Renowned academic offers glimpses into her storied life

One day, when she was a professor at the Sorbonne, she brought the wrong briefcase and walked into a sophomore class with teaching material for postgraduate students. She had to teach the class without any notes. She actually liked it a lot. “You had to remember a lot,” her students noted enthusiastically. “Yes, from my mind’s pool,” she said. “This ‘pool’ is my autobiography,” says 94-year-old Helene Glykatzi-Ahrweiler, days before the publication of her book “600 Pencils and 10 Poems” by Govostis Publications: 192 pages with fragments from the renowned Byzantinologist and first female rector of the Sorbonne’s life, from her childhood in the Athens neighborhood of Vyronas to international recognition – as narrated to journalist Anna Grimani. The book’s core is her 2006 biography (which has long since gone out of print), to which she added some new short stories, 10 poems and never-before-seen photographic material.

Why “600 Pencils”? When she was in elementary school, she envied the pencils of a classmate. “Today I have over 600 of them! Boxes and boxes full of pencils. Not to mention the number of books,” she says.

For Glykatzi-Ahrweiler, the most immoral act is the lack of self-consciousness. She conquered it with great difficulty. What is this book but a journey in self-consciousness? “I owe what I am now to the Occupation and the Resistance. I have put all of my fears… as if I wear a uniform. Which one? The discipline one, I think. To prevent anyone from seeing them, even my husband, my daughter, or my colleagues. To stand in front of my fears without letting them take control. Who can believe I have so many fears?” says the woman who made Byzantium accessible to Greeks of all ages. And she tells us of her extraordinary life.

Formative years

“Ι was born at 21 Kolokotroni Street. At that time, of course, it was called League of Nations Street, then Ioannou Metaxa and then Kolokotroni again. This, to me, is the synopsis of the historical destiny of the peoples, who change regimes, allies and even their own history.” The Vyronas house had no heating. But it was loud – with six kids eating at the same table and sharing one room.

The Glykatzi family is captured in a photograph with all six siblings and their mother.

She learned how to read and write before going to school, by observing her siblings. Especially her older brother whose nickname was “the Count of Monte Cristo,” because he was very elegant. The books she got afterward she kept for herself, so she could make them her own. “My mother had a seamstress in Filolaou Street, which was in the countryside back then, and as we were going there one day, as all windows were open because the weather was so nice – what an image! – I saw a library in a house. I climbed the small wall up to the windowsill, stood on my toes to admire the first library I ever saw – what a beautiful thing.”

She was ranked 13th in the university entrance exams – “fortunately in 1945, we could pass these exams without a certificate of political convictions” (her decisive action in the Resistance goes back to her childhood where she was known to everybody as “the blue-eyed girl”). “I grew up on the street – in the big world. For real! In a refugee’s house, but with the company of the Acropolis. Can you imagine what it meant?” She was an excellent student, she smoked nonstop and read a lot. In one class, a professor of Classical archaeology told her: “Look, Glykatzi, not everyone here needs to work; but you do. Why are you here and not in the Literature Department?” Woman could not go into the Archaeological Service at the time. She answered: “Look, Professor, in this life, I will do what I like and what I want. Now, about me earning my life, I assure you that I will sell lemons in the center of Athens.”

She hung out with the boys from the Philosophy and Law departments and the 10 girls of the Archaeological Department. Helene had a chessboard and in their free time they played nonstop. In the evenings, the games continued on the rocks of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, during the intermission periods.

The girls were regulars at the city’s Rex Theater, where they ordered milkshakes. “Guys, I have no money. I’m not coming,” she always said. “It’s on us!” the other girls would shout. “On whom? I must know,” she responded, but at some point she could not go anymore, until her older brother, who had gotten a job, gave her some money. “I started to order vermouth, it was the cheapest on the list.”

Helene and her husband Jacques Ahrweiler, who she married in 1958.

