The enigmatic philhellene, Mr Perilla

The wondrous work of the French art historian, painter, photographer, traveler, typographer and writer who fell in love with Greece

The history of art is full of unsung heroes. Their names have remained in the dark, either because we turned our backs on them or because they chose to. We only find them hidden in archives, libraries, rare old editions and on dusty shelves. Even in the age of the internet, where one would expect all human knowledge to take its place in well-organized, global digital catalogues, those artists manage to slip the light, as if their mystery should remain eternal. One of these artists is the French painter Francois Perilla, who came to Greece in the 1920s and eventually made it his second home. His personal life is a mystery. We know he was born in 1874, but not when and where he died, while even his name is written in various ways – Francois, Francesco, or Francisco. His memory lives on through a series of (now-hard-to-find) books that he wrote and designed that include the content of his tours around the country.

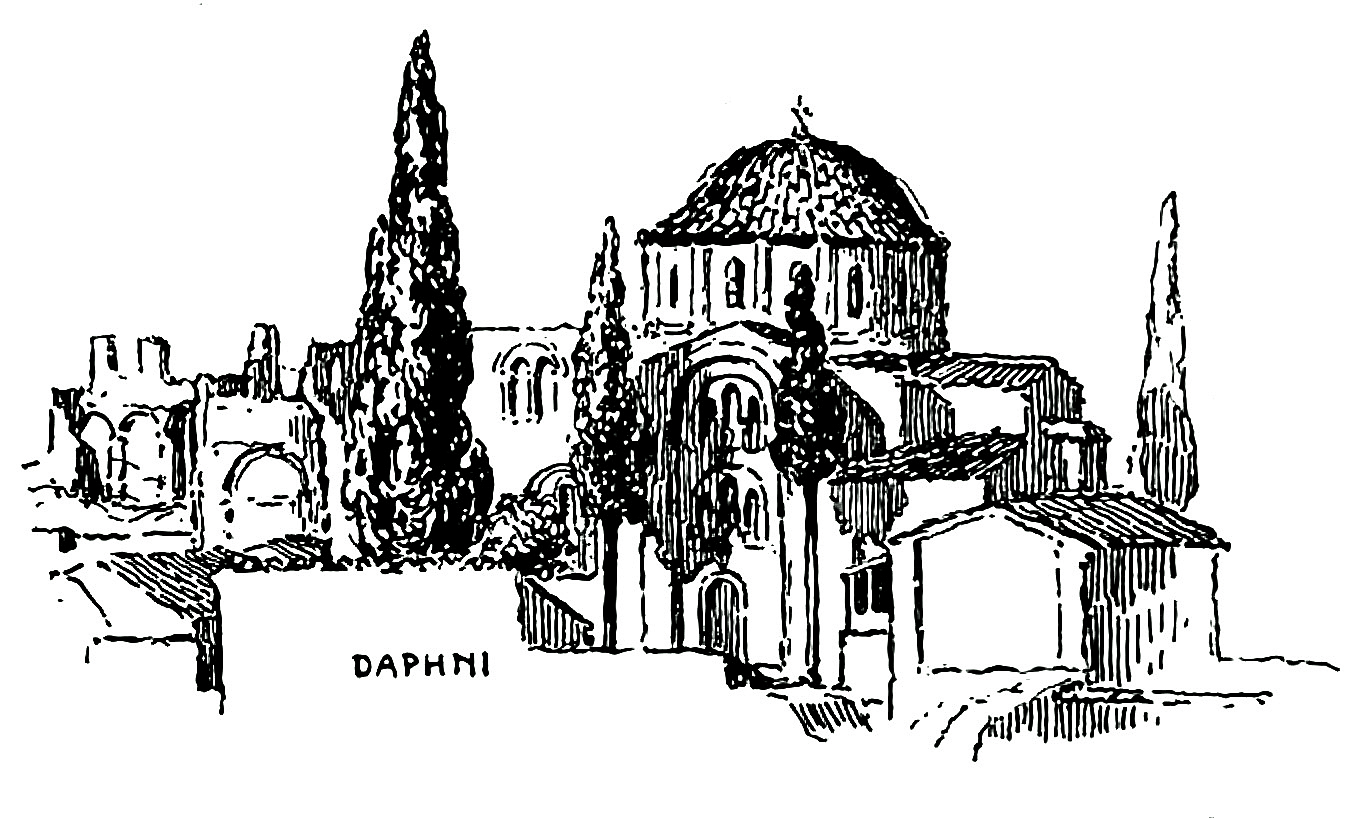

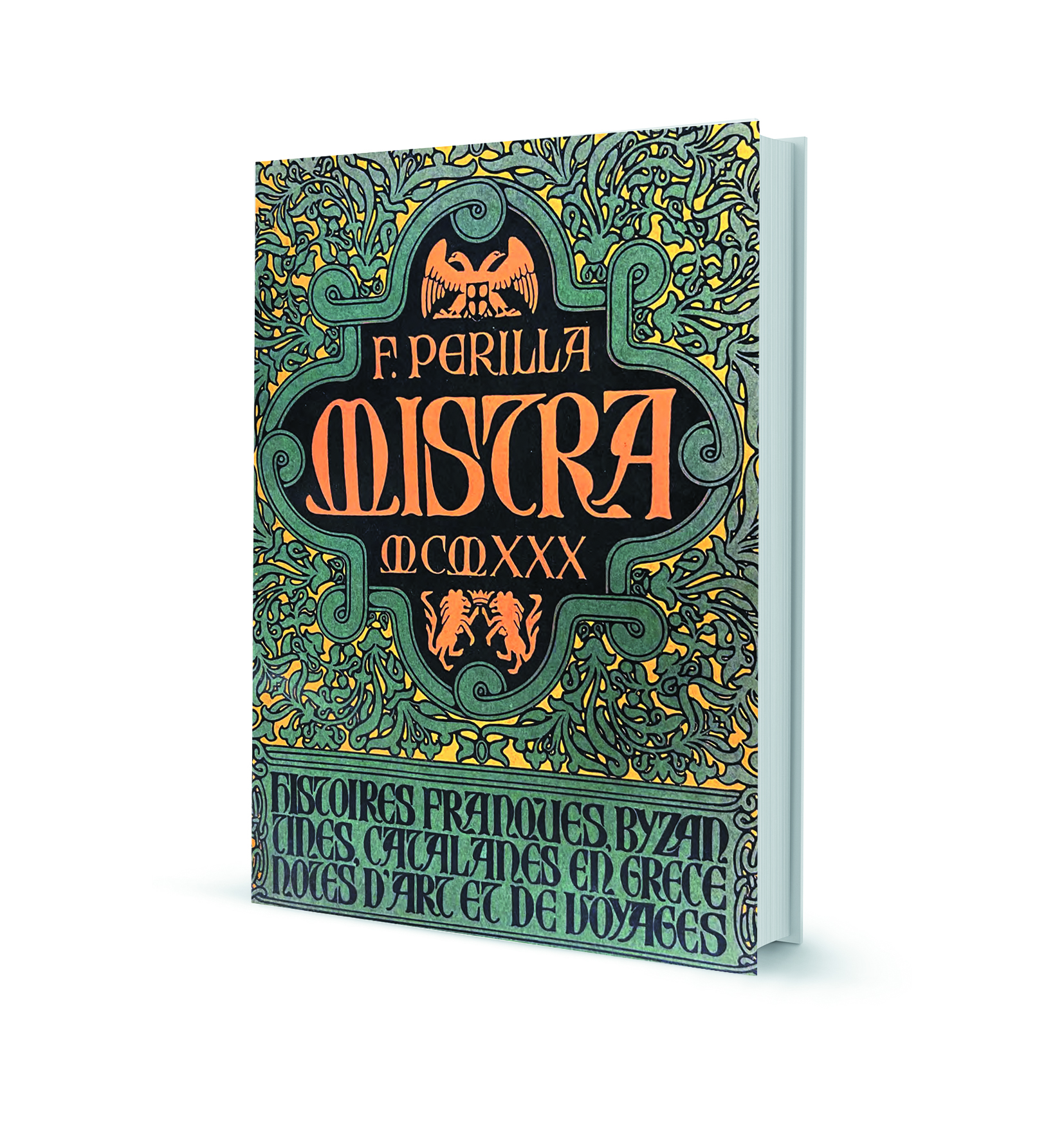

We are lucky enough to hold in our hands one of those books, “Mistra” (full title in French original: “Mistra : Histoires franques, byzantines, catalanes en Grece, notes d’art et de voyages. Dessins, aquarelles, photographies de l’auteur,” Athens, Editions Perilla), published in 1929. The book is a travel diary of a long tour in the Peloponnese but also in Central Greece and Attica, including Athens. Written in French, it is set in wide single columns which, while one might expect them to tire the eye, they never do, since they are supplemented with black and white sketches, afterimages of the landscapes encountered by the traveler which recall a pre-war forerunner of modern comic books. Combined with the unexpected, playful typography and sparkling descriptions, the reading experience of “Mistra” has none of the medieval gravity of the Byzantine monasteries and Venetian castles it refers to.

We are lucky enough to hold in our hands one of those books, “Mistra” (full title in French original: “Mistra : Histoires franques, byzantines, catalanes en Grece, notes d’art et de voyages. Dessins, aquarelles, photographies de l’auteur,” Athens, Editions Perilla), published in 1929. The book is a travel diary of a long tour in the Peloponnese but also in Central Greece and Attica, including Athens. Written in French, it is set in wide single columns which, while one might expect them to tire the eye, they never do, since they are supplemented with black and white sketches, afterimages of the landscapes encountered by the traveler which recall a pre-war forerunner of modern comic books. Combined with the unexpected, playful typography and sparkling descriptions, the reading experience of “Mistra” has none of the medieval gravity of the Byzantine monasteries and Venetian castles it refers to.

