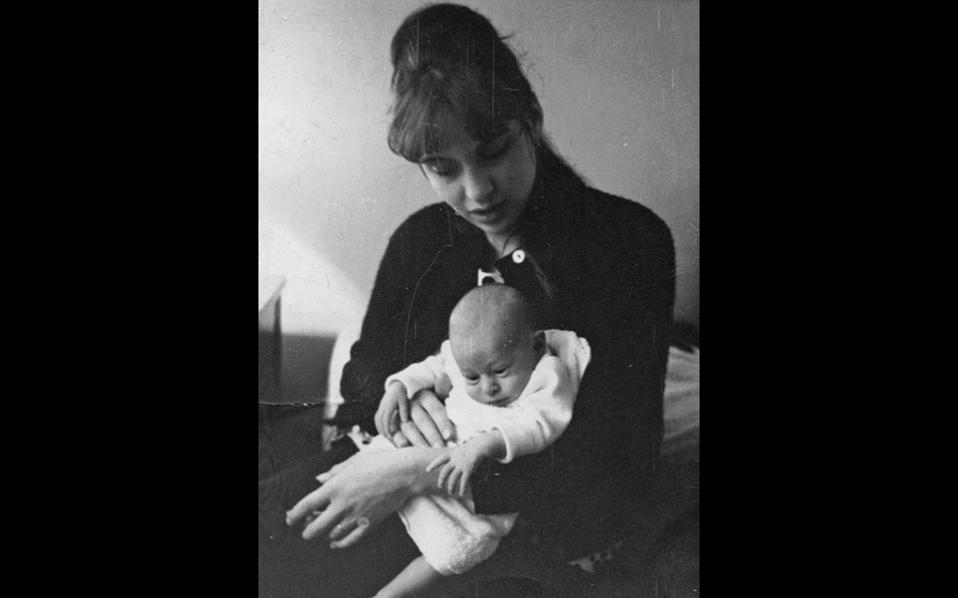

I was personally swept away by how that beautiful, bright and charismatic American saw Athens back in 1964, when she had her son in downtown Exarchia. While it reads like a fairy tale, there is nothing fictional about the story told by Frances Karlen Santamaria (1937-2013) in “A Room in Athens: A Memoir,” a book that is both old and new at the same time, and has been published in its English original on the initiative of her son, writer and journalist Josh Karlen.

Josh was still a baby when the family left for New York and although he never came back to Greece again he did grow up hearing the slightly exotic, paradoxical and charming story surrounding his birth. “A Room in Athens” is basically his mother’s journal, but it is also so much more than a simple record of events; it is a tale of awakening and fresh comprehension.

It could be a tale of labor, of the natural childbirth experience that Frances sought in Athens in 1964 at Madame Kladaki’s Psychoprophylactic Maternity Home at 26 Bouboulinas Street, behind the National Archaeological Museum. It could be the tale of an intellectual who boarded a Yugoslav freighter in New York along with her husband, a columnist for Holiday magazine, and set off for the Old World as a young couple both aged 26, sailing to Morocco, Spain, Wales, Denmark, Germany, Yugoslavia and Greece. It could also be the tale of a journey of self-awareness in the Cold War era in a geographical circle stretching from Tangiers to Athens, via the heart of Europe. But none of this would stand alone if it weren’t for the depth and curiosity that Frances displays in “A Room in Athens” and makes it a both quirky and authentic look at the Greek capital in the 60s but also a study of this charming woman’s personality.

“My mother had an fine natural intelligence and insatiable curiosity, combined with a first-rate education at Antioch College,” Josh wrote in the book’s introduction. “In Athens, my mother was pregnant both with her first child and with her book; each day, both grew and matured seemingly all on their own.”

The book was initially published in the United States in 1970 under the title “Joshua, Firstborn,” but a new release bears the title that Frances herself had wanted.