Among the French friends who gathered in the beautiful home of writer and diplomat Armand Meggle was the French Army officer Jacques Ahrweiler. He didn’t speak much and, when she described him later, she said that his behavior and knowledge made her think that he was one of the young intellectual writers of the circle. They met again when Queen Elizabeth II took a cruise on the Seine and those who had a house with a balcony on the river invited friends to see the spectacle. Jacques was already separated from his first wife and lived at the Bucherie, an upscale hotel opposite Notre Dame. His closest friends were the poets Claude Roy, Paul Eluard and Louis Aragon and the novelist Elsa Triolet – who were inseparable – and the writer Simone de Beauvoir.

Glykatzi was on the staff of news magazine Le Nouvel Observateur, with Patrick Kessel, Francoise Verny and Roger Paret – at a time when the war in Hungary had divided French intellectuals. In another group of friends was the young Francoise Sagan, who had just published “Bonjour Tristesse,” and Gaby Aghion, founder of the French fashion house Chloe, among whose discoveries was the young Karl Lagerfeld.

Marriage, family and academia

Jacques was from a bourgeois Parisian family and was studying physics and chemistry. His closest friend was the writer Jose Bergamin, the godfather of Florence Malraux and close friend of Pablo Picasso. Jacques’ first wife, Alice, was the translator of Pablo Neruda into French, and was married to the Goncourt prize winner Pierre Gascar.

Every Tuesday evening, Helene, Jacques and Bergamin would dine at the Lipp in Saint Germain des Pres. That particular night, it was snowing. When the time came for them to leave and Jacques to accompany her home and then return to the Bucherie, Bergamin told them: “I don’t get you… You go separate ways when it is so cold outside. Why don’t you get married?” They had been together for two years – it was the beginning of 1958.

On their first trip to Greece, Jacques and Helene crossed Yugoslavia by car. “They stopped us in Skopje, because I was born in Athens – wild thing. Then we followed a stranger’s car, so as not to get lost, and when we arrived in Thessaloniki, I asked Jacques to stay one day, to visit my godmother.” During their visit, Helene’s godmother, as the tradition of her homeland Asia Minor dictated, served glasses of cold water and spoon sweets in a big bowl with teaspoons – from which you were supposed to take one spoonful just for the taste – but Jacques, who didn’t know that, wanted to be polite, and ate almost the whole bowl. “You should have told me that. I have to know the traditions,” he kept telling her after Helene explained to him later on.

Her thesis was on Byzantium and the sea. She submitted it on April 10, 1964. She was already nine months pregnant. On the same afternoon she and Jacques went for a walk, ate ice cream at Montparnasse, and the next day, April 11, she gave birth to Marie-Helene. A few months earlier, her nanny, Fotini, who was from Asia Minor and had raised her and her brothers, had arrived in Paris, on the condition that she would leave after 10 years. She asked to watch TV regularly, to begin to understand the language. While doing so she would hold the baby on her lap. When Marie-Helene grew up she hated TV. Fotini was always close to the child, from the gardens of Paris to the estate of Grandma Ahrweiler in the countryside. Her care for Helene and Jacques was exemplary.

Her thesis was on Byzantium and the sea. She submitted it on April 10, 1964. She was already nine months pregnant. On the same afternoon she and Jacques went for a walk, ate ice cream at Montparnasse, and the next day, April 11, she gave birth to Marie-Helene. A few months earlier, her nanny, Fotini, who was from Asia Minor and had raised her and her brothers, had arrived in Paris, on the condition that she would leave after 10 years. She asked to watch TV regularly, to begin to understand the language. While doing so she would hold the baby on her lap. When Marie-Helene grew up she hated TV. Fotini was always close to the child, from the gardens of Paris to the estate of Grandma Ahrweiler in the countryside. Her care for Helene and Jacques was exemplary.

She became a teacher at the Sorbonne in 1967. “Paul Lemerle had decided to go to the College de France, so he was leaving his post, and I was the only one to have my thesis printed. We were three candidates. We had to have 126 meetings with the professors. When I went to see Henri Van Effenterre, the great Hellenist, he told me, ‘Helene, I will not vote for you, but for my friend [Jacques] Bompaire, who is French and rector at Brest.’ So did Jacqueline de Romilly, even though we were supposed to be friends. ‘We are too many women,’ she told me. Then I went to the Spanish professor, and before I even opened my mouth, he told me, ‘I will vote for you.’ ‘Why?’ I asked him. ‘Because we have the same accent!’ Then it was the turn of the most far-right professor, and before I even got to his office, I thought to myself, ‘It is meaningless.’ He told me, ‘I know you don’t belong to my circle, but I will vote for you.’ ‘Why?’ ‘Simply because you have published so many texts and epigraphs, you have a diplomatic history, you cover the whole field of auxiliary sciences and basic history.’”