In this black-and-white world of letters, sketches and black ink, colorful watercolors and sepia photographs are rhythmically interspersed, precious testimonies of a long-lost Greece. In the book, priests, shepherds and villagers dressed in their traditional costumes all look like they sprung from the pages of the Greek Revolution of 1821. In two of these photos, a shepherd from Sparta has a touching innocence in his gaze. The same purity is found in the landscapes caught in the photographs – from the cliffs above the waves of the Mani Peninsula to the inner courtyards of the monasteries at noon. In these images we encounter a world that no longer exists.

As incredible as this may seem, texts, sketches, watercolors, photographs, graphic editing and the publication itself, all bear the signature of Perilla. Perhaps only one of his Greek colleagues – and in fact his contemporary – had such a versatile talent – the great illustrator Nikos Kastanakis. With this powerful, creative arsenal, Perilla traveled all over Greece, from the Cyclades and Chios to Delphi and Mount Athos, capturing in a complete creative package the “spirit of the land,” not with a colonialist gaze and detachment but with love, closeness and understanding.

ELPA’s road maps

Looking in the few available sources, we find some more traces of him. We discover that the then-new and active Automobile and Touring Club of Greece (ELPA), a Greek motor sports organization which closed in 2019, had printed road maps with Perilla’s designs, while in December 1930 ELPA organized an exhibition of his works, and the newspaper Eleftheros Anthropos (Greek for “Free Man”) had announced the fact as follows: “In the halls of ELPA, on Kanari and Merlin streets, the exhibition of the works of the foreign artist, who exclusively exhibits Greek landscapes of Mystras, Chios, Skyros and the Peloponnese, opened the day before yesterday.”

Perilla often designed for other publications besides his own, as in the case of the novels “The Commander” (original title “Der Commandant,” 1933) by Swiss writer John Knittel (originally Hermann Emanuel Knittel) and “Theatre” (1937) by British writer W. Somerset Maugham, published in Greece by Fili tou Vivliou, for which he designed the covers. Furthermore, the book he published in 1949 about the Greek Revolution and the merchant, military officer, politician and author Yannis Makriyannis (original French title “Fragments de la vie heroique de Makryjannis suivis des ses images de l’epoque grecque”) received praise in the same year at the 12th Book Exhibition organized by the Society of Artists. The cover he designed for that edition is a true “tour de force” – but that was the case with every cover he made, as well as with “Mistra.” The hand-crafted letters and patterns of exquisite detail, the skillful management of information and space, the use of Latin dates and cryptic symbols set up a visual celebration that would be the envy of modern graphic design.

The mysterious artist had, in his time, acquired a fanatical following. He was praised by the master of travel literature and acclaimed poet and journalist Kostas Ouranis, who wrote in 1932 in the Elefthero Vima newspaper a laudatory review of Perilla’s book about Macedonia, titled “Across Macedonia” (original title in French “A travers la Macedoine,” 1932). The literature critic and litterateur Cleon Paraschos also wrote about him lovingly in 1940 in Nea Estia, in a review of his book about Mount Pelion, “In the Land of the Centaurs” (original title “Au pays de Centaures-Le Pelion,” 1940). Paraschos describes him as “a well-traveled man and a friend of travel,” “a warm admirer and connoisseur of Greece” and “cultivated, sensitive and gifted, with an eye and a memory for painting,” while emphasizing something that also characterizes the text of “Mistra”: the simplicity of the narration, which, as he says, makes us live the life of that place “not lyrically or poetically, but close to its everyday reality.”

Indeed, reading in “Mistra” a passage from his visit to Athens and Piraeus, it is as if we are going back in time and reliving the everyday life of those times: “Piraeus is the port of Athens, towards which the capital is rapidly spreading its tentacles along the electric rails, where before long houses and factories will hide this broad, dusty Attic ribbon. In a smoky atmosphere, a forest of masts and smokestacks prepares for a more arduous tomorrow and the creation of a larger port. Alleys and great [road] arteries, shacks and palaces, steamships and ocean liners, carriages and limousines – they all make a great commercial and naval Babel.”

‘As necessary as bread’

It is also interesting how he describes the Athenians as avid newspaper readers, during the train journey from Piraeus to the center of Athens: “In the 20 minutes of the journey, everyone is reading a newspaper. It is unbelievable how many newspapers are printed in Greece! And all of them are well made, presentable, in large formats and with a variety of titles. Everyone here reads with such frenzy, that they say that the newspaper is a commodity as necessary as bread!” An insightful folklorist, a sophisticated and tireless traveler and an artist gifted with a multifaceted and heaven-sent gift, Francois Perilla came quietly, like a luminous apostle, and left just as quietly. The about 30 publishing gems he left behind glorify graphic arts and exemplify in the most impressive way their high potential, while representing for our country an unknown visual treasure and a priceless legacy of culture.