It fell into my hands after I received a message from Josh, who was looking for help in cross-checking some of the elements mentioned in the book. His mother’s time in Athens was not just as a temporary resident, but also as a social anthropologist. The event that Josh was most interested in exploring was his birth. Haris Kladaki, referred to in the book as Madame Kladaki, was a gynecologist who ran a private clinic that was very popular among the city’s middle-class women, though shunned by the medical establishment, which disapproved of her views on natural and painless childbirth.

There was very little to learn from the internet, but the surname did lead me to Petros Kladakis, the owner of the Orloff Hotel on the island of Hydra.

“The midwife Haris Kladaki was my father’s sister,” he said when I contacted him. “My aunt was the first in Greece to introduce the Lamaze method to Greece, which she applied with enormous success throughout her career. Unfortunately, she did not leave an heir and was vehemently fought by modern doctors, who are obsessed with cesareans.”

Frances’s description of her experience at the clinic is also fascinating from a sociological perspective, as she often conversed with other pregnant women and their families. Her observations of middle-class Athenians women and their huge family circles are delightful, as Frances allowed herself to write what she felt, without the kind of critical tone that often creeps into such narratives.

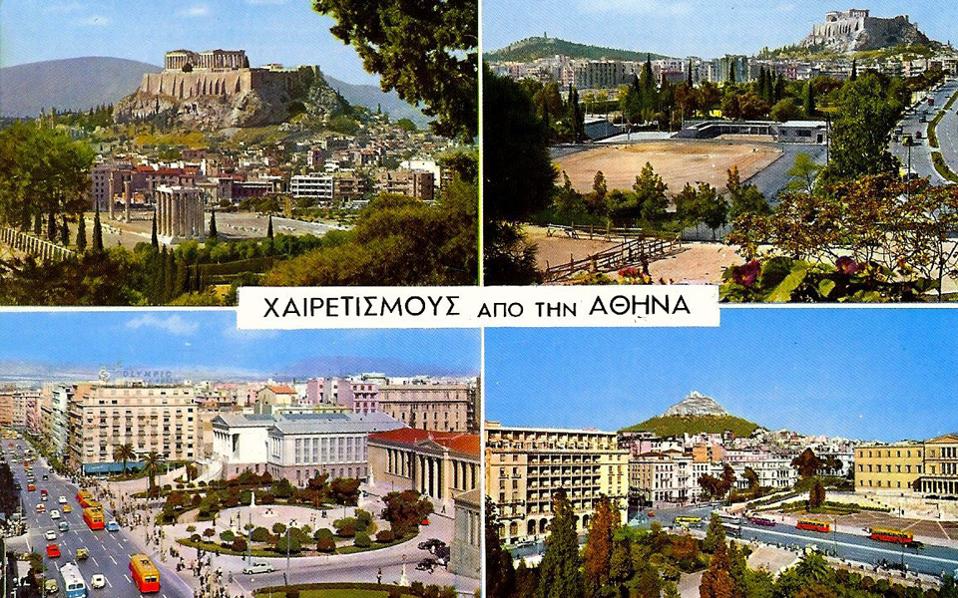

Athens was a city in flux in the 1960s, full of contrasts that were not just evident in the new buildings mushrooming all over the capital but also in the mentality of its residents.

“The Athens that confronted my parents when they drove south from the rugged villages of Yugoslavia was modern, flashy, crowded, and polluted,” wrote Josh. After some trials and tribulations, the couple settled into an apartment at 12 Karneadou Street in the upscale Kolonaki district.

“As modern as Athens appeared, it lacked much that was taken for granted in America, such as television and supermarkets.”

Frances’s acquaintance with the neighborhood and everyday Greeks, whom she describes as “the most beautiful people we had seen in Europe,” has resulted in sharp yet fair descriptions.

Josh conceded that in some parts, Frances’s comments on the Greek culture may seem like “uncharitable swipes,” but justifies the observation by explaining her mind-set at the time. After all, a love for Greece had brought Frances all the way across the Atlantic and Europe, along with other modern Philhellenes drawn to the country by “Byron, Miller, Durrell, bouzouki music, and films.”

“I had carted my unborn child halfway around the world to be born in the crux, the omphalos,” wrote Frances.