Her first concern as soon as she was appointed was to meet her prospective students. “Folks, I came to see what we will do this year. I am your professor of Byzantine history,” she told them. They looked at her in disbelief.

Her first concern as soon as she was appointed was to meet her prospective students. “Folks, I came to see what we will do this year. I am your professor of Byzantine history,” she told them. They looked at her in disbelief.

“I was young then, beautiful; they also heard my accent. ‘She must be some crazy girl,’ they might have thought. I realized that they did not believe me. ‘Come to my office. Let’s talk there,’ I insisted. After a while, five smiling faces came – I opened the door for them, they were a little embarrassed. They sat down, we discussed the issues that concerned them and when they left they showed due respect. A week later, we had a meeting. The dean asked me, ‘Mrs Ahrweiler, did you go and see the students?’ My friend and colleague Bernard Guenee, the great academic, elbowed me: ‘Helene, we do not say good morning here, except to the lecturers. Only assistants teach the freshmen, the professors teach the postgraduates.’ Well, one year later, we had the events of May 1968. You understand why.”

Receiving the Gold Cross of the Legion of Honor from President Francois Mitterrand.

When she became rector of the Academy of Paris and chancellor of the Universities of Paris, she applied a personal principle: “I never send my secretaries or assistants to a superior. I’m always first in line, with a frank face, as my father used to say to me.” She started classes quite early – three times a week, she was at the office at eight o’clock in the morning, and dealt with all the administrative issues afterward. She and Jacques made sure to meet at home at noon every day, to see Marie-Helene and to be together for a while. Then, she worked again until the evening, when the cycle of social obligations began. She never went to bed after midnight.

Artichoke stew

When she had guests at home, she cooked her own recipes, with her artichoke stew becoming a favorite. “It became a trend in most French homes,” she says. Every time her mother came to Paris she brought her recipes: for sweet bread, roast quince, honey Christmas cookies.

“Of course, I never just followed a recipe, because I think that good cuisine is both a matter of imagination and good heart. I have the imagination, my husband has the good heart! However, I feel very emotional when I look at the recipes in a notebook handwritten by my aunts, my grandmother and my mother. I also write every new recipe there.”

‘No’ to Skopje

In 1983, just after Josip Broz Tito, the leader of Yugoslavia, had passed away, Francois Mitterrand traveled to Belgrade, accompanied by photographer Francois-Marie Banier, Foreign Minister Claude Cheysson, political adviser Jacques Attali and Helene Glykatzi-Ahrweiler, who would sign agreements with universities there. “As we were eating, the Yugoslav foreign minister sitting next to me was talking to Cheysson, and Cheysson turned to Mitterrand said: ‘Mr President, have you heard what my colleague is saying, that the Macedonians are like the Palestinians and the Greeks like the Israelis? They expelled them, they took their lands, they took everything and we have to do something for them.’ Mitterrand looked at me – they did not know I was Greek – and I nodded to him, ‘No, it is not like that.’ And he answered immediately: ‘Don’t worry, Cheysson.’ A few days later, on the same trip, I was offered an honorary doctorate by the University of Skopje. I said, ‘No thanks.’ ‘Why not?’ they asked. ‘I am an honorary doctor of the University of Belgrade,’ I replied, ‘and I believe that Belgrade covers for the whole of Yugoslavia.’”

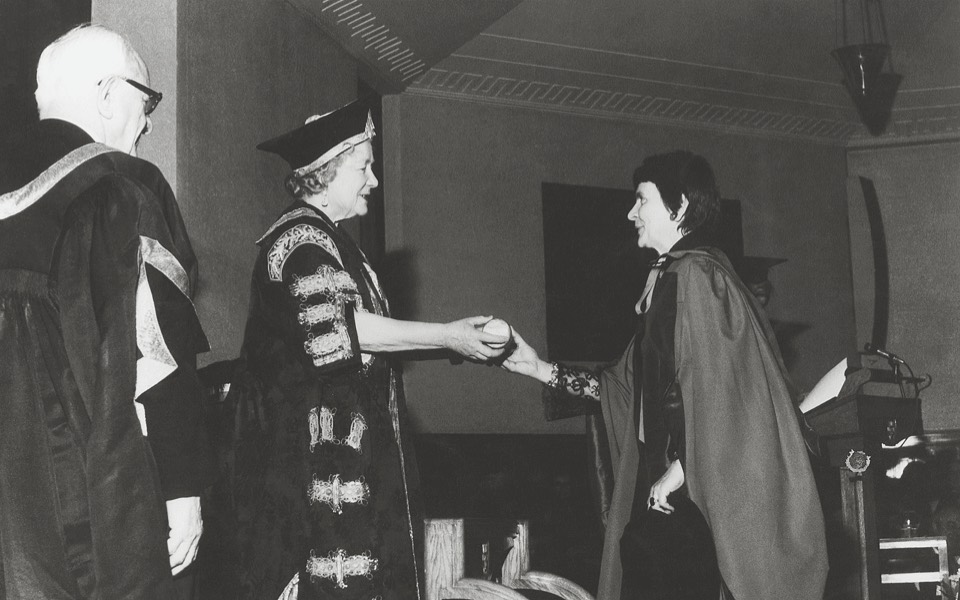

Accepting a University of London honorary doctorate from the Queen Mother.

She was rector of the Academy of Paris when Yiannis Latsis called her. “Give me your number and I will call you back,” she told him. He was unpleasantly surprised, but, when she called him, she explained: “Anyone can tell me, ‘This is Mr Latsis speaking.’ Now I’m listening. What do you want to tell me?” “I want to establish a university in Athens. I will spend all the money needed. I will buy, say, the Tatoi royal estate, to build it there,” he replied. “I’m sorry, Mr Latsis. You cannot do that, because a university, both in Greece and in France, is a public institution. So, you are not allowed to grant university degrees. You can establish an institute, but not a university.”

That conversation, with the insight of Yiannis Latsis, became an occasion for them to meet in person. “Captain,” she told him once, several years later, when the Skopje issue was in the news, “why don’t you buy Skopje to put an end to all this?” And he replied, “It’s not that it’s expensive, but it’s no longer on the market; it has been sold to someone else.”

Helene Glykatzi-Ahrweiler became friends with Erietta Latsis who one day introduced her to two doctors of Yiannis Latsis. “You will meet a friend of mine who is richer than me.” They looked at her in surprise. “What are you telling them, Erietta?” “I am telling them the truth. You will never lose what you have, while me? I may lose what I have at any point.”

Friendship with Karamanlis

Helene Glykatzi-Ahrweiler met the Greek statesman Konstantinos Karamanlis via his close friend Fofy Leventis, who was founder and director of the Centre Culturel Hellenique, of which Helene Glykatzi-Ahrweiler was the honorary president at that time.

“I have one word for him: Doric! I think he showed a lot of confidence in me. How many times didn’t he call me in Paris to ask, ‘What do you think about that?’ He wanted my opinion. We had lunches together. We never discussed politics; he only said to me once: ‘Tell me, what’s with all of them and Macedonia? I am a Macedonian, I am the president of the Republic, did I even speak? Why are they talking?’ The image I have of Konstantinos Karamanlis is that of absolute seriousness, of the last great Greek politician, together with Andreas Papandreou; but he was more modern, he had a different spirit. I would compare Karamanlis with de Gaulle; Andreas with Mitterrand, whom I consider to be one of the great politicians, and an innovator.”

They met often, they had established a relationship based on excellent communication. Claude Pompidou, a friend of hers, invited them to her house. For the French, Karamanlis has always been a head of state. As they were having dinner one night, she told them, “As far as I am concerned, I approve of Karamanlis from 1974 and on.” And he replied, “Helene, don’t pretend to be a communist.”